No Story Is Safe

My favorite stories can be used for evil by cults, killers, sorcerers and manipulators.

My favorite stories can be used for evil by cults, killers, sorcerers and manipulators.

So can your favorite stories.

No story is safe. No matter how wholesome, how “evangelical,” how values-based, how conservative, how artistically edgy, how moral-sentimentalized, or how “Biblical.”

Heard someone misuse verses to try to control people? Not even the Bible is safe.

Fantasy

I must spend the most time here.

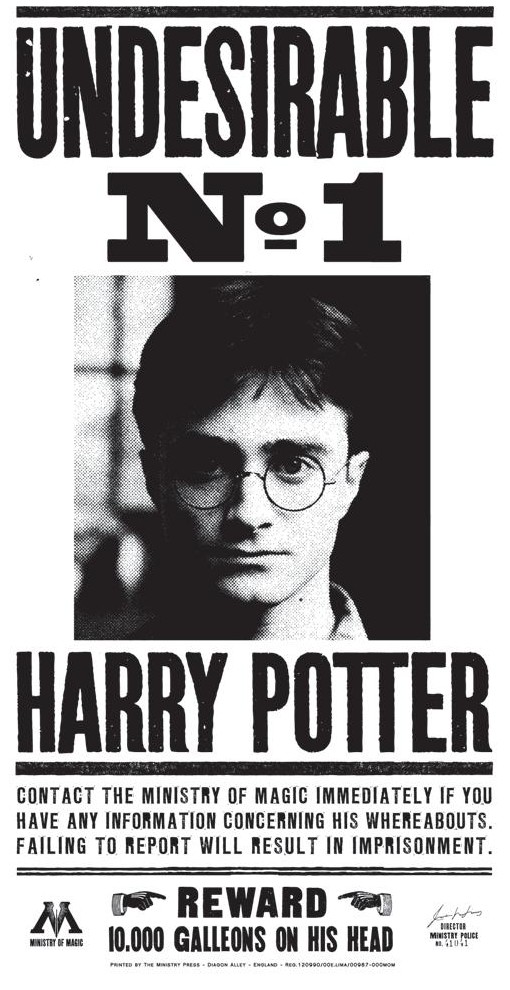

A chap called Tyler Deaton used the “holy trio” of great fantasy to commit flagrant sin. According to The Rolling Stone1, Deaton — an active participant in the evangelical charismatic group “International House of Prayer” — was nuts about The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, and especially the Harry Potter series.

Potter? Some would say that was the problem right there, but Narnia by C. S. Lewis is safe.

The group members began comparing themselves to the four Pevensie children in The Chronicles of Narnia, who enter a universe mastered by evil, win renown as soldiers in the army of a resurrected Messiah and finally assume their places as kings and queens of a renewed world.

SpecFaith readers know my stance on all three fantasy series. They are beautiful and truthful. At least two are by faithful Christians; the third is by an author (J.K. Rowling) who is clearly familiar and respectful of Biblical morality and Christ’s hero’s journey.2

SpecFaith readers know my stance on all three fantasy series. They are beautiful and truthful. At least two are by faithful Christians; the third is by an author (J.K. Rowling) who is clearly familiar and respectful of Biblical morality and Christ’s hero’s journey.2

But if we believe great fantasy is safe, this should petrificus totalus us.

“In the years I was with him, things were constantly happening that I had to shrug away as being ‘the work of the Holy Spirit,'” says [college friend Boze] Herrington. “Tyler would raise his voice and say, ‘Jesus!’ and the neighbor’s music would immediately stop. He would tell the birds to fly away and they would fly away. He would place curses on my appliances so they wouldn’t work.”

For every real-world equivalent to Harry Potter, who uses magical gifts for good, there is a Voldemort. And Voldemorts crave “real” magic — to manipulate their worlds and others.

Fantasy stories are not safe.

Romance

![]() Good readers can enjoy romance as worship of God. In a story primarily about pre-marital3 love between a man and a woman, a reader can imagine, even subtly, the sacred love of Christ for His Church. Just as in real marriage. As in the committed and sensual love exulted by the Song of Solomon. As in his or (most likely) her own marriage.

Good readers can enjoy romance as worship of God. In a story primarily about pre-marital3 love between a man and a woman, a reader can imagine, even subtly, the sacred love of Christ for His Church. Just as in real marriage. As in the committed and sensual love exulted by the Song of Solomon. As in his or (most likely) her own marriage.

Bad readers abuse fictional lovers. We’ve all heard of such cases. One is in my mind right now. They pine for people or situations that don’t exist. They use stories as an escape out of, and not to enjoy, the real world. They grow discontent. They endorse their own lusts.

Romance stories are not safe.

Mystery/suspense

Good readers can indulge in a well-done who-has-done-it. They can appreciate an author’s skill in planting clues, researching crime-scene investigation, delving into the darkness of sinful individuals and organizations. They can grip their pages or theater armrests during heart-pounding scenes. They can anticipate the capture of the guilty and justice being done.

