The Christmas Story: The First Epic Tale

A bloodthirsty tyrant.

A bloodthirsty tyrant.

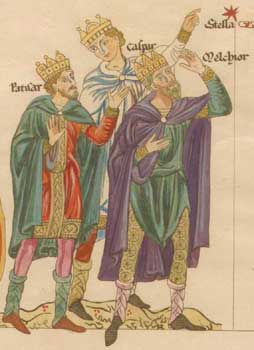

A group of “mages” from the East.

Otherworldly messengers.

A child of humble birth whose deeds would one day save the earth.

Sounds like the basic premise for three-quarters of the fantasy novels ever written. And yet, it’s anything but a fantasy.

I’m talking, of course, about the Christmas story. The first epic tale, the truth, power, and beauty of which any great tale reflects to some degree. The miraculous story of the incarnation of Christ, come from the unimaginable majesty of heaven into the sin-torn world to rescue us from the grip of the enemy.

Reflections of Truth

Decked out with all the trimmings of an epic tale, the Gospel tale—of which the Christmas story stands as the centerpiece—is the one “myth” that actually came true. In it, we glimpse familiar elements common to many imaginative stories. As Tolkien explained in his essay “On Fairy Stories”:

Decked out with all the trimmings of an epic tale, the Gospel tale—of which the Christmas story stands as the centerpiece—is the one “myth” that actually came true. In it, we glimpse familiar elements common to many imaginative stories. As Tolkien explained in his essay “On Fairy Stories”:

The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: “mythical” in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history.

Perhaps that’s why fantasy and science fiction, which often do the best job of portraying the reality of the Christmas story, are so powerful.

Many stories, whether written from secular or Christian worldviews, point us back to the story of Christ, implicitly or explicitly, by design or by accident. As if the truth of that account from two thousand years ago is indelibly branded into our beings.

A powerful tale sticks with us long after we read the final page. And, as Lord of the Rings has shown, it lays the foundation for myriad stereotypes whose essence points back to the original.

How much more powerful can a story get than one that tells of the Son of God descending to the lowly station of man, to redeem those who deserve fiery judgment? Not only because it shines a beacon of hope into our broken lives, but because it happened. The story is as real as the screen you’re reading this on right now.

It should be no surprise then, that the archetypes we so often encounter in speculative fiction reflect the most epic story in history—whether intentionally or not.

Beneath the Surface

One of the things I appreciate about stories, particularly fantasy, is the echoes of truth sounding across their pages. At its core, fantasy deals with the battle of good vs. evil, a battle starkly manifested in the Christmas story.

No sooner was Christ born than Satan began scheming how to defeat him. (And like any respectable villain, he naively grasped after the hope that he had a chance of winning.)

The thing is, not only books by Christians capture this sense of how things are. Stories told from a secular viewpoint can contain elements that drop anchor in the harbor of truth. Parts of Wheel of Time, for example, were certainly inspired by biblical elements:

- The final battle of Tarmon Gai’don

- Masema the Prophet, who spreads word of the coming of the Dragon Reborn

In the middle between obvious and obscure fall books like Lord of the Rings. Tolkien didn’t pen his masterpiece with the goal of showing Christianity, yet

By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50294355

because his worldview seeped into his writing, glimpses abound:

- Frodo bearing the heavy burden of the Ring

- Sam’s sacrificial love and loyalty

- Gandalf’s “resurrection”

Narnia, too, shows us pictures of the bigger reality. To the unbeliever, it’s nothing more than a good story. Christians, however, look beneath the surface, see the deeper meaning, and appreciate how the truth seamlessly blends into the story:

- Aslan’s sacrifice

- The redemption of Edmund and Eustace

- Aslan appearing as a lamb in Voyage of the Dawn Treader

The Power of Stories

I’m sure we’ve all read a story at some point that dug into our hearts and left us numb with amazement. What power do they possess that causes us to become emotionally attached to people and events created in some tranquil study office or noisy Starbucks?

Their power lies chiefly in the fact that they point back to the first epic tale. The true myth. The story that matters above all else—of a babe born in Bethlehem.

Because of that first epic tale, we can appreciate the many stories around us that offer fragmented glimpses of the light, hope, and joy we celebrate during this season.

To you, what epic tale best represents the truths found in the ultimate Epic Tale?

I realize you’re trying to make a different point, but I feel like I have to revoke your literary nerd card because you’re glossing over Gilgamesh, the Iliad/Odyssey, and not to mention the entire Old Testament.

Yeah, well, maybe he’s a computer nerd instead!

I was just going to click away when I saw WoT mentioned! WoT is certainly an epic and reflective of the Gospel in that way, but it’s also long and ecclectic. I used to think long and hard about just how much Rand represented Christ, and whether his nature in the WoT books meant that Robert Jordan was some kind of super-liberal mainliney cultural Protestant who didn’t really believe in the divinity of Jesus. (The Internet found out he was Episcopalian when he died….) But obviously it wouldn’t really be fair to interpret the character as a reflection of the author’s belief that closely. We might have *slightly* more basis to claim Tolkien’s work as intrinsically Christian only because of that quote where Tolkien said so.

I don’t think any story can top The Lion, The Witch, And The Wardrobe as far as representing the truths of The Epic Tale. Few others, even by Christians, portray a hero close to Aslan’s stature and power and love. He is such a good reflection of Jesus Christ. Where’s the next story that shows him so clearly?

Becky