Against the Tragic Villain Backstory

Ming the Merciless. Image Credit: Villains Wiki.

Once upon a time in speculative fiction (say in the heyday of Flash Gordon, first published in 1934), most storytellers wrote as if good was good and evil was evil. Writers might use speculative fiction to explore the nature of good and evil by attempting to distill the purest imaginable form of each and set them at war with one another (which is arguably one of the great achievements of The Lord of the Rings) but nobody had to explain why the villain was villainous–Sauron and Ming the Merciless were just bad, period. That “once upon a time” has mostly disappeared–villainous characters today are often given sympathetic backstory treatment which explains how they suffered some form of tragic circumstance which transformed them into the evil being they became. And it happens to be that I’m mostly against the tragic villain backstory as a storytelling device. I’m about to tell you why.

First let me give some credit where credit is due. In some of the old tales of speculative fiction, good and evil were often distilled out to the point where they became…well…really corny. The villainous laugh of the over-the-top baddie not only is a bit silly, it really hasn’t been all that common among historical bad guys (though if, say, Ivan the Terrible were to be laughing at you, you could be sure that you were in deep, deep, deep, deep trouble–so villainous laughter really has been “a thing” sometimes). Plus, isn’t it actually true that most people are a blend of good and evil impulses? Isn’t it fascinating to see a character who exemplifies both virtuous traits like courage and charisma while at the same time being a heartless butcher and abuser of oppressed people? (I’m thinking of you, Gul Dukat, Star Trek Deep Space Nine.)

Gul Dukat

Image Copyright: CBS

Yeah, in many ways, storytelling has become richer in certain aspects by exploring people who are shades of gray and by showing how circumstances can lead a person to switch from one side of the equation to the other…though even the cheesy Flash Gordon stories occasionally showed a good character tempted by evil or a bad character helping someone good. And The Lord of the Rings did this very well at times, showing dividing lines between good and evil in complex ways in places within the narrative, including how Frodo was drawn to evil by the power of the Ring, while Gollum was drawn back the other way.

So my objection to the modern villain’s tragic backstory is not that I’m protesting “gray” characters–at times such characters are very interesting (though I also like good and evil in purer versions at times, too). Nor am I objecting to characters shifting over time in either the direction of evil or the direction of good.

I am a bit put off by the presumption that people are by default good and something needs to happen to make them bad that I see in a tragic villain backstory. No, people in my belief and observation generally have both altruistic and also selfish impulses and while that doesn’t make everyone literally totally depraved (as in Five Point Calvinism) that does make all people helpless to expunge themselves of every form of selfishness by self-effort. People can get better by effort of will, but cannot get all the way good. You can find some few human beings in history who show nothing but utter contempt for other humans at all times, even though that’s quite rare. But I cannot think of any human being who has always been completely altruistic in all moments of life, not even Mother Theresa. In general, human beings round down to bad rather than up to good and in fact someone being a very good person requires a great deal of education and modeling of the example of others, not to mention an extra helping of natural empathy. All things considered, I would say that someone being very good requires more of a story explanation than someone being very bad–though getting this wrong is not what bothers me most about the tragic villain backstory.

What I most find offensive about a tale like Oz, The Great and Powerful, which shows the Wicked Witch of the West becoming evil because of romantic jealously, or Maleficent, which shows the wicked sorceress turn bad because of the a love interest who dies, or the recent Joker movie, which shows the villain (played by Joaquin Phoenix) as an emotionally fragile misfit who turns dark due to a series of slights and misfortunes, is the role these stories assign suffering. Suffering, hardship, something going wrong, someone abusing you–this is what these movies portray as producing evil.

Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker.

Image Credit: GeekTyrant

Why do I find that offensive? Well, not only because I have a rather tragic backstory myself in some ways (and I’m pretty sure I’m not a supervillain), but some of the greatest of all heroes are suffering heroes. Suffering can be the ultimate demonstration of love–Jesus Christ carrying the cross to the place of the skull–Frodo carrying the Ring up the slopes of Mount Doom–both barely able to move under the weight of their burden. Suffering can also deepen empathy and teach someone who never really had any tragic experiences how hard life is for some who walks in different shoes.

Suffering often drives people towards faith in God–many of the poorest and most suffering people in the world are also the most devoted to God, and often are very genuinely kind and gracious people. Yes, rough neighborhoods produce thugs, too, and poor countries can also be violent ones. Yes, sometimes suffering really does seem to harden people and make them worse than they otherwise would be. Yet passing through a great deal of suffering isn’t the most common profile of the scariest people who have ever lived on Planet Earth.

