Guest Blog: Mike Duran

Is “Christian Speculative Fiction” an Oxymoron?

By Mike Duran

The label “Christian Speculative Fiction” is an oxymoron. At least, that’s one of my going theories.

The label “Christian Speculative Fiction” is an oxymoron. At least, that’s one of my going theories.

Believers who enjoy speculative fiction often bemoan the lack of such titles in Christian outlets. While Borders and Barnes and Noble contain aisles of horror, science fiction, graphic novels, and fantasy, spec titles comprise a relatively minuscule portion of the religious fiction market. Why is this?

I have several going theories. The one I’d like to float to the Spec Faith crowd is this: To many believers, speculation, especially when it involves theology, is potentially un-Christian.

In 1988, Martin Scorsese’s film The Last Temptation of Christ opened to protests, boycotts and denunciations. It’s based on Nikos Kazantzakis’ controversial book, the central thesis of which is that Jesus, while free from sin, was still subject to every form of temptation that humans face. Along the way, the author explores what it might have been like for Jesus to undergo the temptations of the flesh. Despite the fact that Scripture tells us Christ was “in all points tempted as we are” (Heb. 4:15), the subject matter proved too offensive for many Christians. Note, this is not necessarily an endorsement of either the book or the film. Nevertheless, I think The Last Temptation of Christ controversy illustrates the inherent problems Christians face in approaching speculative titles.

At the heart of the Christian religion is a well-defined set of articles, a non-negotiable series of doctrines. To question these things is to undermine one’s own faith (see: heretic). On the other hand, “questioning things” is at the heart of the speculative genre. Speculative fiction is best when it “speculates” — when it tweaks reality, reinvents the rules, rewrites histories, and tinkers with the facts. In this way, speculative fiction, by its very nature, grates against the core of Christianity, which states that some things are beyond the pale of speculation.

Because of this, it is not uncommon to see Christian reviewers questioning the theology of a work of Christian fiction. Why? Because theology is at the heart of what defines Christian fiction.

I recently read the following on the website of an aspiring Christian novelist. The author described / defended their story thus:

Although based on a true Biblical account, this is a fictional story. I have attempted to carefully craft the plot and shape my speculation without contradicting the Bible anywhere. If you find any such contradiction, or are offended in any way by the artistic liberties I have taken, I gladly defer to the account given in the book of Genesis [emphasis mine].

This author, perhaps unintentionally, reveals the rub. We must “shape [our] speculation without contradicting the Bible anywhere.” In other words, there’s a line between “artistic liberty” and “biblical truth.” Problem is, does anyone know where that line is? Did Nikos Kazantzakis cross that line? Did Paul Young cross that line in The Shack? Did C.S. Lewis cross that line in The Great Divorce?

The tension between Christian theology and speculative fiction is always on the believer’s end. Atheists and postmodernists are not tethered to dogma in the way that we are. This is not to suggest that they are unrestricted by their own worldview, but that the boundaries of their worldview are a lot more expansive than ours. To the relativist, history is free to be re-written, and morality is up for grabs. Conversely, we walk a “narrow road.” And, whether good or bad, it shows in our fiction.

Perhaps this is a good thing. Maybe we should be caretakers for the “ancient boundaries.” Perhaps there are subjects and worlds and beliefs that should be off-limits to the Christian author. The question I’m posing is whether or not this is why Christian speculative fiction lags. Is there an inherent incongruence between Christian theology and speculative fiction? Do we allow our theology to stifle our speculation or fuel it? Does our theology make the world a bigger place, or a smaller one? Does our theology create more possible worlds, or less?

Anyway, that’s one of my going theories. I’d love to hear some of your thoughts.

– – –

Mike Duran has lived in Southern California his entire life. He and his wife Lisa were married in 1980, and have raised four children, all of whom live in SoCal. He has chronicled his conversion to Christianity in a series of blog posts entitled “The Hard Road Home” at his blog, Decompose.

Mike Duran has lived in Southern California his entire life. He and his wife Lisa were married in 1980, and have raised four children, all of whom live in SoCal. He has chronicled his conversion to Christianity in a series of blog posts entitled “The Hard Road Home” at his blog, Decompose.

A former pastor, Mike now works in construction and is a freelance writer whose short stories, essays, and commentary have appeared in Relief Journal, Relevant Online, Novel Journey, Rue Morgue magazine, and other print and digital outlets.

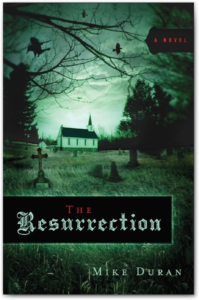

His debut novel, The Resurrection (Charisma House), releases this month.

