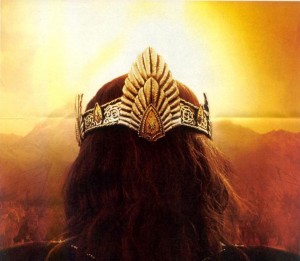

Jesus Christ: Return Of The Warrior-King

We are all familiar with the image of Christ as the lamb of God led passively to the slaughter. Having just left behind the Christmas season, we’re also intimately familiar with Jesus come in the flesh. We recognize Jesus the preacher, wandering through Judea and speaking to people about the coming of the Kingdom. Yet there is one image that is less familiar to us, which is Christ the warrior.

We are all familiar with the image of Christ as the lamb of God led passively to the slaughter. Having just left behind the Christmas season, we’re also intimately familiar with Jesus come in the flesh. We recognize Jesus the preacher, wandering through Judea and speaking to people about the coming of the Kingdom. Yet there is one image that is less familiar to us, which is Christ the warrior.

This lack in our visual vocabulary is most unfortunate, because it balances out the other pictures. Jesus the conqueror riding forth to do battle with His enemies in Revelation is the description of what Christ is like after the Ascension, seated on the right hand of Heaven, bearing a sword and riding out on the clouds to throw down his enemies. (I’ve often thought a great title for a commentary on the book of Revelation would be The Return of the King.)

This picture of Jesus as warrior-King is particularly relevant for the speculative fiction genres and their Christian readers because it gives us a window into understanding these genres in a Christian way. To this effect, I want to look at one specific passage in the New Testament that speaks of Christ in fantasy-esque terms.

Hebrews 2:10 (ESV) reads: ”For it was fitting that he, for whom and by whom all things exist, in bringing many sons to glory, should make the founder of their salvation perfect through suffering.” The passage is speaking about Christ and the ESV refers to Him as the “founder” of salvation. The Greek word for is archegos, of which “founder” is a poor translation. The word actually means “captain” or “prince” of salvation. In its fullest sense, the word means champion, and actually refers to the ancient war tradition in the ancient near east. When two armies met on the battlefield, before they would charge they would send out their greatest warriors to fight one another. The side whose champion lost would be forced by their code of honor to surrender (though this often didn’t happen either).

Thus Christ pictured as the lamb led to slaughter is not the only image we’re given by the Bible about His work on the cross. Christ was sent out as our champion, to do battle with the champion of the forces of sin and darkness, namely, the Devil. And, as Hebrews 2:15-16 goes on to say, Christ defeats the Devil in hand-to-hand combat: “Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same things, that through death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery.”

William Lane, in his Word Biblical Commentary on Hebrews, writes,

The language of Heb 2:10, 18 displays a close affinity with the descriptions and manegyrics of some of the most popular cult [religious – ATR] figures of the hellenistic world, the “divine hero” who descends from heaven to earth in order to rescue humankind. Although Jesus is of divine origin, he accepts a human nature, in which he can serve humanity, experience testing, and ultimately suffer death. Through his death and resurrection he attains to his perfection, wins his exaltation to heaven, and recieves a new name or title to mark his achievement in the sphere of redemption. This description, Knox observed, represented Jesus in much the same light as the divine hero figures of the pagan world, of whom Hercules was the most prominent. (p. 56)

By using the term “champion,” the author of Hebrews argues that Christ is the fulfillment, not merely of Jewish archetypes and shadows, but also of pagan ones as well. The earthly tabernacle and sacrifices in the Old Testament were “types and shadows” of Christ – and not them alone, because even pagan stories serve as “types and shadows” of Christ’s work as well. Christ fulfills not merely the Messianic figure in the Jewish worldview, but the Herculean figure of the Gentile worldview as well. Lane goes on, writing that “Hearers familiar with the common stock of ideas in the hellenistic world knew that the legendary Hercules was designated ‘champion’ and ‘savior,’ (p. 56-57).

