Fighting Man-Centered Monsters In Christian Fantasy

It was like New Year’s Day came early, with reactions rolling one by one across time zones — only instead of being at midnight, the updates from friends came at about two hours past that, and instead of “Happy New Year,” they were expressions of horror, misery, woe and pain.

They were limited to those who had seen The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in theaters at the midnight showing.

“I officially do not want any more Narnia movies to be made,” lamented one friend, a longtime Narnia fan. “I am not even sure I’ll go see the next one.” I told him that if I were a drinking man, now might even be a good time for us to go out and get drunk.

The movie wasn’t all bad. Reepicheep and Eustace were perfect, near-exact images of their equivalents in C.S. Lewis’s third Chronicle of Narnia. Aslan the great Lion was done very well.

But the film’s addition of an Evil Green Mist™ to fight not only itself fought against the book’s themes of seeking honor, adventure and Aslan’s Country, it made little sense as a storyline. The threat was too vague and unsourced. How does it connect to the Dark Island? Why “feed” it captives and on what basis? How does it have teleporting powers? Where were the Mist’s captives — hypnotized? asleep? some kind of suspended animation? And just how, exactly, do the seven magic swords of Aslan provide power to defeat the Mist?

I won’t complain more about the Green Mist™. For a far greater threat invaded the adaptation.

Trust me, I wanted to love Dawn Treader. Given time, I may be able at least to like it. Yet this element I will never appreciate, as I Tweeted shortly after coming back from the film:

Whose horrible face was that I saw floating around in #DawnTreader ‘s Evil Green Mist™? Why — could it be — Pelagius?

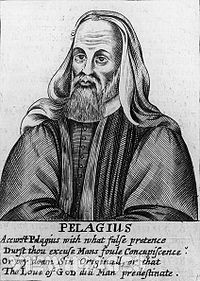

Pelagius was a heretic from the fourth and fifth centuries. But he was not the first to popularize his notions, and him dying didn’t stop them from infecting popular Christianity (thanks also to the 19th-century revivalist Charles Finney). Wikipedia gives a great summary of Pelagianism:

[O]riginal sin did not taint Human nature and that mortal will is still capable of choosing good or evil without special Divine aid. Thus, Adam’s sin was “to set a bad example” for his progeny, but his actions did not have the other consequences imputed to Original Sin. Pelagianism views the role of Jesus as “setting a good example” for the rest of humanity (thus counteracting Adam’s bad example) as well as providing an atonement for our sins.

The heretic Pelagius (ca. 354 – ca. 420/440)

Most Christians would rightly insist they don’t believe all of that. Yet might some of it sound familiar? I know that I’ve previously accepted some of those beliefs. And how often have you heard something said like, “If God commanded it, we must be able to do it ourselves”? Pelagianism.

That and similar beliefs are based on overreactions. Pelagius saw people who lived in a “cheap grace” way and wanted to fix that problem. Unfortunately he didn’t fix it according to Scripture.

Of course, Christians often accept un-Biblical notions, so it makes sense that non-Christians would even more buy into Pelagian ideas such as “look into yourself to find goodness.” Sadly that proved itself again in Dawn Treader, despite the film’s respect for Lewis in other ways.

As blogger Trevin Wax summarized:

How in the world does Lucy’s temptation for beauty become a message that tells viewers, “Just be yourself.”? Yes, the film gets it right that “evil is inside you.” Glad to see that. But the film teaches that the resolution to the evil in you comes from being true to your deeper, better self. Willpower saves.

Elsewhere, Reepicheep mentions “[earning] the right” to see Aslan’s Country. Aslan himself says “my country was made for those with noble hearts.”

Perhaps I shouldn’t have expected non-Christians to relay Dawn Treader’s real worldview more effectively. Again, even Christians fall into emphasizing self-esteem more than God-esteem, as if we love God above ourselves but also expect Him to return that same favor in our direction.

But I can still complain, and suggest re-checking our beliefs, and not just as some legalistic or academic task. Pelagianism’s lies offend the God we love, split churches and hurt people.