The scariest people on the planet are those willing to make others suffer, while avoiding all forms of hardship themselves. Yes, sometimes this sort of person is born into a rough neighborhood and looks around and notices that joining up with bad men will help protect him from harm–and he is willing to be cruel to others in order to avoid suffering hardship himself (using masculine pronouns because it’s almost always men who fall into this particular pattern of behavior).

But sometimes the worst of the worst are born into privilege and start life with inordinate power. Not having ever deeply suffered themselves, they view the suffering of others with contempt. Caligula and Nero grew up with this kind of power–and grew up in utter indifference to the hardship of others. Ivan the Terrible likewise, while he did suffer hardship and loss at times, was raised to believe he literally represented God on Earth. He believed for a time that he could do no wrong–he believed he was different from all other human beings–and that the lives and needs of other people were not as important as his wants, needs, and desires. Plus of course, some of the worst of the worst not only are poorly raised to see themselves as the center of the universe, they also lack natural empathy for a variety of reasons.

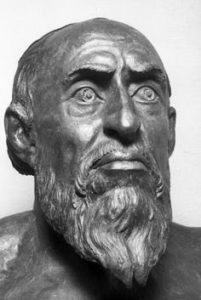

Ivan IV (the Terrible) of Russia. Forensic facial reconstruction by M.Gerasimov.

Note that I’m offering an opinion here about the true nature of evil, but I think it’s a solid one. The wickedness within the human heart springs forth far more when people are handed the power to damage others than when a person is helpless before the cruelty of other human beings. Helpless, suffering people may indeed become bitter and lash back, but normally, it’s those who are not themselves suffering, in an environment where suffering is commonplace, who have something to gain from making others hurt, who show the true depths of wickedness that our species is capable of.

Can I back up my opinion with science? To a degree, yes. Scientific studies on the nature of evil in general would be unethical, but one of the major ones that has taken place, the Stanford Prison Experiment conducted by Philip Zombardo in 1971, in which students were divided into two randomly-selected groups, one of which were prisoners and the other, prison guards, showed those in power turning sinister, not those suffering. Philip Zombardo in fact sees evil strictly in terms of this kind of environment of power imbalance as he explains in his book The Lucifer Effect—I disagree with him about that, because I see evil having multiple causes, but I do agree that an environment where people are given inordinate power over others who are suffering does far more to produce villains than people going through hardship themselves.

Historical events also have demonstrated how the seeds of evil in the human heart (through sin) sprout and grow in an environment of unlimited power over the lives of others. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn noted in his books on Soviet prison camps, The Gulag Archipelago, how guards in power routinely performed evil actions–though he also saw that an ideology justifying cruelty made people worse than power alone:

“The imagination and spiritual strength of Shakespeare’s evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses. Because they had no ideology. Ideology – that is what gives evildoing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others’ eyes…. That was how the agents of the Inquisition fortified their wills: by invoking Christianity; the conquerors of foreign lands, by extolling the grandeur of their Motherland; the colonizers, by civilization; the Nazis, by race; and the Jacobins (early and late), by equality, brotherhood, and the happiness of future generations…”— The Gulag Archipelago, Chapter 4, p. 173

But concerning his own suffering in the Gulag, Solzhenitsyn said: “Bless you prison, bless you for being in my life. For there, lying upon the rotting prison straw, I came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity as we are made to believe, but the maturity of the human soul.”

So if we as authors wish to portray ordinary people (commonly considered good, though they aren’t entirely) becoming blatantly evil because of circumstances, let’s pick the right circumstances. Tragedy and suffering are often ennobling. Whereas power over others made worse when backed by an ideology that justifies treating others cruelly–that is the sort of backstory that routinely cranks out villains. Not tragic events, not suffering and loss–not usually.

Some good points!

Good argument. Plus, you’ll never go wrong by quoting Solzhenitsyn.

Tragedy and suffering do not always ennoble. Solzheneitsyn, Viktor Frankl, and Corrie ten Boom told of people who quit acting like humans in the camps where they were placed.

There comes a point we must choose what we do with the suffering we have been dealt.

I like the novels Les Miserables and Anna Karenina. The “villains” Jalvert and Count Trotsky are complex. Jalvert overcame his tragic childhood by bootstrapping his way up. Not your typical villain though and not a maniacal sadist. He seeks the good but in the wrong way. Trotsky was a spoiled brat who always got what he wanted. Even if it belongs to someone else.

But these are literary. I think spec fiction should go more the LOTR and classic fairy tale route with villains.