Readers of Hebrews would

almost certainly interpret the term archegos in v 10 in the light of the allusion to Jesus as the protegonist who came to the aid of the oppressed people of God in vv 14-16. Locked in mortal combat with the one who held the power of death, he overthrew him in order to release all those who had been enslaved by this evil tyrant. This representation of the achievement of Jesus was calculated to recall one of the more famous labors of Hercules, his wrestling with Death, ‘the dark-robed lord of the dead’,” (p. 57).

Jesus as Hercules, descending from a Kingdom long-lost to mankind to do battle with a “dark-robed lord of the dead” in order to set the captives free and restore justice to the realm by being crowned and taking the throne? If you’re anything like me, you just got chills. If that reminds you of your favorite fantasy series, it is because fantasy is the descendant of the ancient myth, as interpreted through the lens of Medieval romance. In short, fantasy presents the gospel in “types and shadows” in the same way that the myth of Hercules did.

This startling fact is helpful when we start thinking about “Christian elements” in fiction and what we should do with “secular” stories. Christian readers often wonder if an author “intended” for this or that to reflect the Christian story. Well, do we imagine the original pagans who told the Hercules myth intended for it to be read as a type or shadow of Jesus Christ? Obviously not. Does this matter to the author of Hebrews? No. Jesus as Messiah is the intentional fulfillment of an unintentional type and shadow written down and told by pagans. The creation and everything in it (including pagan stories) was made by Christ, “for whom and by whom all things exist.” The universe was made for Christ, by Christ, which means that all meaning in the universe (in order for it to be true meaning) was made by Christ, for Christ. Now, obviously we need to be clear that some reflections are better than others, some shadows are more difficult to see than others, some reflections more distorted than others, but they all make Christ plain.

The implication here is that instead of running from some kinds of stories or viewing them with suspicion, we must read and interpret them Christianly (since, according to Hebrews, the Christian interpretation is the correct interpretation). So when we’re reading a story (any story), the ultimate meaning of that story must point to Christ, even if the author’s heart is in total rebellion. All stories reflect Christ because all meaning has its beginning and its end point in the person of Jesus. This means that Aragorn is a type of Christ, as is Beowulf and Harry Potter and (sigh) Eragon. All stories are types and shadows of the world’s great champion, Jesus Christ, their meanings are all drawn up together into His being.

A. T. Ross is an aspiring speculative novelist with four unpublished novels under his belt, a committed Christian, amateur theologian, and avid reader. He is a Reviews editor for Fermentations magazine and writes occasionally for Fantasy Book Review. When he’s not working on one of his writing projects, he can be found reading at the public library or getting into mischief on his blog. He lives and churches in Ohio.

I find stories with that potrayal rare, and all the more rewarding when found.

Galadriel, I’m not sure I follow what you mean exactly. Do you mind expanding your thoughts?

Since there aren’t many stories that portray Jesus as warrior, I really enjoy those that do. Even the medieval “Dream of the Rood” was amazing.

Ah, I see now! Yes, I agree, they’re very powerful when done properly!

This article explains and clarifies everything I’ve come to understand in a fuzzy sort of way about the relationship between Christ and story/myth!

Now, if only I knew why the “real world” as we know it sometimes seems so much less epic and profound and satisfying than stories and mythology. All the epic meaning must be true; reality can’t be shallower than human imagination. All the epics have their source in Christ.

Paul, thanks much! Very glad it helped you.

If I might throw my two cents in the question of why reality seems “less” than an epic poem, I’d have to say, “thank the Enlightenment.” Yes, it brought us many good things, including indoor plumbing (for which much rejoicing!) but it did so at the expense of our ability to see the world as a magical place greater and deeper, more mysterious than we can imagine. The idea that through science and logic we can come to know the world fully is an Enlightenment idea passed on to us for generations. The recent attempts at a “unifying theory of everything” comes from the same assumption. The way back, it seems to me, must begin with “eyes made new” to see the mystery and “myth” going on before our eyes we have been too blinded to pay attention to. I count myself in the number of those trying to learn to see “through new eyes”!