More specifically, Pelagianism does weaken Christians’ visionary fiction. I won’t say names here — partly because, sorry to say, the titles and authors can be forgettable! — but I’ve read a few fantasy books whose authors are trying to Imitate Lewis. But there’s a catch: their Christ-figures, a la Aslan, aren’t much like Aslan, much less so the Biblical Christ. Sure, they have all the loving-humble-helpful parts, but few to none of the sovereign-holy-kill-his-enemies parts. And these Christ-equivalents exist, not with their own missions, but mainly as sidekicks for the real hero of the story, the Self-Doubtful Often-Angsty Gifted protagonist, who is on a Quest.

Stories making God or a Christ-figure a means to fulfilling one’s Destiny, rather than centering on Himself, are little better than atheism. Sadly, the “Voyage of the Dawn Treader” film suffered from those wrong beliefs. Without knowing and loving God’s God-centeredness, so will other stories.

Much of C.S. Lewis’ genius, and Aslan’s grandeur, came from his knowing God is gracious *and* terrible. Miss that, and you de-claw the Lion.

Many other fantasies also want to imitate Lewis and convey truth about Christ. But they end up making Him a sidekick for humans’ adventures. Christ is not a sidekick. We are. He should be the center of all stories. Neglect that, and all Narnia-imitating hopefuls will ring hollow.

Sure, not every story can have an overt Jesus-figure or all the Gospel on all pages. Not even the Bible has that. Yet it’s about trajectory.

(That was from more Tweets.) Next week I may write more about fiction Pelagianism. Or about Santa Claus. It depends on reactions, which are certainly welcome.

I love this piece brother. Thank you so much for writing it. I would love to see either piece. If you do write about Santa though, be more balanced, not all of the Santa mythos is evil, or God-dishonoring. Only those who replace Jesus with him are. God bless. 🙂

Yeah, that was one of my thoughts while watching the film: “Enough of the ‘Trust yourself/look deep in yourself’ crap” — for I find no better word for such drivel. Also, speaking of the film as a film only, the Green Mist and its accompanying “theme” of temptation was overused and generally appeared to bludgeon viewers’ noggins, despite its ambiguity everywhere else.

A few scattered thoughts…

I think a lot of the mainstream “Christian” reviewers like PluggedInOnline and Crosswalk were very favorably impressed with the VDT film… a disturbing trend, to say the least. But not a surprising one. Slap a Christian label on something and everyone in the “faith community” will jump on the bandwagon. It doesn’t have drugs or sex or too much violence in it? Great, let’s endorse it wholeheartedly! But there are other elements that are more insidious and no less dangerous than the big three we usually worry about.

Unfortunately, bad theology is the norm rather than the exception in “Christian” fiction nowadays. It’s almost enough to make me give up on the genre. A recent foray into Christian fantasy revealed a pathetically weak Christ-figure who was introduced in the story by the protagonist having to rescue Him from a life-threatening situation. Throughout the story, this Christ-figure did nothing but serve the protagonist, who was never in any kind of awe of Him. Gone is the majesty, reverence, and awe we should feel, replaced instead with a contemptible familiarity.

I believe this author was attempting to depict Christ’s love and compassion through this character. And yes, God is love and Christ loves His church. But when you present a Christ-figure with only ONE of Christ’s attributes, the result is inevitably a skewed representation. And this is a serious problem… this is Christ you are claiming to depict! That in itself should make us approach the task trembling.

So say I’m a writer trying to depict a Christ-figure in my novel, and that Christ-figure is a weak one. He is just there to help and serve my protagonist, and I have come to realize that this is not an accurate depiction of Christ whatsoever. How do I fix this?

The problem lies deeper than my creative conception and writing. I need to stop writing, stop trying to inject more artificial majesty and power into my character, and examine my personal theology. We can only create what we know, and if the Christ-figure in my novel is pathetic, my conception of Christ is pathetic. There’s no way around it. And the only way to fix it is to fix my theology. Everything flows from that.

And as a side note, taking CSL’s Aslan as my model isn’t a good move either. Yes, Aslan is an absolutely brilliant Christ-figure and I can’t think of anything CSL might have done to improve the character. But Aslan is not Jesus! I need to base my Christ-figure on the real thing — Christ. And that means I should be seeking my inspiration and spending my research time in His Word.

