Reading Choices: Realism, Truth, And The Bible

Without intending to, Friday’s SpecFaith guest, James Somers has re-introduced one of the controversies surrounding Christian speculative fiction. James made the point in his article, “How Then Can It Be Christian?” that the Bible itself addresses evil in all sorts of guises, so certainly our speculative fiction can do the same.

Without intending to, Friday’s SpecFaith guest, James Somers has re-introduced one of the controversies surrounding Christian speculative fiction. James made the point in his article, “How Then Can It Be Christian?” that the Bible itself addresses evil in all sorts of guises, so certainly our speculative fiction can do the same.

However, he outlined parameters for our stories:

While we do have freedom to explore many avenues, we should never find ourselves compromising Godâs Word or his person . . . we should never present a view of the world that contradicts Godâs Word.

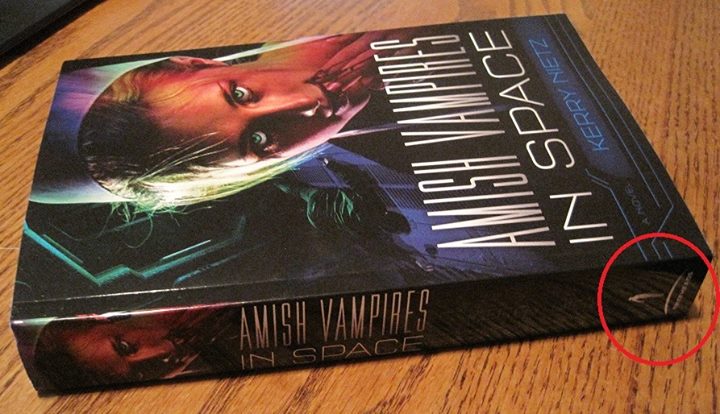

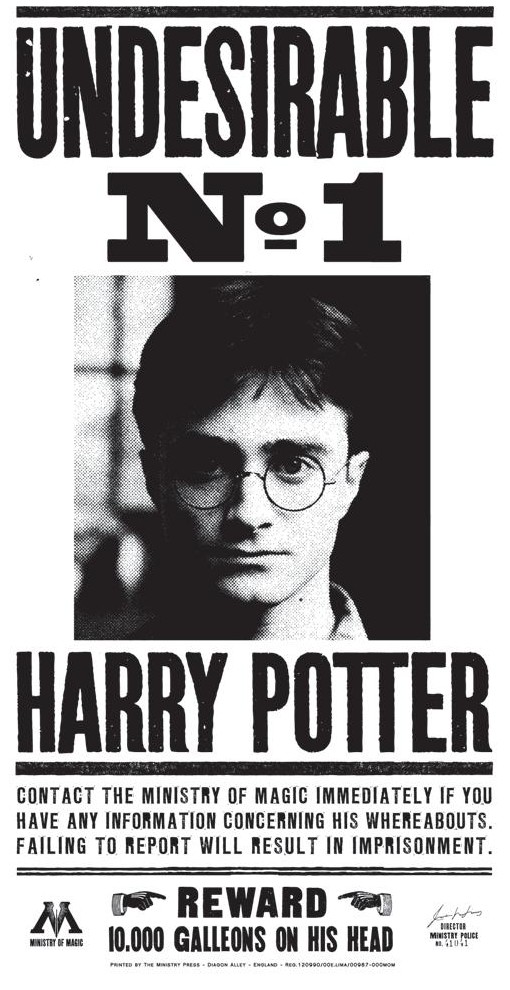

And therein lies the controversy. Speculative author Mike Duran, in his most recent blog post, “No Zombies Allowed! (In Christian Fiction),” took exception to James’s statement, keying in on his example of zombies as creatures presenting “a view of the world that contradicts God’s Word.”

Here’s Mike’s conclusion:

And thatâs the rub with this approach. Forcing fiction to neatly fit your theology is a losing proposition⌠at least, if creative storytelling is your aim. (Emphasis in the original.)

And later

I have long argued that one of the inherent problems with Christian speculative fiction is that Christian spec-fic, by its very nature, cannot be speculative enough. We impose overly strict theological expectations on our fiction. (Emphasis in the original.)

In turn, spurred by Mike’s thinking, I have long argued against both of his conclusions (which he also stated in posts such as “Can Christian Theology And Speculative Fiction Coexist?”): 1) that a Biblical framework must by definition limit our imagination (and in this stance, I’m also disagreeing with James Somer’s position regarding what specifically falls into the category of misrepresenting the way the Bible shows our world), and 2) that Christians ought not “impose overtly strict theological expectations on our fiction.”