“The question I’m posing is whether or not this is why Christian speculative fiction lags. Is there an inherent incongruence between Christian theology and speculative fiction? Do we allow our theology to stifle our speculation or fuel it? Does our theology make the world a bigger place, or a smaller one? Does our theology create more possible worlds, or less?”

Mike, in answer to this, I’ll happily point you (and others) to the writing of last week’s guest blogger, Marc Schooley. Marc’s possibly the most theologically grounded mind I’ve encountered anywhere in Christian fiction, and yet his speculative creativity is off the charts. Rather than being limited by theology, his work is driven by it. He’s the writer who definitively answered these questions for me as a reader, and did so in a way that deepens and affirms both my faith and my sense of what it means to be a creative person.

C.L., thanks for referencing that article. However, I don’t think it really addressed the issue I’m talking about. I’m not disputing that Christians can’t be creative, but that their Christianity tends to “cap” how far they can go. The even bigger question (which Marc’s post also does not answer), is “Is this ‘speculative cap’ one of the reasons why Christian spec-fic has little traction in the Christian market?” Thanks for commenting!

Sorry, Mike, I should’ve been more clear–late-night posting. Marc’s two novels, not the article, were what I had in view. As a fiction author, Marc has no cap on his speculative nature, but remains intensely grounded in theology.

I agree fully on the point that the Christian market is made up of readers who avoid what has even the potential to offend their deepest beliefs. It’s human nature to do so.

The same’s true within other markets, which is why GLBT fiction has its own niche too. Life bruises our sense of psychological safety and well-being enough on a day-to-day basis that it’s natural to seek to eliminate that feeling from our leisure pursuits.

It may be better to look at speculative Christian fiction as a separate market altogether from CBA fiction, even if Christian speculative publishing comes under the CBA publishing banner.

Oops that was meant to be a reply to the author who claimed at the heart of our religion are a set of facts that we are not “allowed” to question. He seemed to forget that we actually have a Person who is Truth at the heart of our “religion.”

Derek, as the commentors below mention, I think you missed my point. I am coming from the position that Christians should be wildly imaginative. I also happen to believe that the Christian market has conjured (whether through theological interpretation or demographics) lots of restrictions on how far a Christian is permitted to go. Thanks for commenting! And I hope you continue to return to this site.

I apologize Mike – I guess I missed the point you were making. I’ll reread and be less hasty with my comments in the future…

Hi, Derek, thanks for stopping by. Spec Faith is a collaborative blog and we have reserved Friday’s for guests. The thoughts and opinions of each contributor and each guest belongs to each individual. We make no attempt to coordinate a viewpoint on different issues and we encourage discussion. If you visit today’s guest at Decompose, his own writer site, I think you’ll find that he does not fall into the category of “rule keeper.” Instead, I believe he was suggesting that there is a (large) segment of Christendom that may fall under that heading, which explains, in his mind, why Christian speculative fiction isn’t a big seller.

Hope that helps you know whether or not you want to visit our site again (I hope you do).

Becky

Derek, I took another look at Mike’s article. I’m guessing you were reacting to this:

I’d have to say that doesn’t seem like anything more than a recognition that certain things define what it means to be a Christian (just like certain things define what it means to be Canadian or female or Steeler fan). I’d say that the “well-defined set of articles” has as its chief point, entering into a relationship with God through His Son Jesus Christ.

Becky

Adding to Becky’s thoughts, Derek: though one’s faith is not in mere facts, one also cannot have a relationship with any person, be it family member, friend, husband or wife, or Christ Himself, without knowing or seeking to know the true Facts, characteristics, nature, of that person. For His glory and our good, He has indeed revealed much about Himself to us in the Word. To accept and delight in those doctrines/facts, because they allow us to get closer to Him and to know Him better and become more like Him, glorifies God.

My view: as long as we do not speculate beyond the metanarrative of Scripture — God is awesome, majestic, people are not, but God saves anyway — we are free to speculate, using what/if questions about the minor details. Example: what if God waited until a steampunk version of the 17th century to call out an Old Covenant people? And of course, Other-worlds or parallel dimensions, where other “rules” vary.

Thanks for a great column, Mike. And Derek, speaking for me and not for you, I know that sometimes I can be a bit sensitive to someone who is either all-“doctrine”-and-no-relationship (which ignores crucial doctrines anyway!), or else all-“relationship”-and-no-doctrine (which isn’t a real relationship anyway). From what I’ve seen of Mike, he’s not that-a-way. And sometimes it takes a while to form a “relationship” with someone, even over the internet, learning more “doctrine” about them, before we know they indeed believe in both doctrine and relationship.