Part of it is that we can’t see all the pieces. When reading a book or watching a movie, you’re privy to information the characters don’t have. You get a bird’s eye view and are perfectly aware the author is taking you somewhere. But to them….well, the LOTR book has a 14-year gap between the first two chapters. We’re reading the condensed version in a matter of hours. They lived it over the course of decades. Epics never feel epic to the people in them. So, since, as you say, reality can’t be shallower than human imagination, then how magnificent is the ending going to be? We’ll look back, one of these days, and we’ll see the full scale. We’ll be able to pull up the Great Movie Reel and watch the greatest epic in all eternity.

Interesting article, Adam. I kept thinking of Col. 1:13 – “For He rescued us from the dominion of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of His beloved Son.”

In the end, though, I had a question. You said:

What about a story like Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials in which he purposefully chose an anti-God position and made his heroes those who “killed God” in the end. How is that consistent with the idea that all stories reflect Jesus Christ through types and shadows?

I haven’t read Pullman’s books, but from what he said about them, he was purposeful in rejecting God and defeating God and His followers, advocates, believers. I guess I’m asking, shouldn’t we make room for those stories too, as sort of a counter to the truth? I think there are counter-truth stories that aren’t intentional, too. The types and shadows point away from Christ rather than toward Him.

Which, I guess, is why I think Christians need to be writing stories.

Becky

I was thinking of that series also. I’m guessing Adam may have an expansion, or a contrary thought. But this is my answer: Either we qualify Pullman’s stuff as not being within this definition of story, or else we refine the definition to mean a good story, with the structure of plot, protagonist, antagonist, seeming defeat, eucatastrophe, and so on.

But even Pullman behaves discordantly with his own professed worldview, if he ever tries to order his stories, have a “good vs. evil” theme, or infuse them with excellence in his craft — or even try to write a story at all.

However, he does seem to be an exception, as one of the few authors who overtly attempts to subvert the default Christian worldview of story.

I guess as I see it, the exception calls in question the rule. Plus, I don’t think it’s all that much of an exception. I think there are some stories that do draw from the Christian story, but I think there are plenty that draw from humanism which is a contradiction of what God has revealed. That someone with a humanistic frame of reference might do something self-sacrificial because he “finds goodness within” does not equate with what Christ did.

In other words, I think there are some stories that stumble upon the truth unintentionally, some that promote it intentionally, some opposed to it intentionally (Philip Pullman), nd some opposed to it unintentionally.

Man is not the same as the natural world in that what we do ultimately points to Christ. Think of the visual artists who create a blasphemous portrayal. Writers can and do do that too.

But “myth,” I think, is different than “story.” The larger than life explanations of the way the world works most often will have a semblance of truth, though I can envision someone writing an evolution myth that would be in contradiction to truth.

Becky

I still have to go back to “I didn’t catch any of it in book one.” Granted, I was 11 when I read The Golden Compass, but I was a kid who should’ve caught it and just thought “the daemon concept is cool.” I didn’t read the other two, but I do have to concede it never registered the “bad guys” were a warped version of the RCC. I remember flat characters and a confusing plot. If I’d read the other two back then, I’m not convinced I’d have seen the “dust” as the real God – or any god, for that matter. He might have been purposeful, but the church brat didn’t notice.

I dunno. I find it a bit ironic, is all. I’d never in a million years have compared The Golden Compass with The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, even as a child.

Per Stephen: There *is* a defined good and evil, if I remember. Evil people separate children’s souls (daemons) from their bodies. I don’t remember if it went any further than that.

I have a friend who read the other two, and she told me I wouldn’t like them. So I could ask her if she remembers anything.

Kaci, I think you’ve brought up a big issue: what did the writer intend versus what did the reader take away. Because an author intends an anti-God work, might he still reflect Christ? I don’t think it’s impossible.