I didn’t say suffering always ennobles. But I believe it often does. You would not realize suffering is ever good if all you did was watch modern speculative fiction movies give the backstories of villains…so I sought to counter the modern narrative that slights and sufferings are the royal road to creating villains…

The idea of a crossroads is a good one, though, and could work very well in spec fic. We all have those moments when we choose to turn toward darkness or toward light. No matter what our situation is, we choose. Of course, some go the route of inebriation, as a pretense of delaying the inevitable. Those are usually the “informant” characters.

Indeed, Rachel.

As I read your response, a song by Pat Terry – ‘Growing Up & Growing Old’ from his album ‘Film At Eleven’ – sprang to mind:

“It’s funny how pain can reach you

And it either makes you better

Or it robs you of your soul

All in all it defines the separation

Between growing up and growing old.”

Contemplatively,

PhiL >^•_•^<

It’s probably a matter of how the exact circumstances interplay with each person’s psychology. And maybe what nurture aspects they’ve had up until that point. Two people can have the same/similar circumstances and react in two different ways.

Something readers often do with tragic villain back stories is praise how sad the story is WITHOUT justifying the villain’s behavior. Like, they want to know the how’s and whys of the villain’s motivation, but they don’t want the story to say the villain’s actions are ok.

It’s also worth wondering what the exact definition of a villain or evil person is. Is it someone that has no good qualities about them at all/a lack of capacity for caring? There’s some pretty horrible people that have a capacity for caring, they just don’t use it. And if someone has no capacity to do something, can they really be blamed?

Conversely, if someone is ‘evil’ because of actions and such(regardless of how much they might care about others), exactly how many bad things do they have to do to be called evil? And are they really worse than someone that doesn’t usually do anything bad, but also holds contempt and indifference for everyone around him?

Sometimes it seems easier to call particular beliefs and behaviors evil, while describing people as ‘problematic’ or ‘harmful’ or some other thing. A full blown psychopath or a narcissist would be the closest thing to a truly evil person, I think. The only issue with that is people misdiagnose those disorders all the time (often just because someone upsets them enough), and true narcissists and psychopaths pretty much always end up that way due to factors outside their control. But, again, should we call people evil due to personal choices or because of who they are innately?

What do you think about the good intentions going awry thing (both in fiction and real life) because a lot of people try to do good and it ends up backfiring or hurting others in ways they’re too blind to see. Death Note is kind of like that, since Light’s idea was to use the Death Note to kill all the bad people so that only good ones were left/criminals would be too afraid to commit crimes. He had some selfish and arrogant motivations, but looking at some discussions of the show, some people actually support the guy, in spite of seeing how problematic he gets. So it actually is a realistic and important issue to explore.

A lot of times, though, whether or not it’s good intentions going awry or a villain having a tragic backstory, MOST people don’t say we should stop fighting villainous behavior, at least in real life. The reaction seems to be more like ‘I don’t care about your reasons, I just want you to stop hurting people!’

Yeah I think evil, while a bit hard to define at times, is for the most part identifiable in specific ways. Clearly not everyone agrees with me on that.

As for stories in which those who have good intentions go awry, yes, these can be quite interesting stories–and such events happen often enough in real life. But I think struggles between genuine evil and real good are more interesting.

I should warn you that the validity of the Stanford Prison Experiment is coming under fire nowadays. https://www.livescience.com/62832-stanford-prison-experiment-flawed.html

Scientific rigor would demand that we replicate the results many times, rather than relying on a single incident that involved a pretty small sample size of people (and replicating the SPE is obviously difficult for ethical reasons).

One thing that strikes me as missing from this article is a summary of what we know about the causes of things like bullying and domestic or sexual abuse. I’m not an expert on the topic, but I think there’s some evidence out there that abusers are more likely than average to have suffered abuse themselves. Suffering can increase empathy … OR it can lead the victims to hurt others in order to take back the power they feel they lost.

I do agree that suffering does not *force* anyone to commit evil. When we experience suffering, we get a choice in how we respond to it. But to me it does not seem implausible that some people react to suffering in terrible ways.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is what we have to work with because you can’t ethically perform experiments on people designed to make them evil.

Likewise since we cannot do double blind experiments to see what actually causes people to act in certain ways, we only have correlations between backgrounds and behaviors, which in a scientific sense doesn’t constitute proof. In other words, what is definitely known I would say is less than you seem to think.

I do not and did not reject the idea that suffering can cause people to do evil–but Nazi death camp guards (for example) weren’t drawn from those who were especially abused. Abuse is not required to form a bad person–examples from history very much argue the case I’m making.

