Conversions And The Goal Of Christian Speculative Fiction

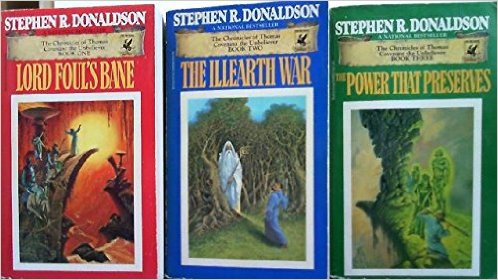

Even though he isn’t a Christian, one of the writers who influenced me was Stephen Donaldson, author of the Thomas Covenant chronicles. Years ago I read an article of his entitled “Epic Fantasy In The Modern World” that helped me understand the point and purpose of fantasy. He said

fantasy is a form of fiction in which the internal crises or conflicts or processes of the characters are dramatized as if they were external individuals or events. Crudely stated, this means that in fantasy the characters meet themselves – or parts of themselves, their own needs/problems/exigencies – as actors on the stage of the story, and so the internal struggle to deal with those needs/problems/exigencies is played out as an external struggle in the action of the story.

A somewhat oversimplified way to make the same point is by comparing fantasy to realistic, mainstream fiction. In realistic fiction, the characters are expressions of their world, whereas in fantasy the world is an expressions of the characters. Even if you argue that realistic fiction is about the characters, and that the world they live in is just one tool to express them, it remains true that the details which make up their world come from a recognized body of reality—tables, chairs, jobs, stresses which we all acknowledge as being external and real, forceful on their own terms. In fantasy, however, the ultimate justification for all the external details arises from the characters themselves. The characters confer reality on their surroundings.

I suspect science fiction and horror (and all the permutations of these genres) is closer to fantasy than to “realistic fiction,” though I could be wrong about that. But for the sake of this post, I’m more interested in the idea that the speculative genre is part of delving into the character—understanding his fears and weaknesses and hopes and strengths and goals. The imaginative physical world takes on more significance because it reveals not just the world, but the character.

The question I have is this: do Christians write the story of one character, or the story of Humankind?

We know all have sinned, all are sinners. We know all need a Savior. We know Christ loves the world and that He gave His life for sinners. Because those particulars are shared experiences, I wonder if Christians who write Christian stories—speculative or realistic—might write a story that seems generic.

Not all Christians sin in the same way. Not all people sin in the same way. Not all people who hear the gospel believe they need a Savior and surrender their lives to the One who sacrificed for them. Not all people have the same questions about spiritual issues. Some struggle with morality, some with whether or not God exists, or if He does, why He allows pain and suffering.

Christians who want their readers to encounter spiritual truth in their fiction may assume that the more general they make their story, the more people they’ll include, but in reality, the opposite is true. When we write about the human experience, the particulars a person goes through touch our hearts, not the generalities.

I love hearing Christian testimonies. My church used to have each person tell about how they came to faith in Jesus Christ as part of the baptismal service. It never got old. At times I would tear up. Why? Certainly not because they said something general. No. The stories that stuck and were memorable or touching were those that were unique to them. Like the couple who would pass our church week after week on their way to play golf on Sunday morning. They saw lines of cars and people pouring into this church building, and they couldn’t help but be curious. Why would people choose to go to church instead of sleep in or play golf? So they visited our church and in the course of time, they came to know and accept Jesus as their Savior.

“The course of time” is the generic part of the story. Their unique way of coming to our church for the first time, is the particular part that made it memorable.

Does that mean others will likely not be able to relate because their circumstances are too different? Not at all. The miraculous and the amazing is a reflection on God and something all of us can understand and appreciate. When I hear of someone coming to Christ because of the witness of little old Dutch lady in a Nazi concentration camp, or of an orphan in India becoming a believer because of a stubborn, tough minded maiden lady, or of an entire people group in the Amazon jungle turning to Christ because of the testimony of two widows of the men they murdered, I don’t think the stories have nothing to do with me or nothing to say to me.

Does that mean others will likely not be able to relate because their circumstances are too different? Not at all. The miraculous and the amazing is a reflection on God and something all of us can understand and appreciate. When I hear of someone coming to Christ because of the witness of little old Dutch lady in a Nazi concentration camp, or of an orphan in India becoming a believer because of a stubborn, tough minded maiden lady, or of an entire people group in the Amazon jungle turning to Christ because of the testimony of two widows of the men they murdered, I don’t think the stories have nothing to do with me or nothing to say to me.

Instead, I see the courage, kindness, selflessness, trust, and love of those who shared the good news, and I see the power of God to bring about a remarkable change in the lives of those who recognized their need for a Savior. Those stories challenge me and give me hope.

Generic stories, not so much.

All this to say, I don’t believe conversion stories are the problem in Christian fiction. Conversion has its place and can be powerful. But there’s more to the Christian life than starting it. And not everyone starts a life with Jesus Christ in the same way.

Christian speculative fiction, then, should reflect the uniqueness of the character, what her needs and struggles are. The story must first happen to and for the character before it can have any impact on the reader.

Yep. I suppose that has been my problem with Christian media. It’s all about the conversion aspect, rather than the everyday life of someone who is already a Christian. I have found very few stories like that, with the exception of some late 80’s early 90’s Christian YA mystery series, and Adventures in Odyssey.