But here’s the quandary. If one person sees Christ in the story, does that mean it is in fact reflecting Christ, never mind that thousands of others see it as an anti-God story?

John Granger, for example, wrote Finding God in Harry Potter (after book 5, if I remember correctly), and part of his argument seemed like an implausible stretch. I forget now whether it was because of his name associations or his numerology. The point is, I didn’t see what he saw, and I thought he was really grasping at that point to make something true that the author probably never intended. Does Granger’s seeing it make it so? Or might he be wrong in his view about the names (or numbers)?

Extrapolating the point, might someone who sees Christ, though a poor reflection, in His Dark Materials (as Adam seems to indicate in his comment), simply be wrong?

Becky

Becky, the entire point of my article is that the question of whether the author intended such a link is irrelevant. What’s more, it is impossible to maintain. The real issue is “Who are you letting define the world? Who gets to narrate the world?”

I appreciate your viewpoint and have even shared it in the past. But no matter which way I looked at it, it simply does’t work. Who gets to narrate the world? Does Christ get to narrate the world, or are we going to let other gods narrate the world? The rainbow has symbolized a lot of things to a lot of people, but does that change the actual, objective meaning of the rainbow given by God in Genesis and extrapolated throughout Scripture?

Since you oppose postmodernist relativism, why the sudden demand for subjectivity when it comes to literature? “He says, she says, who’s to say, really?” No, the Christian view of the world is the only objective view of the world. All things in creation, and all symbols in the world stand “in relation to” something else, and as Christians we cannot let that something else be anything but Christ. Dragons do not exist “in relation to” Baal, but Christ. The Phoenix does not exist in relation to fertility cults, but Christ. The Unicorn does not exist “in relation to” some New Agey cult, but to Christ.

So, since you mention Granger, alas, he is correct in two directions. One, he’s reading literature the way it’s meant to be read, and two, he’s reading it Christianly. (Also, three, Harry Potter is a Christian work and Rowling has said so, so even if it should matter what the author intended, Granger’s interpretations are far more likely to be correct that those dreadful books by Abanes).

This is not an excuse for a lack of careful study and examination of various works. But it means beginning with continuity with Christ and moving from there. As an old Christian philosopher once said, a non-believer attacking God is like a little boy who must sit on his father’s lap in order to be able to slap him in the face. He must always depend upon, and assume God in order to assault Him.

Becky, thanks. I would say (and that was precisely the point I want to address in another article, so this is a little preview!) that our thinking can go in two directions. One, we can say that while Pullman did his best to make the books anti-God, the core of the books still rotate around self-sacrifice by the characters – in other words, that while Pullman might have tried to get as far away as he can from God, he must ultimately build his rebellion with wood stolen from the Christian woodpile. Which is like trying to rebel against Beethoven by using motifs and ideas that Beethoven used in his symphonies. That’s one way to think about it.

Second, I threw a clarification in at the end of the article that not every type and shadow reflects Christ with the same clarity as others. By this all I meant is that a character can reflect the office of Champion and therefore by a type and shadow of Christ, while still being faithless in that office. We tend to want good Christ-figures or no Christ-figures, but what we, I think, need to see is that there are only faithful Christ-figures and unfaithful Christ-figures. Think about the office of “husband” for a second. There are good husbands and bad husbands, but the act of being a bad husband doesn’t make you a “not husband.” Adultery doesn’t remove the office, it reveals that you reflected the office poorly. So I would think about characters as types and shadows in that way – they participate in the “office” of Champion, reflecting the ultimate Champion, but their reflections can be good or bad, depending. So we can still have critical analysis of each individual and book. Achilles, for instance, is an example of a poor reflection of Christ as Champion, where Aragorn is a good reflection.

I hope that clarifies a bit.

