Hope And Hopelessness In Speculative Fiction

Modern literature takes insanity as its centre. Therefore, it loses the interest even of insanity. A lunatic is not startling to himself, because he is quite serious; that is what makes him a lunatic. A man who thinks he is a piece of glass is to himself as dull as a piece of glass. A man who thinks he is a chicken is to himself as common as a chicken. It is only sanity that can see even a wild poetry in insanity. Therefore, these wise old tales made the hero ordinary and the tale extraordinary. But you have made the hero extraordinary and the tale ordinary—so ordinary—oh, so very ordinary. (from Tremendous Trifles)

After the horrific terrorist attacks in Paris this past week, we might think that modern fiction has it right: the world is gray, until it turns black. And what’s so bad with gray? Ordinary doesn’t sound so bad.

But Chesterton saw in speculative fiction something greater: in “fairy tales” hope ascends.

For the devils, alas, we have always believed in. The hopeful element in the universe has in modern times continually been denied and reasserted; but the hopeless element has never for a moment been denied…. The greatest of purely modern poets summed up the really modern attitude in that fine Agnostic line—“There may be Heaven; there must be Hell.”

The gloomy view of the universe has been a continuous tradition; and the new types of spiritual investigation or conjecture all begin by being gloomy. A little while ago men believed in no spirits. Now they are beginning rather slowly to believe in rather slow spirits. (from Tremendous Trifles)

I find Chesterton’s perception of “modern fiction”—stories written in a realistic style nearly a hundred years ago—eerily similar to stories written in a realistic style today. When the imagination is separated from spiritual reality, it seems to stall on the bleak and the horrible.

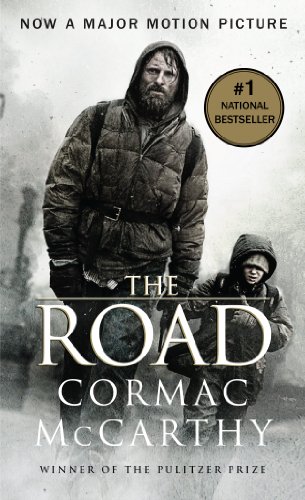

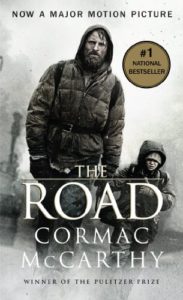

Any number of stories illustrate this, none less so than The Road by Cormac McCarthy, a post-apocalyptic novel (released in 2006 and made into a movie in 2009) about survival in which the protagonists determine they are the good guys. When the boy’s father dies, his hope then hinges on his father’s statement that after his death, his son can pray to him, and on the idea that the people he joins are also good guys.

Any number of stories illustrate this, none less so than The Road by Cormac McCarthy, a post-apocalyptic novel (released in 2006 and made into a movie in 2009) about survival in which the protagonists determine they are the good guys. When the boy’s father dies, his hope then hinges on his father’s statement that after his death, his son can pray to him, and on the idea that the people he joins are also good guys.

Survive. Try to be a good guy. And die.

Those facts fit with what we know. Life is … not as exciting as we wish, and more horrible than we can bear. In short, the consequences of our actions and choices are more dire than we expect. Then, awaiting at the end is … the end.

In contrast, the Christian sees beyond the here and now. Because of our Biblical worldview we understand that spiritual realities (the eternal) are more real than physical realities (the finite and temporal). The here and now is the prelude, not the main act, and most definitely not the final act.

When we grasp spiritual realities, whatever happens in space and time takes on a different characteristic because with it comes Promise. And Hope. The life we live is abundant life!

The one point I disagree with Chesterton about when it comes to story is his view of the protagonist of a fairy tale:

As I see it, a Biblical worldview says the soul is “sick and screaming,” but the world also has gone mad and at its best appears dull.Realism means that the world is dull and full of routine, but that the soul is sick and screaming. The problem of the fairy tale is—what will a healthy man do with a fantastic world? The problem of the modern novel is—what will a madman do with a dull world? In the fairy tales the cosmos goes mad; but the hero does not go mad. In the modern novels the hero is mad before the book begins, and suffers from the harsh steadiness and cruel sanity of the cosmos. (from Tremendous Trifles)

So the problem a fantasy deals with is this: what does a soul, sick and screaming, do in a world gone mad? Certainly painting it in those terms, such a story does not appear to traffic in hope.

But I suggest the solution to the problem offers the truest hope—such a soul can do noting to right the world. He must trust in Someone greater than himself.

The idea that the soul is healthy, I think, is perhaps the cruelest of concepts, one that leaves the reader, knowing himself to be less than whole, not only wanting but isolated, since he concludes that he alone is not healthy.

As I see it, then, there are two kinds of stories that lead to hopelessness—ones that are realistic about the physical world but not about the spiritual, and ones that falsely infuse hope by suggesting a person can become a healthy soul of his own accord, or that society, by working together, can achieve the dream.

In a world that feels increasingly unsafe, a speculative writer has the awesome task of painting the picture of spiritual victory and eternal safety. False promises won’t do. Speculative fiction needs to infuse readers with the truth about the here and now but also about the hereafter.

What books do you think successfully confront the truths of this world in light of God’s eternal truth?

Minus some revision, this article first appeared here in September 2011.