“I Don’t Read Fiction,” She Said, Disapproving.

At a book signing last spring, a woman speaking with the author beside me kept glancing my way with a sort of sour uncertainty. In a long-sleeved blouse, long denim skirt, and with her gray hair in a bun, she had the prim-and-proper look down pat.

Since I live at the edge of the largest Old-Order Amish community in the world, I often see women in ultra-conservative garb. But they don’t usually look at me askance, as this woman did. I guessed it was the cover image on the sci-fi books on my table that made her nervous.

Since I live at the edge of the largest Old-Order Amish community in the world, I often see women in ultra-conservative garb. But they don’t usually look at me askance, as this woman did. I guessed it was the cover image on the sci-fi books on my table that made her nervous.

Next time her furtive gaze flitted my way, I smiled, trying to ease her discomfort. She seemed to relax a bit, perhaps thinking I might not be as dangerous as she feared. The author next to me noticed our cautious interaction and introduced me. “This is Yvonne. She and I go to the same church.”

Turns out the woman was her sister-in-law. Apparently the church connection reassured her that I was safe to talk to. But to make sure we’d have no misunderstandings, she told me with self-righteous conviction, “I don’t read fiction.”

I’ve heard that before. Some see make-believe in any form as childish, and novels, much like playing cards, give the devil entrance to the heart and mind. Still hoping to show myself a benign entity, I shrugged. “That’s okay. Not everyone likes that sort of thing.”

After that, she became chatty. (It probably helped that her sister-in-law was in close proximity in case she needed back-up.) I don’t recall what roads our conversation rambled along, but somehow we came to the subject of romance novels. She smiled as if discussing a friend. “That’s what I read. Romances.”

I can’t tell you what my expression said in response, nor do I remember what I verbalized. What I thought was, “And that’s not fiction?”

Let’s give the lady the benefit of the doubt. When she said, “I don’t read fiction,” she probably meant she doesn’t read science fiction. But few things fit the criteria of literary fantasy more solidly than romance novels. Like with reality TV — you’d find more reality at Disney World.

Or so I presume; I’ve never been to Disney World. But I’m guessing there’s sufficient real-life high-level logistics, mechanics, engineering, and business acumen going on there to boggle the mind if we knew the half of it.

One might ask, if real life is so interesting, why bother with fiction? One answer: facts are less dry and easier to digest when put into story form. We learn more about history from historical novels (assuming they accurately portray the facts) or novel-like memoirs than from the best textbook. Scientific concepts? Put them in a story where the character learns about them, and I’m fascinated; hand me an academic paper, and my eyes glaze over.

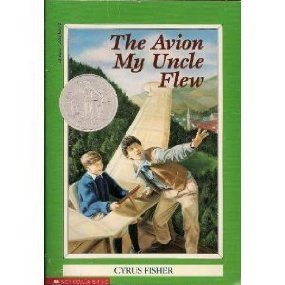

How about foreign language? When I was in elementary school, I read a book called The Avion My Uncle Flew. It was a story  about a boy whose parents sent him to live with his uncle in France. I don’t remember a thing about the story, except that during his stay, the boy learns some basic conversational French, and the reader learns along with him. The last chapter is a letter the boy wrote to his parents entirely in French, and, thanks to the education gained during the course of the book, the reader can read every word of it. What a fabulous way to learn! (Note: since the book gave no auditory clues, the reader would need additional help with the pronunciation. For instance, I thought the French word for it is [c’est] was pronounced kest.)

about a boy whose parents sent him to live with his uncle in France. I don’t remember a thing about the story, except that during his stay, the boy learns some basic conversational French, and the reader learns along with him. The last chapter is a letter the boy wrote to his parents entirely in French, and, thanks to the education gained during the course of the book, the reader can read every word of it. What a fabulous way to learn! (Note: since the book gave no auditory clues, the reader would need additional help with the pronunciation. For instance, I thought the French word for it is [c’est] was pronounced kest.)

To my mind, the mark of a good book has little to do with its genre. Though I write Christian speculative fiction, I’ve never considered the typical Christian novel appealing, nor would I say science fiction and fantasy are my favorite genres. I like a book I can learn from; something that challenges me to view the world from a different perspective; a story that takes me somewhere I’ve never been before.