Bad readers abuse the system. They obsess with society’s sins that have been dramatized — often too sanitized or too shallow — for the “safe” benefit of fans. They may become paranoid about serial killers or secret societies. Even craving feelings for their own ends is a “minor” sin.

Mystery and suspense stories are not safe.

Amish/historical

Good readers can appreciate the simple virtues of a bygone or contemporary society. They can explore a mostly-faithful recreation of a strange-seeming religious group from the perspective of a follower or ex-follower. They can let their minds time-travel to what is effectively a fantasy realm — an “elseworld” that’s simply closer to actual history. They can appreciate the research of a truer-to-life story.

Bad readers wish they could join that other existence. As with romance, they compare the “perfect” icons of the caricatured past or Amish to their own families and wistfully grieve the difference. Even “nonfiction” evangelical appeals to recover some lost era when men were men, women were women, and all learned on a farm can become twisted fantasies.

Amish and historical stories are not safe.

Children’s entertainment

Good readers know that evangelical books or discs are only a means to a greater end. Their promised Moral Values are only part of this complete breakfast that must include wise, customized training of children to learn God’s Law, their own sin, and above all, Christ.

Others presume that character instruction by wholesome characters is all that children need from stories to understand God’s love and righteousness.

Evangelical children’s entertainment stories are not safe.

- Love and Death in the House of Prayer, Jeff Tietz, Jan. 21, The Rolling Stone. ↩

- Learn more at Why I Don’t Shut Up About ‘Harry Potter.’ ↩

- It’s always pre-marital, though. Have you noticed? ↩

I think your article is missing a conclusion. So anything can be twisted for evil. What then? Be careful not to do that?

My hubby and I are watching a playthrough of Bioshock Infinite right now. It takes place in the early 1900s on this floating city in the clouds, where a crazy prophet dude has constructed this society where the founding fathers are worshipped as saints and all things America are elevated to religious fervor. Of course, as with all Utopias, it has a dark side and there are parallel realities and powers involved. It’s just interesting to see something as basic as American history twisted like that.

‘Tis more of a discussion-starter — though I’m not ruling out a part 2 next week.

See also yesterday’s news item Stop Asking ‘How Much Is Too Much.’ Which also jibes with Rebecca Miller’s Monday column Reading Choices: Down With Snobbery. (When all genres have associated risk, you can’t claim one is better or more Christian than another.) Which also jibes with last week’s most popular news item, Does the Devil Lurk Under Bonnets?, based on a tweet from Mike Duran, stirrin’ things up like a paranormal-suspense-author boss.

I think the point is that Christians tend to assume some genres are safer than another, but any genre can be an occasion of sin, to use Catholic terminology. The argument against fantasy by many Christians tends to isolate that genre specifically as opening the door to Satan more than westerns or historical or other such realistic genres.

I don’t really like using safe in this context though. There’s too much focus on safety in artistic works, and I think this gives them much more power than they have while at the same time reducing our power as believers. That art can somehow make us believe something against our own will.

Goodness, you’re going to make me afraid to write anything for fear of leading anyone astray!

I’m afraid the human heart is quite able to lead anyone astray quite on its own, using/abusing anything it can get its grimy little sinful hands on.

Ah, we’re being cynical today? I’m pretty awesome at that.

What exactly is “safe” supposed to look like in terms of stories? Something that doesn’t challenge us? Or just something that doesn’t challenge us in ways that threaten the tribal boundaries? What are the merits in being “safe” in this sense? Is there even any real danger to guard against, or it is just paranoia? What are we protecting? To repeat a question I asked earlier, what is the purpose of this separatism we feel obligated to maintain, as if Christians aren’t major players in plenty of this country? The vast majority of Congresscritters are Christian. Even if it’s only in appearance, the appearance appears to be necessary for them.

I’m in favor of chucking separatism out the window.

“Christian.”

Another thing we can chuck out the window: No True Scotsmanning all the denominations we don’t agree with, especially when we’re talking sociology more than theology.

Notleia, that’s simply not true. Words mean things. The word Christian may have many meanings, but it also has non-meanings. ‘Tis a false flag to claim that saying so, or challenging your (at best) non-definition, is simply a “no true Scotsman” fallacy. (Denominational differences is another issue entirely; you’ve missed the point of my challenge. 🙂 ) I’m in fact asking you to present your definition of Christian, then show how it applies to (supposedly) most U.S. congressmen.

If you don’t wish to go there, I suggest the thought (if that) behind what you end up proposing is this: we must make the word Christian an utterly useless word.

And at its heart, this is actually an abuse of language altogether.

If you will not take that from me, consider it from someone much wiser. This debate far predates anything you and I discuss here. I suggest that if either of us act like this “little” controversy only began the day either of us were born, we would both be guilty of what the below author called “chronological snobbery.”