First, a quick summary of some of the previous Spec Faith posts, such as last month’s article “In Which You Eavesdrop on a Conversation With Myself” by Yvonne Anderson, shows that Scripture itself engages in speculation about the way the rest of the Bible views the world.

In addition, I suggest that the Christian is the best person to imagine. (See, for example, â’Christian Speculative Fiction’ Is Not An Oxymoron”). God has made us in His own image–which would suggest that we are, by nature of our similitude to Him, creative beings, though we cannot create from nothing. Rather, what we create comes from something already made, and therefore, from God’s world. We simply re-fashion what exists into something of our invention. Of course this is true of all humans. Nevertheless, the Christian’s imagination has been baptized by Truth.

Speculation, then, is not the problem.

The error, I maintain, is Mike Duran’s position that theology ought not be “imposed” on fiction. In my way of thinking, that statement is like saying, realism ought not be imposed on characters.

Instead, if anything should be true in fiction, theology–or “religious beliefs and theory” about God–ought to be true. From “What Is Intellectual Rigor?”:

Our themes need to square with Scripture. This point is perhaps the most complex issue for the Christian. Some writers sacrifice theme for the sake of art. However, the most artfully told story that says something untrue is nothing more than an artful lie.

Some readers, and as a result, some writers, may become enamored with the beauty of the language, the depth of the characters, the realism of the world, or the intrigue of the plot. But a lie is still a lie. Good art will not only be beautiful but truthful.

(Emphasis added.)

Of course, no single work of fiction (or series) can tell the truth about everything–even if we limit “everything” to what we know from the Bible about God and His work in the world. Let’s face it: Truth is too big. One story can’t encompass it.

Of course, no single work of fiction (or series) can tell the truth about everything–even if we limit “everything” to what we know from the Bible about God and His work in the world. Let’s face it: Truth is too big. One story can’t encompass it.

However, good stories will tell some aspect of truth without muddling it or bogging it down with a lot of untruth. I’ll make the comparison again with fictional characters, which writers and readers alike seem to believe should be depicted realistically.

Would a character seem realistic if at some points in the story he were assigned two legs and at other stages, four? Clearly not. Now a world could be envisioned in which a character did have four legs; one might even exist in which the number of legs characters have, fluctuates. But that this imagined world worked this way must be shown if the change is to be believable.

Otherwise, readers would assume the author had made a mistake–perhaps left out the scene in which the character gained the two extra legs or that an editorial error left the discrepancy in place. At worst, the reader would fall into complete confusion.

So too with inerrant theology. Is there an omnipotent, sovereign, good God, or does a person look within to find enlightenment? The two beliefs are not compatible. One is Truth and the other, error.

Can both positions reside in a story? Certainly. Because there are people who hold those two disparate views, there can be characters who do also. But if an author doesn’t finish a story well, a reader may be left believing that either position is equally true.

There are writing tricks available for authors so that a clear presentation of the Christian worldview can be shown as true. Readers won’t feel preached to. They may disagree, but there won’t be any confusion about what the story has shown (see for example, the Narnia stories).

There are writing tricks available for authors so that a clear presentation of the Christian worldview can be shown as true. Readers won’t feel preached to. They may disagree, but there won’t be any confusion about what the story has shown (see for example, the Narnia stories).

On the other hand, when an author comes to her story believing that she should not show theology, there’s the clear possibility that no Truth will emerge and readers will be left to read into the story whatever they will.

My contention is that such stories fall down on both elements that define art: they don’t depict truth and, as a result, they aren’t beautiful.

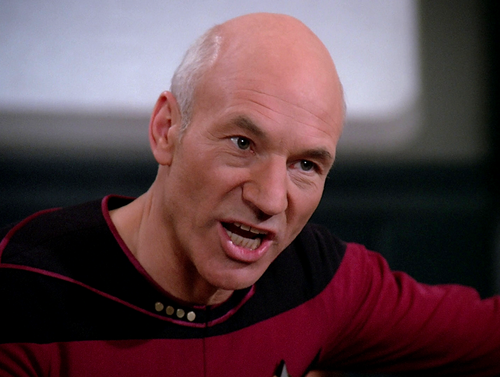

![â[Our decision today] will reach far beyond this courtroom and this one android. It could significantly redefine the boundaries of personal liberty and freedom: expanding them for some, savagely curtailing them for others.â](http://www.speculativefaith.lorehaven.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/startrektng_themeasureofaman_picardchooseslife.png)