Hi, Adam. Since I haven’t read Pullman, I can’t speak to the idea that he borrowed from the Christian woodpile. In a sense that has to be true since God created this world. All of it, then, could be thought to be part of the Christian woodpile. Unless, of course, we believe that evil is the anti-wood pile, the absence of God and therefore the antithesis of God. The recently deceased Christopher Hitchens used to say that he wasn’t an atheist as much as he was an anti-theist. He saw a difference, and I do too.

In that vein, I don’t see a writer like Pullman, who I suspect would classify himself as Hitchens did, writing a poor reflection of truth. To use your husband analogy, he’s not writing a husband as we know it. He’s writing a gay lover and calling him “husband.” He can say it all he wants, but he is not a true husband (because that would require a wife). Therefore, he is not a poor reflection of husband. He is a false one.

So with stories. There are stories, I believe, that do not reveal truth because they come from evil — from anti-God. They cannot reflect what they deny except through contrast in the same way that darkness does not show light except by being a contrast for it when it is shown abroad.

Men love evil, Christ said, and it is from that evil that some write stories.

Becky

Pretty much what Adam said:

It’s no different, I guess, than knowing that Star Wars has zen-Buddhist thinking in it, but we still use it to try to explain the Spirit; and knowing that The Matrix is a philosophical mutt, but we still try to use it to explain certain Christian concepts. The author’s intention can’t be dismissed, but that doesn’t mean we can’t still redeem the book or recognize universal truth when we see it.

Nicely said.

But even the display of “what God is not” can be inherently Christian in theme. God is not evil. God is not fickle. God is not faithless, abusive, manipulative, or cruel. God is not a speck of dust in a time piece that can be killed by a pair of children.

God is not Adam, who threw away his kingdom for a piece of fruit. God is not Eve, who deceived herself. God is not a murderer, nor does he resort to force when he doesn’t get his way. God is not made of wood, stone, or metal; he needs nothing and he does not need to be served by human hands. His ways are absolute and his mind is wise. He is not a king who can be toppled, weakened, or tricked. He is not a high priest who can only show up once a year with bells around his ankles. He cannot be approached the same way other gods are approached. He isn’t Moses, who in a fit of rage forfeited the Promised Land, and he isn’t Elijah, who became discouraged and ran away. He isn’t Jonah, who withheld good; he is better than the best father, better than the best husband.

Ah, Star Wars. The perfect example of the kind of movie I’m talking about. Also Avatar. These movies were explicitly anti-Christ. They were demonstrating a belief that rejects Him as Lord and Savior. Might some people find something spiritual in them, even something “Christian”? It’s not impossible, but because one person finds something, a la my John Granger illustration, does not mean the work itself is actually a reflection of Christ.

Becky

Pullman very much wanted to do just what you say and present like as darkness and darkness as light. Unfortunately, he failed. The books are full of right-side-up actions, light as light and dark as dark. I wouldn’t let my kids read them until they were much older and could apply critical faculties to them effectively, because there’s still a lot of bad husbandness in them. We would probably even agree about what in the books were darkness masquerading as light and light as darkness.

There’s no opt-in or opt-out policy to having a story be a husband or not. If you’re writing a book you’re dealing in archetypes that represent God. Lyra has a father, and all father-figures represent God the Father. Does Lyra’s father present God faithfully or unfaithfully? Go down each type and ask the same question. Unfaithfulness can only distort, it cannot negate or remove.

I’m guessing my phraseology was too convoluted in my earlier comment, Kaci. I am not talking about what God is not. I’m talking about Not God. His absence. There in is darkness since Jesus is the light of the world. Remove Him and all is dark.

As I understand Adam, he is saying even stories without the light of truth still shine some light.

I’m saying, I the reader may shine light on the story because of my worldview, but that doesn’t equate with the story itself having any light. Some have light unintentionally, but a story like His Dark Materials purposely calls darkness light and light, darkness. The only truth in those stories is whatever the reader brings. It’s not in the story.