But speculative fiction’s pretty “out there.” What can we possible learn from it? In my opinion, plenty. Just as you might learn a little history from historicals, you might learn a little science from hard sci-fi. But more than that, spec-fic, whether or not it’s written from the Christian perspective, is the perfect medium for showcasing the human condition—our frailties and limitations, our varied attempts to redeem ourselves, our ceaseless repetition of the sins of our fathers.

It’s been said that good sci-fi is all about big ideas; to properly enjoy it, your brain must be engaged. I’d say that applies to all good speculative fiction, not just sci-fi. While the average mystery, thriller—and yes, even romance—deals with immediate issues and  up-close crises, speculative fiction pans across the big-picture panorama. Discarding the trappings of culture and tradition, it lets us see why mankind does what he does—and how, despite negative consequences, he does it again and again. Sometimes it illustrates the futility of humanism; sometimes it shows that our only hope comes from beyond ourselves (whether that “beyond” is spiritual or extra-terrestrial). It asks serious questions, and doesn’t always answer them. Even when the immediate crisis is resolved at the end of the tale, the bigger issues often aren’t.

up-close crises, speculative fiction pans across the big-picture panorama. Discarding the trappings of culture and tradition, it lets us see why mankind does what he does—and how, despite negative consequences, he does it again and again. Sometimes it illustrates the futility of humanism; sometimes it shows that our only hope comes from beyond ourselves (whether that “beyond” is spiritual or extra-terrestrial). It asks serious questions, and doesn’t always answer them. Even when the immediate crisis is resolved at the end of the tale, the bigger issues often aren’t.

I think that’s why speculative fiction has existed, in one form or another, since the beginning (as I observed awhile back in a post about epic poems). And that’s why I expect it won’t be going away any time soon. The format, the delivery, and plot lines change. But the deeper meaning that fuels it is eternal.

“But more than that, spec-fic, whether or not it’s written from the Christian perspective, is the perfect medium for showcasing the human condition—our frailties and limitations, our varied attempts to redeem ourselves, our ceaseless repetition of the sins of our fathers.”

YES! I cannot tell you how many times I have said the same thing to Christians who right away hold their fingers crossed in front of them to ward off the very idea of reading speculative fiction.

It is the ideal place to explore human nature, and all its strength and frailty in situations that do not allow us to pollute the experience with our own personal or historical baggage.

Hey, if I can ponder what life would be like on this planet, and what humans would be capable of, if our thin veneer of civility were shattered AND have a few triffids thrown into the mix, I’M GAME!

Why not?

I always tell folks that the very first facet of the nature of God we learn in the Scriptures is that He is a creator. And so we, as His children, ought to exhibit the very same facet without apology! As our Father created the universe (universes?) with such creative freedom, why don’t we mimic Him and create our own?

Great article! Thanks.

Steve Crespo (fromnothingcomics.com)

Thank you, Steve – bring on the triffids!

Agreed, and very well said. However, I think this needs a little qualification:

I think fantasy and science fiction do contain both culture and tradition in their story-worlds, but they are used more deliberately, in a different way. Speculative fiction can specifically select elements of culture and tradition to scrutinize in an environment where the strengths or failings can be seen more clearly.

You’re right, Bainespal. Spec fic does, indeed, contain culture and tradition in its story worlds, but it’s usually different from what we see in our everyday worlds; it removes us from the familiar, which we too often take for granted and can’t see for looking, and puts us in a new world where we can see it from a fresh perspective. This sometimes helps us see the familiar more clearly than we ever have before.

Oh goodness! I laughed. “I don’t read fiction.” And yes, I shall take your advice and give her the benefit of the doubt. Major props to you for handling that discussion with grace. Some wonderful nuggets here. Thank you so much for sharing.

Yeah….romance novels. In one of my classes today we discussed a quote from one of our textbooks about “levels” of truth, which I condensed to “logical” and “emotional”–head and heart, basically. A story set entirely in one sagging apartment might be truthful in the sense that events may happen in that process, but if the emotions are off, it ruins the whole story. I tend to prefer my emotional truths a little larger than life.