I used to read true crime, I think because I wanted to understand why some people didn’t just go evil, but went evil in a bizarre twisted way. Serial killers tend to have missing/abusive fathers or abusive stepfathers. Knowing that helps, to an extent, make sense of behavior almost incomprehensible to most humans. But it doesn’t make sense of all of it because most abused children do not grow up to be serial killers. That kind of background could be interesting in a suspense novel, especially if it’s set against an investigator whose life trauma created the opposite impulse (justice), but it can be very ham-handed and unnecessary. Good article.

Thanks for your positive comment.

I know a few examples of historic people who suffered abuse who turned out very well–but in general, modern psychology is more interested in explaining people who commit horrible crimes than people who don’t commit them. That unintended bias of focus on cases where abuse produces monsters may be leaking its way into how villains are commonly thought of in modern stories…

Well, people who don’t commit horrible crimes aren’t exactly a problem and don’t need a solution, right?

But it’s part of the byzantine question of nature vs nurture.

I haven’t seen the Joker movie, but part of me thinks it will feel weirdly out of character. Like, something really bizarre and extreme would probably have to happen to make someone turn out like the Joker, so simply showing bits of injustice in Joker’s past isn’t going to be enough. The falling in a vat of toxic waste thing makes more sense, since the show could at least make a case for severe brain damage(which can greatly alter personality). Maybe I could buy the idea of extreme childhood abuse turning him that way as well, considering such things sometimes cause people to have NPD, but different types of abuse affect people in different ways.

Something people have to keep in mind is that he is usually depicted as having little to no empathy and that he just ‘wants to watch the world burn’. And that he hurts people for fun. Enduring injustice can make people do bad things, but probably not to Joker like levels.

The Joker found in the Dark Knight Batman movie was evil in the old style, just because, and as evil as the writers could imagine him.

The new Joker movie has a different goal–but even though I haven’t seen it, it already seems like the kind of thing that won’t ring true to me.

Just a side note to add to the possibilities, some people’s response to hardships and injustice is to withdraw, be mistrustful, etc. Or have a mixture of withdrawing while also becoming more compassionate and stuff, which is what tends to happen to me.

Yeah, agreed that an awful lot of abused people shut down in one way or other–which is quite different from lashing out and becoming Maleficent…

Yeah. I wasn’t ever abused, but that doesn’t mean dealing with people is easy. It’s understandable if an abused person does want to withdraw, though. It’s a much better alternative than getting vengeful.

Good post, Travis. Brought to mind some lines of poetry I heard this week from a pastor on the radio:

“But to every man there openeth,

A high way and a low,

And every mind decideth,

The way his soul shall go.

“One ship sails East,

And another West,

By the self-same winds that blow,

‘Tis the set of the sails

And not the gales,

That tells the way we go.” (from a poem by Ella Wheeler Wilcox)

There’s truth there, but in many respects we all are serial killers—but for the grace of God. That’s the real difference between those who do horrific deeds and those who don’t. That God has poured His grace on us for all these years to keep us from destroying one another is a provision we take for granted and in fact take to ourselves as if we are the ones who are setting a standard that treats others with kindness; only those who deviate are evil. Jesus called us out on this when He said, If you hate your brother it’s just as if you murdered him. Of course the world doesn’t recognize that standard, and sadly too often we Christians slide right by it. Maybe we ask, What actually is hate? Or some other dodge. I could say more, but I’ll leave it there.

Becky

A pleasure to make your acquaintance, Becky!

As I read the excerpt from Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s poem, something sprang to MY mind:

A song by Pat Terry entitled ‘Growing Up & Growing Old’ from his album ‘Film At Eleven.’

I daresay that these lyrics are the flip side of the same coin that Wilcox’s poem is on:

“It’s funny how pain can reach you

And it either makes you better

Or it robs you of your soul

All in all it defines the separation

Between growing up and growing old.”

Seen in this light, we cannot afford to take for granted the grace that God has poured on us, can we…..

Not even for a moment.

Because as soon as we start doing this…..

We’re setting our sails wrong, aren’t we?

Cordially,

PhiL >^•_•^<

It depends honestly. Darth Vader is richer for his tragic backstory, and even then his redemption is owning up to his mistakes.

Sometimes people don’t have tragic backstories but still turn out evil because of how they were raised. An asshole aristocrat who burns poor people in one manga is that way because society told him that he as a noble was above the law. Still satisfying when he’s tricked into publically confessing his crimes and decapitated