Can other Christians’ creative portrayals of Christ be helpful? Yes. But I shouldn’t make those portrayals my model or primary source material. CSL’s creation is a good example of what to do, but it’s not what to do, if that makes sense. So many writers today are trying to imitate CSL and other greats in the Christian fiction tradition, but I have never seen it work. (An exception *might* be Alcorn’s Lord Foulgrin’s Letters, which I have not yet read. But even in that, I’m sure Alcorn tried to bring new issues to the work rather than merely copying and pasting from CSL’s more famous Screwtape.)

I propose a new way of thinking about our Christian novels: what if our Christ-figures actually become the protagonists, with the Other Characters Representing Us less of the focus? Is that too crazy of an idea? Because really, the real-life story isn’t about us anyways. It’s about Him. He is our sovereign… not our servant!

I did notice that, and unfortunately it’s not only illustrative of some Christians’ tendency to be overly optimistic about Things Advocating Moral Beliefs (as if that’s just next door to Christianity), but some Christians’ tendency to fall for overt cliches. For example, who is it, really, who’s out there encouraging people “don’t be yourself, be someone else”? Is it really so impressive to contradict that? One might as well oppose, say, earthquakes, or child abuse, or Intolerance. As Jesus said, even evil people give good gifts to their children (Matthew 7:11). But He’s not impressed.

Thanks for your extension of ways to fix the problem of seeing Jesus in a shallow way — something I didn’t go into as much, at least not yet. It’s very likely that would be more of a nonfiction column instead of, as you said, simply advice on how to make the Jesus-parallel-character more majestic and such. Trying to inject majesty or “not tame”-ness into a character would not work, if you’re not as personally familiar with those characteristics of the One upon Whom the Christlike character is based.

So, one question for discussion: how can we do that? And, if we know Christian readers or writers (or movie critics!) who are too overly impressed by beliefs or stories labeled “Christian” but that emphasize man-centeredness, how might we graciously share with them that there’s more to Jesus than the love and humility (though He has that too)?

One would have to be very careful about doing that — because a novel all about a Christ-parallel-like character could seem redundant or unnecessary.

I can understand a Christian fantasy/sci-fi/whatever having more “face time” for a human character, with whom a reader can identify. Yet what does that “face time” tell a reader? “Empathize with this character only, and see how ‘Jesus’ helps him/her find Destiny, just like He can help you find yours!” Or is it: “God is incredible, loving, majestic, holy, sovereign; see how this character who might be like you needs Him, and needs to repent of his sins and trust Him alone for love and salvation.”

The latter is both unique in that it’s not so prevalent in current Christian fiction, and much closer to the Biblical truth. I’d love to find and read more of those kinds of books.

Great stuff you talk about, although I cringed a bit at your attack on writers (like myself) who write fantasy books where many of the qualities and character of Christ is embodied in a character or animal (like Aslan) to accompany a hero on his journey, or whatever. In my case, I am not trying to make the wolf in The Wolf of Tebron BE Christ. Like lewis said, he was not trying to teach Christianity, only help others experience it. For me, portraying a wolf with qualities of loyalty, faithfulness, encouragement, fierce protectiveness, kindness were was I could explore some of the facets of God’s nature. Books like this are not meant to belittle or cheapen God, his power, or sovereignty but I believe they are very important in helping a reader be drawn to God. Aslan is a bit of a sidekick in Narnia. He only shows up from time to time and the humans take center stage through the stories, so I could make the same complaint for Narnia. But unless an author is directly saying or implying God IS a lion or he is ONLY like this, exclusive of any other qualities, is taking it a little extreme IMHO. With fantasy, we should be able to indulge in these forays of imagination without getting too caught up in expecting a fantasy character to be exactly like God. Only God can be God.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by E. Stephen Burnett, Speculative Faith. Speculative Faith said: A unique kind of monster infests the #DawnTreader film, and much more subtle than Evil Green Mist. http://bit.ly/fomgkb […]

Good news and bad news, Susanne! Bad news first: I haven’t yet read The Wolf of Tebron, though I’m working on it. Good news: I haven’t yet read The Wolf of Tebron, so my thoughts (not personal attacks on any author or story) weren’t based on that.

I’m a bit uncertain what you meant by “teaching” versus “experiencing” Christianity. Help me out on that? 😀 Perhaps it’s from a Lewis quote I’ve missed. Yet my cursory response (which could be based on a misreading of what you meant) is that personal experience can “confirm” either truth or lies; therefore, the best kind of experience is based on God’s truth, which we learn — the “creeds” — and apply — the “deeds.”

