The Nephilim walked into history in Genesis 6:4, which runs, “The Nephilim were on the earth in those days—and  also afterward—when the sons of God went to the daughters of men and had children by them. They were the heroes of old, men of renown.” The Nephilim are mentioned once more, as the terrifying inhabitants of Canaan (in reality, the ancestors of the prodigiously-sized Anakites; whether they have any connection with such groups as the Rephaites is more than I can say).

also afterward—when the sons of God went to the daughters of men and had children by them. They were the heroes of old, men of renown.” The Nephilim are mentioned once more, as the terrifying inhabitants of Canaan (in reality, the ancestors of the prodigiously-sized Anakites; whether they have any connection with such groups as the Rephaites is more than I can say).

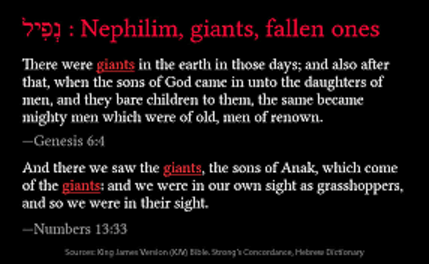

The actual importance of the Nephilim, in theology, religion, and the arc of the Bible’s narrative, is slight; their fascination is large. Their close connection to the much-disputed “sons of God” entrenches them in controversy; their association with the outsized denizens of Canaan increases the intrigue. Their name means “fallen ones,” and Nephilim is frequently translated giants, including in such venerable translations as the King James Version, the Geneva Bible, and the Wycliffe Bible. (The Geneva Bible also provides the alternate word tyrants.) Giants, fallen ones, heroes of old, men of renown – wouldn’t you love to know more about them?

One ancient, and still popular, interpretation of the Nephilim – it appears in the Book of Enoch, written before the birth of Christ – holds that they were the children of fallen angels and human women. For obvious reasons, this interpretation is the one that prevails in Christian speculative fiction. It’s not that the writers necessarily believe it, any more than sci-fi writers necessarily believe that it’s possible to go back in time or to travel faster than the speed of light; it’s just that it’s that sort of idea. The idea is acutely uncomfortable. But ideas often are in a genre that takes, for its parents, people like Edgar Allan Poe and the Brothers Grimm.

What sets the Nephilim apart from other ideas is that they are derived from the Bible. Nobody really cares whether it’s possible to go back in time when reading (or writing) time-travel stories. Nobody ever liked Star Wars less because some scientist debunked lightsabers on the grounds that that’s not how lasers work. We’re all happy to set aside debates and, for the sake of our chosen stories, presume what we suspect to be false. But should we have a different standard when the debates are centered around Scripture?

This question goes beyond the Nephilim and, if you care to follow it, wanders into all sorts of nuance. Is it all right to write a novel where the rumor is true and the Apostle John never dies? (This, too, happens in Christian speculative fiction.) Can we say that Daniel founded a school of astrology that eventually trained the Magi, though we know in our hearts that never happened? Can we have time-travelers at the Crucifixion? Can we have the Nephilim after all? Are the answers to all these questions conditional on the details, on what we do with the premise more than what the premise is? Is it simply a matter of staying in the gray and not infringing on the black and white? (For example: We can say the Nephilim were giants or tyrants or angel-human hybrids because that argument has been going on for centuries, but we can’t say they caused the Flood because they didn’t, and if you don’t believe me, read Genesis 6 past verse 4.)

What do you think? What sort of lines have you drawn, in your reading or writing?

Yeah, I think we can say speculative things about the Bible–but there’s always the fear (for me anyway) that someone would take something you said for story purposes seriously and establish a new doctrine based on a speculative idea…

Part of it depends on exactly what we write, I think. Pretty much none of my stories take place on earth. In fact, earth doesn’t even exist in much of my story universes, and I think authors in my situation have more leeway with what they put in their Christian fiction stories. Especially since, in many cases, different story universes have different circumstances. In one of my universes, for instance, time travel is possible for a certain race, but in my other universes, time travel is something only God has control over. Having things be different in each story universe might help, because people who read all these different series will have evidence that certain worldbuilding elements are there for the sake of the story, rather than something that Christians are supposed to believe.

I do worry about some things, though. The way I depict demons and angels in my stories tends to be fairly consistent across my story universes, with some minor changes. But, that leads to the idea of blogging about one’s stories a lot. Writing posts about where one actually stands on issues like that can be helpful, though those posts don’t always have to be blunt and direct in order to communicate our stance on such matters.

Frank Peretti’s “This Present Darkness” is the perfect example of this. How it can be used well, AND how readers can make it go awry. (Meaning readers have based their theology of spiritual warfare off Peretti’s book rather than Scripture)