Becky

Perhaps a lot of this has to do with the convoluted nature of man. Yes, he seeks after evil, and Jesus said. Yet Jesus also said that even evil people can do good things (Matt. 7). Somehow, both “total depravity” of man, and the “common grace” that God gives: the remnant image of God in man, the imago Dei, and the ability to do some good things, even relay truth — even if one is not transformed by it — are both equally true.

Thus I find it easy to believe that James Cameron, and even Phillip Pullman, are still using Biblical-truth “parts” even while they try to deny they exist. Like it or not, they are passing it along. And readers who know the ultimate Source of those truths will discern them — even if the authors did not consciously mean to use them.

This ongoing discussion is helping me hone exactly how all this is best articulated.

Stephen, as I said in my comment to Adam, it’s true that all humans are “using Biblical true parts” because God created all we’re using. There is objective reality, and if a writer reflects that in his story, then he is “using Biblical truth.”

Mike Duran wrote an excellent post on this topic, “Why a Judeo-Christian Worldview Is Essential to Good Fiction.” In part he said

I think Mike is making Stephen’s point — that good stories will point to Christ, even if unintentionally. Poor ones? Not so much.

That makes sense to me except I’d add a category for “Don’t point to Christ but away from Him.” It seems apparent to me that many writers intentionally aim to do just that. There’s an atheist forum, for example, discussing Mike’s article, and they are adamant in their disagreement. Here’s one sample:

Fiction reflects reality and part of reality, as Jesus said, is that some have rejected Him (see John 3:16-18). So some stories are going to be about those going their own way or chasing idols. Those stories by their contrast to the story of redemption do still show God but not because they are in some way pointing to Christ.

Becky

I’ve read Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. The first book was very good, the second was okay, the third book pulled out all stops and was a load of propagandist crap. I found elements of his series interesting and some concepts rather disturbing (eg. witches = good, Church = evil, but there are others). You can’t really say anything good about the third book because you can taste Pullman’s malice as he angrily rants at God and Christians. Does he have a point? In some cases, yes. There’s no ignoring that religion has done absolutely horrible things in the name of Christ. Pullman seems to have been especially hurt by such people. He doesn’t see any good in God and there being a spiritual reality. He is one of those truly antagonistic atheists. True healing comes from Christ, but he seems to run from everything to do with him.

And yet, even Pullman had to borrow from great Christian works to fashion his books. He took great chunks of Paradise Lost and inverted them, so that sin “knowledge-scientific revelation” as he saw it, was good, and spiritual revelation was another name for “close-minded but creative idiocy”. He took sections of Narnia and inverted them, he took elements from Lewis’ The Great Divorce. But in reading Pullman’s books, he unwittingly shows us how important, how necessary a spiritual reality really is. He shows us sin=knowledge as good but we don’t want that reality (well, as someone who has experienced Christ, I can see no good coming of it). Pullman shows us that we need a soul to understand ourselves, others and the world in which we live. Even someone like Pullman, who wants to destroy everything associated with God and religion, can’t do it. God shines through the books. Certainly not as strongly as many other books, but He shines all the same. He will not be silenced!

That’s a pretty good analysis of His Dark Materials. I read them as they were coming out. So I devoured book 1, and book 2 was good, but eh, where’s he going with this? Then the third book came out and the fanbase made this face:

:-/

He had great creatures and concepts, though. Like the elephants on wheels or the knife that cut through dimensions. And the daemons! My family still makes jokes about various pets being certain peoples’ daemons.

Thanks to you both. Like I said, I never read the other two because my friend told me they’d bother me. She’s usually right, so…yeah. Plus, I just didn’t like the first enough.

I understood, but I thought we were still on Pullman, who had a world in which God is killed (to my knowledge), not a world with no God.