Okay thanks everyone for the gracious responses…I guess I was carrying over some frustration at hearing CS Lewis being called a heretic by a complete spiritual hack.

@ E. Steven Burnett – I completely agree with the role of doctrine and relationship that you stated…I agree “all doctrine and no relationship” ignores the most crucial doctrines. Good stuff..

the CS Lewis thing was in another post…not this one

I’m thinking there are two sides to this. One is that there are core doctrines which to be “Christian” one has to uphold. To speculate on those to the point of changing them goes too far because it results in a refutation of who Christ is. That is the real issue behind The Last Temptation. It presented a Christ which made Him unable to save mankind by sinning.

But there is still plenty of room for speculating things. Yes, there are boundaries if it is to be a Christian worldview or have Christian morals. Not to say individual characters can’t violate those, but the story as a whole either needs to uphold those in a positive way, or highlight the horrors of not following them. But there is plenty of room for “what if God did this instead…” without turning the work into something non-Christian, as TLT did.

The other side is that for as many groups as there are out there, there are nearly as many opinions on what theology should be. The more major the doctrine or belief, the less that is, but even there you find differences of opinion and thought.

So there are those who do have “rules” and check-boxes, and anything outside that little window is wrong, sin, or simply not compatible–avoid. So you have those who say that since fantasy is about unreal things that God didn’t create, they are a lie, and Christians are commanded not to lie, so you don’t write or read fantasy.

But there are a lot more Christians who do not think in that manner, whose theology doesn’t prevent them from being creative. Not creative with the theology, mind you, but with the story, world-rules, characters, and other bits of info that make up the whole backdrop upon which such a theology might be played out. I think that is why other worlds are so frequent in fantasy, and even science fiction of the space opera kind, is because in this world, it is easy to step on a theological toe, or take on a subject that one can cross a line on. If I have Christ sin, that would rightly get Christian wrath thrown at me. If I have a supposed redeemer on another world sin, that won’t get me thrown out, as they wouldn’t look at the two as one and the same.

But I do think, Mike, you are at least partially correct. There is a strand within Christianity that thinks the only thing worthwhile reading is non-fiction devotions, articles on self-help, Bible study, etc. Those are certainly good, but the assumption that a good fantasy story is a waste of time is where the problem lies. Sometimes, such a story is the only way someone is going to “see” the light, which is precisely why Christ told parables instead of giving a bullet point sermons.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Timothy Stone, Speculative Faith. Speculative Faith said: Debut novelist Mike Duran (@cerebralgrump ): "Christian speculative fiction" an oxymoron? On #SpecFaith: http://bit.ly/eCcdsV […]

[…] yesterday’s post, Becky Miller responded to Mike Duran’s guest post (“Is Christian Speculative Fiction an Oxymoron?“) by writing, In fact I’m saying “speculative fiction” is incongruous. Novelists of any […]

Speculative Fiction has more to do with labeling than speculating. It goes to the genesis and history of genre terminology.

In the beginning, you had Science Fiction (which is really a bad term, but not as bad as Sci-Fi if you’re a ‘serious’ writer). It gets worse when you shorten things to the logical acronym, SF (which for many calls to mind ‘San Francisco,’ which, to be fair, predates Hugo Gernsback and his Scientifiction). Furthermore, we had many great authors who wrote both Science Fiction and Fantasy (and others, like Roger Zelazny, who intentionally blurred the lines between the two).

And thus was Speculative Fiction born. It was a smarter SF acronym, it incorporated both Science Fiction and Fantasy, and it sounded more literary than Sci-Fi. Whether Speculative Fiction did any ‘speculation’ was rather an afterthought. Because of the progressive thought that went into the term, I suspect the people that started using it were less concerned that ‘speculative’ and ‘fiction’ when paired together would look to readers coming after them as an oxymoron. The term had a purpose then, and we would do well not to overthink it.

There’s more about the genesis of SF (in all its forms) by author Robert Sawyer:

* http://www.examiner.com/science-fiction-in-national/robert-j-sawyer-interview-on-sci-fi-sf-speculative-fiction-pt-1

* http://www.examiner.com/science-fiction-in-national/robert-j-sawyer-interview-on-sci-fi-sf-speculative-fiction-pt-2

[…] a recent article at Speculative Faith, in response to Mike Duran’s guest blog there, I concluded with this: As I see it, all the world, and all the pretend worlds we can […]