Jesus, Thank You For Fantastical Stories

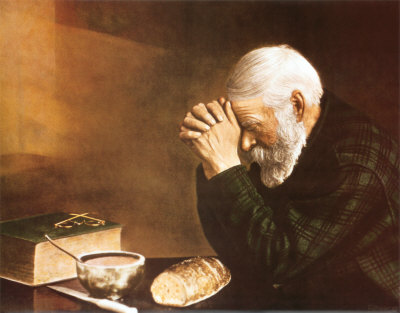

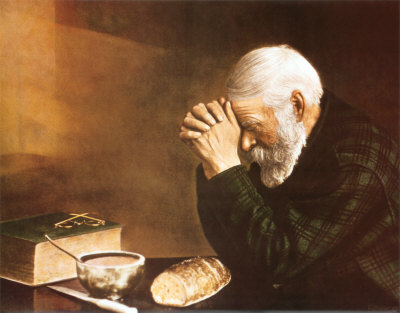

Once upon a time, I drifted away from the habit of saying prayers before meals.

Once upon a time, I drifted away from the habit of saying prayers before meals.

My reasons were ridiculous. I was going through the kind of phase in which you assume that just because a practice isnât in the Bible, thereâs no point to it, and in which you believe a practice could be âlegalisticâ just because itâs a routine.

Iâve come back to praying before meals, though sometimes I still forget when Iâm eating alone. My prayers are simple and havenât changed much since childhood. Thatâs okay. No one said that if you canât pray a âgrown-upâ prayer you might as well stop. In fact itâs the opposite attitude thatâs legalistic and just plain immature. He said, âPray without ceasing.â

Now Iâm trying to expand the practice. I wondered: Why Do we only pray before meals and not also before or after receiving other good gifts that God gives us?

Scripture condemns demon-influenced false teachers who claim marriage and some foods are somehow unspiritual. On the way Scripture says God created food âto be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and know the truthâ (1 Tim. 4:3). For such people this thanksgiving is not automatic. Itâs a conscious action. God even states that âspiritualâ practices, Scripture and prayer, are his peopleâs intentional means to enjoying other gifts:

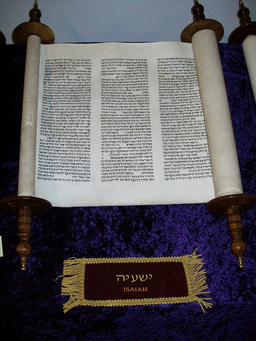

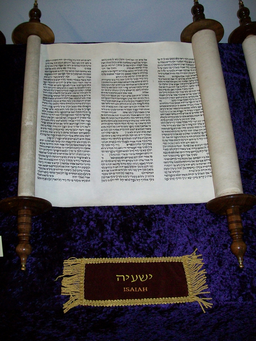

For everything created by God is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving, for it is made holy by the word of God and prayer.

â 1 Tim. 4:4â5

I read this in light of SpecFaithâs gift-in-focus: fantastical stories.1 Hereâs what I see.

I read this in light of SpecFaithâs gift-in-focus: fantastical stories.1 Hereâs what I see.

- Everything created by God. No, God doesnât directly create fantastic stories. Humans do, by seeing the world, taking parts, and arranging them in new ways. But God also does not directly create food. Humans do, by seeing the world, taking parts, and arranging them in new ways. This is why I tend to take what the Bible says about food, and the abuse of food, and apply the same principles to fantastical stories.

- Is good. This continues from Godâs original creation. He does not create bad things.

- And nothing is to be rejected. So donât be legalistic. In fact, thatâs demonic doctrine.

- If. This is a huge if. Itâs the catch, the condition. Otherwise perhaps we should reject the food, the fantastical story, or the thing â even a good thing that God has created.

- It is received with thanksgiving. Humans cannot skip straight to the gift-enjoyment. Instead we must receive good gifts with conscious and intentional gratitude to the Giver. Otherwise the above if would disqualify us from enjoying even the good gifts.

- For it is made holy. This is confusing, for if a food or fantastical story or any other gift is created good then why does it still need be made holy? John Piper preached a good sermon on this. I wonder if Paul has an implicit understanding that the gift must be made holy for us. Itâs not the gift that has a persisting flaw. Itâs ourselves.

- By the word of God and prayer. If youâre like me and youâve long since grown tired of evangelicalsâ overemphases of âspiritualâ tasks like Bible reading and prayer, please donât. Hereâs the key: All that Bible reading and prayer is crucial for our chief end. And in some sense these tasks remain âoverâ other gifts we enjoy such as food and fantastical stories. Why? Because we need the word and prayer to make holy our use of the other gifts. Otherwise we canât enjoy them. Otherwise we would be untrained, and our âjoyâ would be phony. We would be thankless thieves who rob the Giver.

So to enjoy a fantastical story, I should be seeing that story in light of Godâs word. Thatâs the only way to make the story holy for me. And I should be seeing the story in light of prayer. I must consciously, intentionally decide to receive the story with thanksgiving. Iâm sure there are many ways we can do that. But the first that comes to mind is a prayer before the story âmealâ â a prayer very similar to the kinds of prayers people have prayed before eating.

What kind of thankful prayer would you say before or after receiving a story? Hereâs mine.

Jesus, thank You for fantastical stories. Thank You for giving people the abilities to make these stories and show You, each other, and the world more of what You are like, more of what people should be like (or what they shouldnât be like), and more of what Your world should be like (or shouldnât be like). Thank You for human creativity, reflections of beauty, echoes of truth. Thank You for the ideas of magic and other worlds and amazing heroes.

Thank You so much for this particular story. It was amazing. Youâve gifted the storytellers with so many talents. May they trace their talents back to You and show You thanks. Thank You for the writer(s), artists, director(s), musicians, technical providers, everyone who helped make this story amazing. Thank You for that awesome line or that amazing moment.

Thank You that the good heroes won in the end. Thank You that the beauties make me weep for joy even when Iâm not thinking about You as the source of all real beauty. Thank You that the storyâs truths and challenges make me wrestle with ideas in my mind. Please help me continue to chase after You as the source of all beauties and truths. Please keep me from ever believing the notion that this âtrainingâ by the word and prayer is unnecessary. Help me to keep longing for perfect joy in You and reject any sin or abuse of Your gifts that gets between me and You. And help me to keep being thankful for fantastical stories. Amen.

- However, most or all of what I say here directly applies to all popular culture in general. ↩

distinguished by – and judged for – bloodshed and magic: “

distinguished by – and judged for – bloodshed and magic: “

Hero 6 is a movie of enormous creativity. From the futuristic (or AU) world of San Fransokyo to a glimpse of what I can only imagine to be some sort of fourth dimension; from the robots and other tech to the incredible CGI that brought them to full glory â the cleverness of this movie is wonderful.

Hero 6 is a movie of enormous creativity. From the futuristic (or AU) world of San Fransokyo to a glimpse of what I can only imagine to be some sort of fourth dimension; from the robots and other tech to the incredible CGI that brought them to full glory â the cleverness of this movie is wonderful.