How does C.S. Lewis go on to define his own use of the word “Christian”?

Most evangelicals and fundamentalists have deepened the sense of the word. The problem that I’ve always had with my faith is that it’s not enough to be a Christian. One most also be “saved.” One must make a special commitment besides believing the truth claims of Christianity — the deity of Jesus Christ, His atoning death, His resurrection. The denominational schism is relevant here, because many evangelicals and fundamentalists draw a line to exclude entire denominations from Christianity, if those denominations are perceived as only practicing “dead religion” rather than promoting “a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.”

In doing this, evangelicals and fundamentalists are doing what C.S. Lewis believed we must not do:

Trying to determine whether a professing Christian is or is not “saved” based on that person’s personal history or denominational affiliation is taking the judgment of God into human hands. And I think it’s pretty clear that calling professing Christians “unsaved” is the same as calling them non-Christians.

To a certain extent. However, many people who call themselves ‘Christian’ are not believers at all. They may be cultural Christians – i.e. they get married in a church, celebrate Christmas etc – because they’re traditional and nice things to do. They may identify with a denomination for cultural/family reasons. But their actual beliefs may be anything from vaguely theist to atheist. And I think we can definitely say those people are not ‘saved’.

The same is true of child-abusing religious leaders, greedy “Christian” moneymongers, and other hypocrites. If we refuse to allow someone’s claim of Christianity to be put to the test — in the same gentle yet firm ways mandated by Jesus Christ and the Apostles — then we’re simply tossing the keys to the deceived and the deceivers and inviting them to drive their religion as fast as they like.

Are you kidding me? Go to this Wiki page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/113th_United_States_Congress#Members, click on all of the names there, and look at that box on the right side of the page with the photo and the personal information. Religion is listed near the bottom of that box. I clicked on five names at random, and you know what I found? Roman Catholic, Roman Catholic, Methodist, Anglican, and Roman Catholic. Are you going to sit there and tell me those aren’t Christian?

Once again I’m afraid you’ve misunderstood my meaning. I couldn’t care less (at this point) of the particular beliefs or denominations of specific government leaders. My challenge was only directed to the belief that one can use “Christian” to mean pretty much anything. I’m saying that if we refuse to say that “Christian” can mean at least some things and not others, then the term has become an absolutely useless term, and thus it’s also useless to debate whether someone “is” or “isn’t” without definition.

When Jesus Christ Himself says some people will feign to believe in Him but prove only their evil, we should listen.

I don’t even know what the shell you’re trying to say. The only useful definition of “Christian” is “follower of Christ.” The problem is that “follower of Christ” is a much more subjective idea, dependent on things like interpretation and yada-yada. But an ugly, poorly executed sofa is still a sofa. Fred Phelps still falls under the umbrella term of “Christian,” as sad as that makes me feel.

But that’s only opinion, leia. What do you think about Jesus Christ’s words that yes there are people who only call themselves Christians, but aren’t? I could cite reams more verses in which Jesus Christ, the founder of Christianity and the Son of God, specifically told His people to watch out and call out false teachers who only profess to be Christians.

True story: In some parts of Glasgow there is a big divide between Catholic and Protestant (complicated by politics and football).

Some boys went up to another boy and demanded, “Are you Catholic or Protestant?”

“I’m a Muslim,” he replied.

“But are you a Catholic Muslim or a Protestant Muslim?” they asked.

Me too. In fairness, I think we have to admit that separatism was more important in the old days of imperial state churches.

At the same time, I don’t think separatism is part of orthodox Christian faith — “Biblical” faith, whatever. Because it’s often impossible to tell the difference between a real Christian and a mere “Christian,” all sub-cultures based on Christianity and/or the Bible will be merely “Christian” by default. Scripture warns us not to love “the world,” and I believe that Christian sub-cultures are as much part of “the world” as secular culture is. Because there is no pure culture, separation is impossible, except on a personal and individual level.

I love the subversiveness in this post. It’s structured loosely like typical misinformed Christian paranoia, but it serves to critique both the scare-mongers’ extreme separationist tendencies and their blunt tactics. At the same time, it offers dash of self-critique, acknowledging the limitations of enjoying entertainment.

I wish the fiction that I’ve been reading lately could be half this subversive!

Subvert subversions! Then subvert subverted subversions!

Aslan is not a tame lion.

Hmmm …

It sounds like you would agree with me that if we expect anything, including God Himself or His Word, to be “safe,” this is fundamentally a theological error.

I myself would like to see another piece with some specific ideas, brother. I believe I have an idea what you would say via reading your pieces on here, but some more discussion is always good.

I think that the major problem with me for any genre is to take “escapism” too far. It is so easy for me to want to be in the world of the book or comic I’m reading. I need to keep my eye on the eventual, perfect promise of the New Heaven/New Earth. Just some thoughts from my devotions the past few days, combined with my reading lately.