I actually dislike both the Force concept and, much more strongly, the Matrix – the former for the dehumanization of people and the degradation of the divine to a disembodied thing; and the latter because Neo has to be the worst Christ-type ever created. I never saw Avatar. But The Matrix is a philosophical mutt and Star Wars operates in a kind of ‘neutral’ tone. Avatar looked, at best, animistic. I mentioned them strictly because, worldly or not, it’s still possible to pull a theme or two out of it…returning back to Adam, Stephen, and others. I mean, Doctor Who is incredibly humanistic, and this site has worn the thing out yanking redemptive themes out of it. I’m just saying there’s no reason not to treat Star Wars, Avatar, Twilight, and The Matrix in the same way.

But I’m likely on a limb here, having tried my hand at writing a world without God.

To the OP, Jesus as the Warrior-King has been one of my favorite images forever, so I’ve been very grateful for this post. The problem with forgetting the strength of God is that without his strength, he just looks weak. Rather than the potent image of the great warrior-king of Israel allowing the enemy to bind his hands and lead him into the enemy camp so he can defeat the enemy….it just…looks like a guy who couldn’t or wouldn’t fight. The most powerful person in the entire universe let some renegade demon and a pack of humans kill him. Then he killed Death.

Pullman obviously thought killing God was the noble and courageous thing to do. What he didn’t know was that what he intended to be a representation of “God” was really in his context a picture of the Devil, and his heroes who kill “God” are really Christ-figures who defeat the Devil. Even anti-theists can’t get away from the redemptive outline of transcendence, of breaking out of the box. That’s my theory.

From Christian‘s comment:

Hmm. That’s a lot of inversion. Doesn’t sound very original, though. Can’t atheism come up with something by itself, a new pleasure or new virtue, without having to steal and “invert” them? Even that method isn’t new. I wonder if he “inverted” Screwtape:

(Best read in the voice of Andy “Gollum” Serkis as Abysmal Sublimity Under Secretary

Screwtape, T.E., B.S., etc., of course.)

Of course, Screwtape hopes in vain. So do any atheists who want to teach “courage” or “heroism” or “ambition” or “humility” yet use these things against their Creator.

Fascinating and stimulating reading, both this and all the comments below it.

I have been asked to conduct communion at our church. I felt stirred earlier in the day to speak of Christ the conquering Captain of the Host, the valiant hero who came to rescue us from the oppressor…everything you’ve said above about Him. As Moses sang in Exodus 15 “The Lord is a Man of War..”

In regard to all the attempts to portray God as the Bad Guy, I’ve noticed that it takes a lot of hard work explaining away the obvious, a lot of glossing over experience and evidence to the contrary etc..

I have come to the conclusion that as “God has put eternity in the heart of every man”, the attempt to deny that sense of eternity; and the heroic, redemptive nature of our God, stems from a desperate desire to be captains of our own destiny, to do what WE want.

Imagination is a gift from God, but it can be used for evil as well as good. It is possible to try to shape the public’s imagination to denigrate and vilify God, but ultimately it doesn’t fool anyone but those who find Divine Truth and the healthy righteousness of God a real inconvenience. Admittedly and sadly, there’s plenty of those out there. But even non-academics like me can see through it.

The Golden Compass was a box-office flop as compared to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Should we be surprised? Was it because the production was much better? I don’t think so.

It’s like the research that was done on Japanese children:

“For example, researchers at Oxford University (at which Richard Dawkins himself was until recently the holder of the Charles Simony Chair in the Public Understanding of Science) have earlier reported finding children who, when questioned, express their understanding that there is a Creator, without having had any such instruction from parents or teachers.”

So it came, not as a surprise to me, but as an “Ahah!” moment when I rediscovered my innate conviction that Jesus is My Hero, My Rescuer, My Redeemer. In every story I’ve read where there has been a larger-than-life hero, I can see Jesus. Why? Because, in a sense, Jesus IS larger than this hum-drum, fallen existence that we call life.

In the light of these comments, can I have some comments about this short story I wrote, please.

It’s called “The Hunter”, and it’s at this link:

https://faithwriters.com/article-details.php?id=77995