‘I Do Not Read Fluff!’

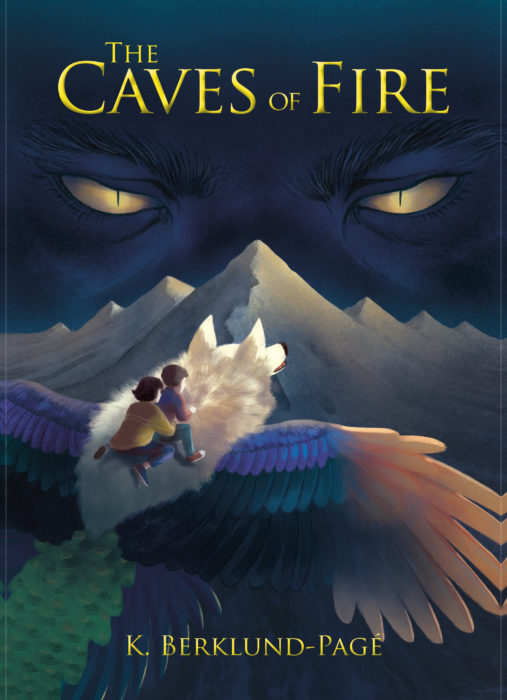

I was signing books at a Christian conference when a woman wandered by and picked up my novel.

“What’s it about?” she asked.

“It’s a fantasy adventure for ages ten and up,” I replied.

She hesitated. “So, it’s—it’s fiction?”

I smiled and nodded, ready to continue the conversation.

It didn’t happen.

“I do not read fluff!” She flung the book back onto the table and marched away.

I was stunned.

If she’d said, “I’m not a fiction person,” or “I’m not into fantasy,” I would have understood.

But she didn’t. She said that she doesn’t read “fluff.”

I suppose I could have asked her to define fluff, but my guess is that her answer would have confirmed what the editor of a Christian publishing house told me: Many Christians believe that reading fiction is a waste of time.

That thought saddens me. All fiction is a waste of time? Some is, for sure, and we each have our own list of what’s not good for us to read, but all fiction is a waste of time. Useless? Fluff? Wow.

Eugene Petersen didn’t think so. Petersen was a pastor for many years, then a seminary professor. He’s the author of multiple non-fiction books. In his introduction to Exodus, he said,

It is significant that God does not present us with salvation in the form of an abstract truth, or a precise definition or a catchy slogan, but as story. Exodus draws us into a story with plot and characters, which is to say, with design and personal relationships. Story is an invitation to participate, first through our imagination and then, if we will, by faith—with our total lives in response to God.

In an interview with Mars Hill, he said that if he were to start a seminary, the students would spend the first two years studying literature:

Even now, in all my courses, students read poetry and novels…The importance of poetry and novels is that the Christian life involves the use of the imagination, after all, we are dealing with the invisible. And, imagination is our training in dealing with the invisible, making connections, looking for plot and character. I don’t want to do away with or denigrate theology or exegesis, but our primary allies in this business are the artists. I want literature to be on par with those other things. They need to be brought in as full partners in this whole business. The arts reflect where we live, we live in narrative, we live in story. We don’t live as exegetes.1

If I had it to do over again, I’d lead off by telling my fluff-hater that my story is about friendship. About choices. That our choices have weight. That we need each other. How can that be fluff?

I’d tell her that I write for the 10 and up crowd because there are questions from that age that I still haven’t finished sorting out. Things like what I believe and why. Questions about belonging. At age fifteen, I was dropped into a foreign culture where I didn’t speak the language. What does it mean to belong in that context? How do you even begin? The question of what it means to belong has continued as I’ve lived almost all of my adult life in a language and culture that is not mine. Or is mine by adoption. Perhaps that’s why I wrote a portal fantasy. Like the characters in those stories, I was thrust into a new world and had to muddle through as best I could.

If the woman gave me the chance, I’d go on to tell her about some of the fiction that has influenced, challenged and shaped me.

Till We Have Faces by C. S. Lewis would be at the top of the list. I read it for the first time in my 20’s and have read it seven or eight times since then. It has shaped my understanding and experience of God more than any other book outside the Bible.

The Earthsea Trilogy by Ursula K. Le Guin was a friend when my husband and I were going through a difficult situation in our faith community. The images and metaphors in Le Guin’s stories didn’t solve any of our problems, but they helped me understand and move forward with hope.

The list could go on, but I’ll stop there and open it up to comments. I would love to hear how fiction has helped, encouraged, and shaped you.

- Michael J. Cusick, “A Conversation with Eugene Peterson,” LeaderU.com. ↩

Hm…some people might take the standpoint that all fiction is ‘fluff’ and that nonfiction isn’t. But if the info in a nonfiction book isn’t going to be used by the person reading it(which is possible) that would mean that the nonfiction book is ‘fluff’ for that person. But, it’s hard to know for sure whether or not the info in the nonfiction book will indeed never be used, so we read them anyway if the topic is interesting enough. We often view that as a good thing(educating ourselves on a topic even if it has no immediate use)

The same can be true of fiction, though. We never know if the story presented within will have a lasting impact on us or not, but we read anyway.

Even if reading fiction was fluff, though, writing it certainly isn’t. It’s very useful for learning to articulate ideas, and it’s often motivation for authors to do research.

The appropriate response to incite equal offense might be, “Because you’re a white-washed Pharisee destined for a permanent vacation in the heart of a volcano.” With a smile, of course…

Kidding, no one should say that (probably). I’m just so sick of that prideful, hateful attitude, and people who call themselves Christians getting away with wielding it like a weapon of the Almighty God.

LOL. Afterwards, I thought that I could have answered, “I totally agree with you. I don’t read fluff either.”

At least she said *she* didn’t read fluff, rather than claiming Christians shouldn’t. People are allowed their personal reading preferences. It’s unfortunate she had to be rude about it, though.

Sad that this was her response. As a kid who often felt alone, fiction showed me that I wasn’t. I would’ve been in a very bad place, if not dead if not for the lessons learned in “fluff” books.

Without knowing anything else about the exchange, I’d have guessed she may have called it “fluff” because it was a book for children, so likely she considered it something she wouldn’t want to read.

I guess they may be out there somewhere, but personally I’ve not met any Christians who think that reading fiction is a waste of time.

Even taking all the things you can learn from fiction away, there have been lots of studies that show that reading fiction makes one more empathetic, which is a helpful trait to cultivate as Christians to better help them share love, mercy, and charity.

Jesus taught by parables, which are fiction.

And some books have given me ideas which helped maintain my faith when under attack. Such as Puddleglum’s determination, in Lewis’ The Silver Chair, to live as much like a Narnian as he could even if Narnia doesn’t exist — which has at times been my default position as a Christian. Because even if Christ were fictional, he is still better than anything the mundane world has to offer.

I said that to a lady (that Jesus taught by parables, which are fiction), and that doorknob of a human had the gall to say, “Because they were stupid people, and that’s the only way he could talk to them.”

I was dumbstruck. It’s the opposite of Jesus’ stated reason for using parables (to obfuscate the truth, keep it from the unfaithful, and to have it pierce the hearts of those who had faith).