A Rich Web

For the longest time, I thought Easter eggs were a tradition mainly for children. I thought they were one of the secular trappings of Easter, like the Easter bunny. Not that this made them bad – I’m not the Scrooge of Easter here – but still, to me they had no Christian meaning, nothing but the most casual linkage to Easter.

And then, last week, I learned better. Eggs were once an integral part of the Christian observance of Easter, due mainly to the  Lenten fast. As long ago as the fifth century, Socrates Scholasticus noted the custom of abstaining from eggs during Lent, and by the end of the seventh century the Church was laying it down as a universal practice: “It seems good therefore that the whole Church of God which is in all the world should follow one rule and keep the fast perfectly, and as they abstain from everything which is killed, so also should they from eggs and cheese, which are the fruit and produce of those animals from which we abstain.” (Canon LVI of the Council in Trullo)

Lenten fast. As long ago as the fifth century, Socrates Scholasticus noted the custom of abstaining from eggs during Lent, and by the end of the seventh century the Church was laying it down as a universal practice: “It seems good therefore that the whole Church of God which is in all the world should follow one rule and keep the fast perfectly, and as they abstain from everything which is killed, so also should they from eggs and cheese, which are the fruit and produce of those animals from which we abstain.” (Canon LVI of the Council in Trullo)

Centuries later, Thomas Aquinas would write that because the Lenten fast is “the most solemn of all”, it “lays a general prohibition even on eggs and milk foods”.

The Catholic Church no longer observes Lent so strictly, and most Protestants do not observe it at all. Only the Orthodox Church still prohibits eggs during Lent. Yet to this day we live with the legacy of a fast we have not only given up, but forgotten.

Because “milk foods” were forbidden during Lent, households would use them up before Ash Wednesday. In the Orthodox Church, the week before Lent was called Cheesefare Week. Shrove Tuesday (the day before Ash Wednesday) was known as Pancake Tuesday in Great Britain; my Lutheran grandmother called it Doughnut Day and would make doughnuts, although her family did not keep the fast in the old way. In other countries, Shrove Tuesday had other names, and was marked with similar customs of food and holiday: Bursting Day, Carnival, Fat Tuesday – which is, in fact, what Mardi Gras is, and what it means.

On Easter Day, the fast ended, and Christians ate again meat, cheese, milk – and eggs. Before partaking again, people would bring these foods to the church to be blessed by a priest – and there is, in fact, a traditional Easter blessing for eggs. In Ukraine, which has an elaborate tradition of Easter eggs, the decorated eggs would be blessed by priests before being given to family members.

Beyond the significance Easter eggs once had in marking how Lent’s abstinence turned to Easter’s rejoicing, there is a very old custom of dyeing eggs red to symbolize Christ’s blood. There are legends of eggs miraculously turning red at the first Easter, variously involving Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of Jesus, and even Simon of Cyrene.

This web of rich and potent customs, and even its weak modern legacy, is a testament to how profoundly religion molds culture. And it makes me wonder again why religion – one of the most vital parts of any culture, shaping everything from individuals’ inner selves to society’s outward customs – is so neglected in speculative fiction as an element of world-building. Even when it appears as a matter of worldview, it can be little or nothing to the world-building.

This web of rich and potent customs, and even its weak modern legacy, is a testament to how profoundly religion molds culture. And it makes me wonder again why religion – one of the most vital parts of any culture, shaping everything from individuals’ inner selves to society’s outward customs – is so neglected in speculative fiction as an element of world-building. Even when it appears as a matter of worldview, it can be little or nothing to the world-building.

In secular sci-fi, religion is often absent without explanation. Perhaps this is convention, perhaps it springs from the old belief that science will displace religion, perhaps it reflects the authors’ own irreligion; I have a notion that those who discount religion in their own lives are likely enough to dismiss it in their fiction.

In Christian fantasy, religion may be present as a matter of individual belief, but it is often culturally absent. Characters may talk about God, usually in vague monotheistic terms, but there is none of that cultural imprint all genuine religion leaves, in stories, songs, feasts, fasts, decorations, and word formulas (“I swear on a stack of Bibles”). I can count on one hand all the times I’ve seen anything like a church or temple in Christian SF – and that’s something everybody does. Jews, Christians, Muslims, pagans, Buddhists: We all end up raising a building.

So why don’t people in fantasy or sci-fi? Are secular authors uninterested in religion, or are Christian authors trying to stay out of the theological weeds? Is it too much trouble for authors to devise a religion to build into their world, or is the whole question too inevitably enmeshed with real-life religion? Or am I overthinking this, and authors no more have a special reason for neglecting religion than they have for neglecting other aspects of world-building?

What do you think?

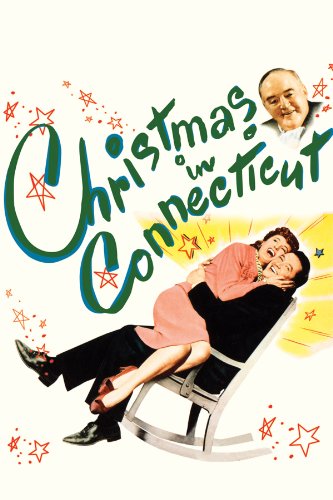

called Christmas in Connecticut. It had every appearance of being a quaint, old-time movie, until I realized that every character in it was a jerk. The heroine wrote a column for a magazine, a job she had gotten by lying to everyone about her life. With her boss about to find out, she agreed to marry a man who could bail her out, and together they commenced Operation Fake Out the Boss. Or as the movie is called, Christmas in Connecticut.

called Christmas in Connecticut. It had every appearance of being a quaint, old-time movie, until I realized that every character in it was a jerk. The heroine wrote a column for a magazine, a job she had gotten by lying to everyone about her life. With her boss about to find out, she agreed to marry a man who could bail her out, and together they commenced Operation Fake Out the Boss. Or as the movie is called, Christmas in Connecticut.