It’s Alive!

One of the most common tropes in science fiction is the creation of some sort of autonomous being. With the invention of the computer, sentient r obots and artificial intelligence pop up quite frequently, but even more than a century ago, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein played with the notion of life being created from non-life (or in that case, dead flesh).

obots and artificial intelligence pop up quite frequently, but even more than a century ago, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein played with the notion of life being created from non-life (or in that case, dead flesh).

Another trope that often follows: it rarely ends well.

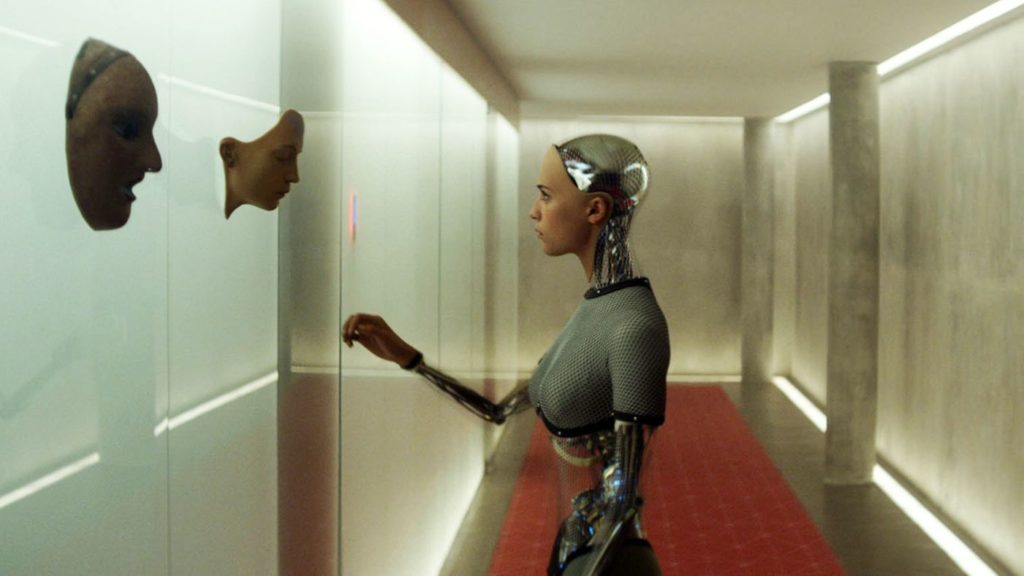

I recently watched Alex Garland’s emotional android film Ex Machina. It is a brooding, philosophical tale, but if you’ve seen the trailers, you know things get weird and violent. It was a bit of an unsettling film and it definitely engaged my mind and heart, though it is not the masterpiece it thinks it is. This article is not a film review so I’ll stick to the main point. In the movie, a hip, bearded CEO of a Google-like company creates an android with human-like thoughts, emotions, and the ability to communicate. A worker from the software company is brought in to “test” the robot to see if he can come to think of it as more than a robot. By extrapolation, that means if a human can regard a machine as human on some level, then that’s what it is.

This idea was explored i n Isaac Asimov’s The Bicentennial Man (let’s just pretend that the Robin Williams film adaptation never existed). In that story, a robot goes to court to fight for its recognition as a human. This is one example of AI sci-fi where robots aren’t trying to kill us. Hollywood apparently wasn’t satisfied and took Asimov’s I, Robot series (of which The Bicentennial Man is a part) and made a movie about seemingly innocuous robots ganging up on Will Smith. Literary and cinematic science fiction is filled with similar stories and plots. To borrow from Jeff Goldblum: God creates man. Man destroys God. Man creates robots. Robots destroy man.

n Isaac Asimov’s The Bicentennial Man (let’s just pretend that the Robin Williams film adaptation never existed). In that story, a robot goes to court to fight for its recognition as a human. This is one example of AI sci-fi where robots aren’t trying to kill us. Hollywood apparently wasn’t satisfied and took Asimov’s I, Robot series (of which The Bicentennial Man is a part) and made a movie about seemingly innocuous robots ganging up on Will Smith. Literary and cinematic science fiction is filled with similar stories and plots. To borrow from Jeff Goldblum: God creates man. Man destroys God. Man creates robots. Robots destroy man.

The creation of life is the pinnacle of scientific ambition. To create life is to be God in some sense, and wanting to be like God has been humanity’s downfall since the Garden. In the largely atheistic realm of science fiction, one would expect to see these fantasies cultivated and applauded, since it is only possible in the realm of imagination anyway. So why all the bummers, dude?

I won’t pretend to have the answer, but I suspect that deep in our souls, we know that it is a goal that we will never reach. We have tried and failed on numerous occasions, and even our grandest attempts have been quite comical (a tower to Heaven? Really?). We are confronted with our own mortality and frailty on a daily basis, and being God is not a job for lightweights. The staggering responsibility of such a title terrifies us, despite how much we may crave it.

We also know how little power we truly possess, and this is why it is so easy for our creations to turn on us in books and movies. We have seen it in our world already – nuclear weapons that could annihilate all life on Earth stand ready for launch at the push of a button. We are totally in over our heads and we know it. What makes us think we could control intelligent machines that are already physically superior to us? Skynet and Judgment Day don’t seem like such far-fetched ideas anymore.

Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, and other prominent geniuses have speculated on the real possibility of “killer AI.” They have the foresight to see what Hollywood toys with. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t try to create intelligent programs and machines that can mimic emotions, but that all it will ever be: mimicry. Will Smith’s jaded policeman character in I, Robot mocks the sentient robots as being “nothing but lights and clockwork… An imitation of life.”

Only God can truly create life. And unlike us, He has nothing to fear from His creation. That is another characteristic that makes Him God. We can coddle ourselves with self-affirmations, but in our hearts, we know the truth. It already bubbles up to the surface in our art, which is often the place where we find the truths that we don’t like to admit.

Well, humans could be said to be machines made of meat, with feelings and thoughts made by chemical reactions. THE UNCANNY VALLEY ALSO LOOKS INTO YOU.

This is all a way of poking around what it means to be human. Or, in contrast, what it means to be inhuman, superhuman, or just nonhuman. That’s an idea I want to explore, whether and what it would take for someone human to turn in/super/nonhuman, or all at once. Or what/how much would remain human despite manipulation and tinkering. Except I feel like I need to get my master’s in psychology to do it to my satisfaction.

It’s the arrogance that irks me. In I, Robot, the sagely doctor who created the “Three Laws” declares, “One day they’ll have secrets; one day they’ll have dreams.” This is just self-aggrandizing wankery. Our greatest masterpieces will always be a cheap colorless copy of the real thing. That’s not to say we shouldn’t try, but our motivation should be to glorify the Creator as creations in His image, not to say, “I don’t need You anymore; I can do it myself.”

[flaps hands mystically] But whaaaaat is a dream? Whaaaat is a secret?