Is Aslan a “sidekick”? I might disagree with your view that he is. Yes, he only shows up in Narnia occasionally, so by number of appearances only, one could say he’s a minor character. But his real nature and role are revealed not by the quantity of his appearances, but the quality: he is clearly in charge, sovereign yet loving, not tame, but good. And his goals for bringing the children to Narnia, anointing its kings, overseeing its history, being directly present for pivotal moments, etc., makes it clear that the human characters are blessed to be part of his plans and to know him, and don’t mainly have him as accessory to their own Destinies or Quests to Fulfill (though that element is present, it’s secondary).

Methinks one need not have a character who “is” Jesus; I hope that is not what I’ve argued. Rather I’ve suggested Christians seek (and write about!) greater depth to their portrayal of Christ and His nature in their fiction. Of course it may take several stories to do that, comprising an author’s fuller body of work — like Scripture itself. What I mean is that sure, the Bible doesn’t info-dump about what God is like, what truth is and what Christ has done, all on one page or one book. Yet it’s clear by the Bible’s main story what truth is, and said in so many different ways, with different nuances: song, narrative, theological argument, personal letters, high fantasy (Revelation), etc.

I’d love to hear more about fiction Pelagianism! This is great food for thought.

Hey Mr. Burnett,

I thoroughly enjoyed your well thought out and well explained post. I myself have not seen the movie. However, I echo your concern having heard it. Thanks for the informative post.

I would hasten to agree however that in the Narnia book serious, which I’ve read maaannnnyy times, I see Aslan not as a sidekick but as indeed the one in control. Always at the edge of the picture, a little in the fuzz, but not afraid to show himself.

Anywho..thanks for the post. If I can manage to remember this site I will try to make it regular visiting. >_<

I really don’t know the answer to this question. My instant response is to get into combat gear and let them have it. There is a place for vigorous discussion, but there’s also a place for more persuasive methods. But really, I’m not going to change anyone’s mind no matter how I present my views. I guess all we can do is continue speaking the truth in love. Maybe approach these undiscerning Christians with questions rather than statements about what they’ve gotten wrong? I don’t know, just thinking aloud here. Great question, Stephen.

Very true. And after I posted that I thought of a cycle that attempted just that, Calvin Miller’s The Song, The Singer, and The Finale. To be brief, I was not impressed. Miller apparently felt the need to introduce some kind of angst to his Christ-figure, so he made Him unaware of who He was. The whole thing is about the Singer realizing He is the Son of God and what His destiny is. Aaaarrghgh.

This surprises me quite a bit. Aslan a sidekick??? No way. I doubt you will find many Christians who share your view; that sounds like something I’d read in a review from a non-Christian over at LibraryThing or something. Very man-centered.

Aslan is the only character who appears in all seven of the Chronicles, the consistent thread holding it all together, the One all the buildup is about. Every time He shows up, it’s a BIG deal. He’s never just there to pander to the humans; He has a majesty and glory all His own. The human characters fear as well as love Him.

Creating a character with intentional parallels to Christ is a heavy responsibility. I am not sure how I would do it myself — but I do know many things that I would avoid doing.

And Aslan’s presence is always felt throughout the series, whether he’s presented overtly or not. He’s definitely not the side-kick. The Chronicles of Narnia are effectively all about Aslan.

Hello Stephen Burnett. I put a couple of (appreciative) comments on the “book CSL didn’t write” thread over here: don’t think you’ve seen them yet! Hey is everybody asleep in the new year? I haven’t actually seen the film and it doesn’t sound like it’s worth a special trip. My Cornish town is getting a (new) cinema for the first time since 1994; but it is still being finished and won’t be open until Easter, with luck. So I suppose it’s the DVD for me!

I’m a big fan of CS Lewis; though have realised for a while that I’m not temperamentally suited to be a Christian! My beef is with the way H-wood changes things to give them a bland or generic message. Or it has a tendency to over-complicate plots and/or mix in a slew of stuff from practically random sources. I believe this is called postmodernism (though it is not always an evil practice!) Postmodernism on the whole loves pastiche, as the architects call it!

