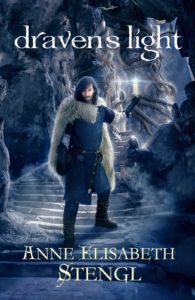

Fiction Friday – Draven’s Light By Anne Elisabeth Stengl

Draven’s Light (Rooglewood Press)

From The Tales Of Goldstone Wood

By Anne Elisabeth Stengl

Introduction

In the Darkness of the Pit the Light Shines Brightest

Drums summon the chieftain’s powerful son to slay a man in cold blood and thereby earn his place among the warriors. But instead of glory, he earns the name Draven, “Coward.” When the men of his tribe march off to war, Draven remains behind with the women and his shame. Only fearless but crippled Ita values her brother’s honor.

The warriors return from battle victorious yet trailing a curse in their wake. One by one the strong and the weak of the tribe fall prey to an illness of supernatural power. The secret source of this evil can be found and destroyed by only the bravest heart.

But when the curse attacks the one Draven loves most, can this coward find the courage he needs to face the darkness?

Excerpt

Each step dragging more than the last, the girl climbed the winding track up the hill. She progressed so slowly, with such hesitation, that one might have thought she bore a terrible weight. But no; her arms clutched the water skin to her thin breast without apparent strain. She had carried far heavier burdens often enough in her short life. Nevertheless, her pace dragged, and her gaze, darting up the path and down again to stare at her feet, was filled with apprehension.

“I need you to make the run for me today,” her mother had told her but a short while ago. “I have no time, and it is the least we owe them. Hurry, child.”

“Cannot Grandmother go with me?” the girl had protested, her eyes rounding even as her mother placed the waterskin in her hands. The outer hide was slippery, and the gir was obliged to hold it close so as not to drop it.

“Certainly not!” her mother had replied. “You hurry along now, and don’t be bothering your grandmother. She needs her rest and can’t spend her days holding your hand anymore.”

But the girl hadn’t moved. She had stood quite still, the waterskin dampening the front of her rough=fibered gown, staring up at her mother. Then, very softly, she said, “I’m afraid.”

But her mother had no patience. “Afraid of what?” she cried and, without waiting for an answer, turned her daughter around and gave her a firm push toward the hill-winding track. “Don’t be a coward. Go on! It’s wrong to keep those poor men waiting all day. I can’t be expected to run every errand, and you are quite a big girl now.”

She didn’t feel quite a big girl. She felt small. She always felt small when she walked this track, but never so small as she did now, climbing it alone for the first time. Always before she had gone in company with someone: her father, sometimes her busy mother, even one of her aunts or older cousins. Always before she had held onto someone’s hand and gathered courage from a stronger grasp.

But not today. Today she must face the enormity of the Great House on her own. The Great House . . . and the Brothers who built it.

As long as the girl could remember, the Brothers had worked on the top of the hill, going about their endless labor. As long as she could remember, she had watched from Kallias Village down below as, day by day, month by month, year by year, the great walls had risen up from the tree line to tower on that promontory above the river. In winter the labor ceased for a time, and the Brothers went away to far-off quarries (or so her father told her), there to mine and shape enormous blocks of stone.

But as soon as the binding of winter gave way to the freedom of spring, the Brothers would return, accompanied by strange, fierce folk and stranger, fiercer animals, hauling the new stone up the track—which was quite wide by now after many years of this cyclical process—up to the very top of the hill. The strange folk and the fierce animals always left soon after, never speaking to the men or women of the village.

But the Brothers remained. And throughout the rest of the year the ringing song of hammers upon stone echoed down from the promontory, as much a part of each day’s music as birdsong or the voice of the river itself.

The girl heard the hammer song now—Clang! Clang! Clang! Only one hammer singing a lonely melody, she thought. Slow and rhythmic, without haste but with great patience. She matched her stride to that beat.

Clang! Clang! Clang!

Step. Step. Step.

Though her pace was reluctant, her heart beat like mad in her breast. She could feel it thudding against the waterskin. Would the Brothers speak to her? They never had before, though the Kind One had smiled at her upon occasion. His was a nice smile . . . but still! She dreaded the very thought of his speaking and, worse, expecting her to answer.

The walk up the hill was a long one, but the late-spring day was fair, and the girl’s going, slow. She should not have felt so winded. But as the trees gave way at last to the large clear space at the crown of the hill and she looked out upon the rising stone walls of the Great House, she gasped and could hardly catch her breath.

To compare the Great House to even the largest structures of Kallias Village would be like comparing the wingspan of the northern eagles to that of the little chaffinches living down in the brier. The difference was so vast that no comparison could be justly made! The Great House, even unfinished as it was, could have held all of Kallias in its main hall and many of the fields surrounding in its courtyard. The doors themselves, newly carved and hung by the hand of the Kind One, were each as large as the entire floor space of her father’s house. The stones comprising the walls—so carefully cut in those fabled, far-off quarries and shaped upon arrival to fit seamlessly one against another—were shot with blue and gold, unlike any mined in any quarry within a hundred miles, perhaps within a thousand. Indeed, these stones were so otherworldly in their beauty, they did not seem as though they could come from this world at all. The gold in them caught the light of the sun and held it, warm and glowing and alive.

But while this was enough to overwhelm the girl, it was not enough to make her afraid. No, she trembled because, through the open door, she could see inside the hall. And it was dark. Dark like the fall of night. Dark like the mouth of a yawning mine. Dark like the beginning and the end of the world. Though the walls were lined with tall windows and the roof above was as yet incomplete, its rafters etched against the sky like the ribcage of some giant beast, no light seemed able to penetrate down into the shadows cast within.

So the girl stood on the edge of the tree line, staring up at the Great House and unable to make her feet move. She saw, high above on a wooden scaffolding, a tiny figure moving. The figure was tiny only from distance, and even at that distance she knew the form at once fro one of the

Brothers. The Strong One, as she always thought of him.

The singing hammer stopped. The figure of the Strogn One stood and stretched. She knew that he had seen her, and she knew that she must proceed. They were expecting her, after all.