Quentin Tarantino epitomises that sort of thing in his movies! I also think they are trying to compete

with modern US TV serials; which can be quite complex; also they probably get this “anything-goes-and-will-do” approach from modern US comics; which tend to feature endless crossovers, and nowadays are usually like the most abysmal soap opera you have ever seen, mixed with shlocky sci fi/horror, and contain nothing that dares to be inspiring or uplifting any more; let alone humorous in the sense of “funny papers”! (This is not just from the Christian point of view: the strange thing I think is that DC and Marvel don’t even tend to cater for “new age religion”; or so much as multi-culturalism – or anything! That isn’t totally negative/nihilistic! A far cry from American culture 60 years ago! Anyway, that was FYI, in case you were unaware of it! I encourage you to research/cover the particular area.)

Hollywood though, tends to be blander and not so negative; this must be bcos of the need to cater to a wide audience. I would say that on the whole it doesn’t like ideas or ideology at all; so nowadays tends to go

for the “things will be OK; look within yourself” Disney-type message in all but horror films! But the thing is a lot of modern films are bland – and don’t like ideas. You will find that goes even truer for leftist ideas as it does for Christianity! Take that recent movie based on an Upton Sinclair novel, There Will Be Blood. Did you learn much about early 20th c. socialism or labour from that?! Well then: Sinclair was to American socialism what Lewis was to British Christianity.

But returning to VDT – I’m glad if they got the characters at least of Reepicheep and Eustace right! Tell me please – was his transformation into/out of the dragon harrowing, and affecting enough?? Would that part have scared most kids – and inspired Aristotle’s famous pity and terror?! I bleddy hope so! (And did Aslan pull all his dragon skin off?)

But as for all that green mist/seven swords stuff – that is just generic s&s: what was it doing in there? The novel is plenty complex enough to fill a 2-hour or more movie.

Stephen, I’ve read several of your entries on the subject. Having not seen Voyage of the Dawn Treader yet, I’m going to let those comments pass for now. But I can’t quite seem to get a good fix on some of your thoughts regarding theology in fantasy. (And forgive me, because I’m going to be a bit all over the blog here.) I guess I’m not sure what to make of the four categories you listed in one entry (and forgive me for not being able to link it right now – I’m not signed in). My confusion, I suppose, arises perhaps when it comes to instances such as the Harry Potter movies, which, while good and evil are clearly defined, don’t really have a god – and most definitely not God as we know him – versus the Narnia movies. I suppose perhaps I’m surprised that VTD receives so much hostility in comparison.

I’m not trying to be contentious; I’m just finding it hard to pin some of this down. Course, I also still have trouble reading off a screen. 0=) It’s also hard to discuss a movie I haven’t seen.

Um, I’ll say more about the four categories thing when I’ve got more articulated thoughts. And those comments should likely go under that entry anyway. Again, please forgive me for being all over the map.

Amy – I believe this author was attempting to depict Christ’s love and compassion through this character. And yes, God is love and Christ loves His church. But when you present a Christ-figure with only ONE of Christ’s attributes, the result is inevitably a skewed representation. And this is a serious problem… this is Christ you are claiming to depict! That in itself should make us approach the task trembling.

I could hug you for that. Been screaming that one for years.

I propose a new way of thinking about our Christian novels: what if our Christ-figures actually become the protagonists, with the Other Characters Representing Us less of the focus? Is that too crazy of an idea? Because really, the real-life story isn’t about us anyways. It’s about Him. He is our sovereign… not our servant!

It would either be a very short book, or a very long book where for decades and centuries very little “on screen” appeared to happen, and then suddenly the plan goes into execution phase.

Personally, I’m absolutely terrified of the idea of trying to accurately write Jesus.

Course, maybe I misunderstood. Could you expand?

Stephen – And, if we know Christian readers or writers (or movie critics!) who are too overly impressed by beliefs or stories labeled “Christian” but that emphasize man-centeredness, how might we graciously share with them that there’s more to Jesus than the love and humility (though He has that too)?

I think it falls under the “work out your own salvation with fear and trembling” clause, personally. But I always explain it something like this: “Name me a king who is just but not merciful. Name me a king who is merciful but not just. One does not exist without the other, because when a king simply pardons wicked men, he is unjust; and when he refuses to extend the hand of grace, he becomes a merciless tyrant.”

I think the whole “God is only Love” thing stems from some kind of backlash against legalistic spiritual oppression (real or perceived). There’s as many flaws with overemphasizing God’s sense of justice as his sense of grace: the truth is he is both, and they are not polar opposites. They are wedded together.

This surprises me quite a bit. Aslan a sidekick??? No way. I doubt you will find many Christians who share your view; that sounds like something I’d read in a review from a non-Christian over at LibraryThing or something. Very man-centered.

Sidekick is most likely the wrong term, but he’s definitely more that “uber powerful/wise man” guy who’s got the plan and the means of carrying it out but isn’t himself the main character. Nothing happens without him, but the story arc lies with another.

Methinks one need not have a character who “is” Jesus; I hope that is not what I’ve argued. Rather I’ve suggested Christians seek (and write about!) greater depth to their portrayal of Christ and His nature in their fiction. Of course it may take several stories to do that, comprising an author’s fuller body of work — like Scripture itself. What I mean is that sure, the Bible doesn’t info-dump about what God is like, what truth is and what Christ has done, all on one page or one book. Yet it’s clear by the Bible’s main story what truth is, and said in so many different ways, with different nuances: song, narrative, theological argument, personal letters, high fantasy (Revelation), etc.

This goes back to my first comment. Just so you know I’m not totally nuts. Or at least, not admitting to it. 0=)

I don’t think any of us are “temperamentally suited” to be Christians! In fact, the Bible says that by nature we are all suited to be the opposite… and are. Anyways! 🙂

Say you are in love with someone. Would you prefer a movie that simply doesn’t mention that person at all, or a movie that skews that person’s character and presents him as someone he most certainly is not? The analogy is flawed, of course, but I think the point is valid. HP doesn’t claim to represent the character and nature of a deity. Narnia does.

This is the argument I don’t understand. Many people seem to think that we should just be happy to get any kind of nod from Hollywood. But that’s not good enough; just because someone put a Christian label on a movie doesn’t mean it’s Christian. I’m not going to be happy when someone swears using Jesus’ name, just because my Lord was mentioned!

Going back to HP for a second, good and evil may be clearly defined but the definition rests on our outside-the-book moral foundation, and that is derived from God. Dostoevsky said it: without God, everything is permissible. There is no reason that murder is morally wrong without a God who says so. As humans, we’re all on the same level — something I think is wrong you might think is right, and who’s to say which opinion is the moral one? We need a higher authority than ourselves from which to derive morality or everything falls to pieces. Rowling cannot define good and evil without this moral framework already in place in her readers’ minds. This isn’t an argument saying God actually *is* in the HP books, just a comment on how good and evil can even be defined.

Well, the Book has already been written, of course! Maybe attempting to create a Christ-figure at the center of a fantasy novel is too ambitious (and as I noted, didn’t work too well in Calvin Miller’s books). I am just trying to think out loud and find alternatives to the Christ-figure who is just along to help the human hero. Bad theology can be far more dangerous than no theology at all!

[…] Stephen Burnett wrote a post on SpecFaith about how we depict God in our fantasy. Entitled “Fighting man-centered monsters in fiction,” it used the recent Voyage of the Dawn Treader film as a jumping-off point to address […]

Finally I have some time to respond to your comments, Liz K.

First I must echo Amy Timco up there about your comment that you’re “not temperamentally suited to be a Christian!”. I wonder what Lewis would say in reply to that thought — surely he wasn’t either, having been raised in academia, pagan myths and default agnosticism/atheism! Moreover, apart from what he believed, I find in the Bible that no person has the “temperament” to be a Christian. We’re all rot-gut sinners, our hearts full of crap and rebellion against our Creator. Only because of what He has done, especially taking His own watch upon Himself in His people’s place — can we have our hearts changed, to delight in Him and also everything He gives us — including imagination, beauty, and fantastic stories that echo His truths.

Though it’s impossible to know the Dawn Treader screenwriters’ motives, I can make educated guesses based on (as I’ve previously written) the default view of professing Christians about who, really, God is working for. Whereas the Bible clearly shows He does all things for Himself and His own glory (references available upon request), some act — or claim outright — as if He is falling all over Himself to “love” people as His highest goal, as if we were little gods and He needs us. Ugh.

Knowing that audience, and having that hidden belief deep in their hearts by default — it’s the common element to all religions, except Biblical Christianity! — why wouldn’t the screenwriters buy into that bland, generic doctrine and promote it in the film? I suppose I should not have been surprised. But Lewis, despite his other faults, seems to have understood the God-centeredness of God, and thus made the land of Narnia very Aslan-centered, even when Aslan was hidden. He had his own agenda, and the children, kings, creatures and everyone else, were blessed to follow in it, and to know him personally.

If the writers had respected that, they could have made a much stronger film, even with some story changes. After all, Peter Jackson and his co-writers were not Christians and never professed respect for the Bible or Christian ideas, yet many of Tolkien’s powerful themes got through to the film versions beautifully because Jackson and Co. respected Tolkien. I just don’t see as much of that in the Voyage of the Dawn Treader film, in both its “theology” and its story.

Briefly on “postmodernism”: it’s used to describe a lot of things, including mere moral relativism, but in this case I think you’re right that it figured into the film adaptation process. One tenet of postmodernism is the inclination to think that new = better and new > old. And I do not hold to that.

Sadly, it seems the screenwriters did in too many ways.

Lewis’ values / books’ values = courage, chivalry, not seeking adventure for the greater end of “things useful” but for honor’s sake and seeking Aslan’s own Country above all else.

Screenwriters’ views / film’s values = Aslan as means to self-help, seeking useful items (find the Seven Swords™!) with finding Aslan’s Country merely a surprise bonus feature, etc.

Bleddy no. There was a transformation, but (spoiler warning) it ripped off Beauty and the Beast, and wasn’t nearly as powerful as even that transformation sequence and effect. And, of course, the film’s version was not as powerful as the book’s version, which made it clear how futile Eustace’s efforts to save himself were, and the pain and then glory of the salvation only Aslan could give.

Some say “well, that would have been too violent for a PG film.” I suggest intensity does not have to be violent. Regardless, the film rushed through that scene as quickly as possible, simply as a means to a more “useful” end, then got back to the real action and what its writers really wanted to talk about: Sea Serpent Battle (!!!!!). The heart wasn’t there, despite some dialogue later when Eustace recalled the un-dragoning.

And one could have strengthened its existing themes — honor, adventure, seeking Aslan’s Country as a goal worthy of sailing into unknown waters — without swapping those out for generic defeat-the-enemy fantasy tropes. My guess is that Americans have lost not only a healthful respect for Things Outside Themselves, but the pioneer spirit altogether. This affects even the space program: no one wants to fund a Mars mission, because what use would it be to me personally? No room given for valuing the Other for its own value, much less for what it shows us about God’s creative majesty. That’s why Dawn Treader had to get turned into a bland, generic Quest Narrative, with little to no place given for the voyage-of-honor-and-discovery themes.

Hmm. Well that was some reply, that made some interesting additional points! So you feel that no-one, not even Lewis, was suited to be a Christian? Hmm well.. you know a lot of what you are, including religion, is sociologically determined by position in time and space? And in a free society, much choice has to do with that mysterious element called personality? As for Lewis being brought up a pagan, an academic or an atheist – er no, if that’s what you were saying! He was brought up, albeit in a house “filled with books”, in a middle-class Protestant household; he was the second son of a solicitor on the outskirts of Belfast. (I’ve read Surprised By Joy, many times.) He however did not enjoy worship as a child (as his autobio and an allegory, The Pilgrim’s Regress, make clear – that as a child, he just found Christianity frightening and of very little comfort to a small boy who had lost his mother.) It was the pagan stories that fired his imagination! After some unpleasant “public school” experiences he lost

Of course! And we believe there is Someone who is sovereign over sociological determination, time, space, and everything else.

It’s no accident 🙂

(Note the Scripture reference is from Acts 17, verses 26 and 27. For some reason the blockquote didn’t accept my cite code.)

Alas, Amy, I also tried that recently, and it seems it only works if the citation is a hyperlink.

[…] just for a glimpse of Aslan’s Country—a world that transcends all our hopes. In place we heard “brave” themes about believing in one’s self and following dreams, as opposed to all those movies that urge us to ignore ourselves and declare the heck with our […]