Refuting Universalism Slanders Of C.S. Lewis, Part 2

C.S. Lewis had some issues. Every Christian author has them, right? And we need not die on a hill to defend everything he wrote or believed any more than we ought to shun him and call him a heretic. Still, it would be sinful and slanderous to repeat things like “Lewis didn’t believe in the Biblical Hell” or “Lewis was a universalist” without reading reminders from those better informed about what the fantasy and nonfiction author wrote in his full body of work.

Last week I started with reminders that Lewis clearly stated in his nonfiction that he believed in a final punishment in Hell for those who refuse to repent of their evils. That’s indisputable. Call him fuzzy on why Christ died on the cross or on the Bible’s inerrancy, but he wasn’t universalist.

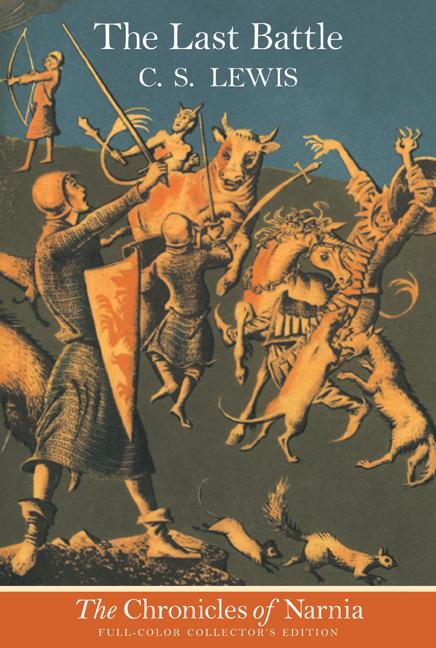

Now we come to one of the trickier issues: the seemingly strongest place, in Lewis’s fiction, in which he seemed to say you didn’t need to be “saved” to enter “heaven.” That is, in The Last Battle, Emeth, a “noble pagan,” did not at first believe in Aslan, yet still somehow crossed over from old Narnia into the lower parts of the new Narnia. Christians get confused about this, perhaps bypass it as a quirk; others use it to reject Lewis entirely as a heretic or universalist.

But readers ought to apply right “hermeneutics” to Lewis the same as we should with Scripture.

Reading Lewis rightly

Christians who profess to follow Scripture must remember how they’re meant to read the Word: mindful of the whole picture, seeking the original meaning of a text, and reading in context.

That’s hermeneutics. We should not salvage pieces of the Bible for alternate intents. Similarly, readers should not salvage Lewis quotes merely to prove him a false teacher or heretic, or to imply that he was Saint C.S. without any doctrine issues. Whether reading Lewis’s nonfiction or his fiction, we must stay mindful of the whole picture, following the genre’s rules.

This applies when answering this common accusation about Lewis’s beliefs: Lewis believed universalism, because in The Last Battle, a pagan character goes to heaven.

Another Scripture reading rule applies to Lewis’s works: clear parts interpret not-so-clear parts.

So if you’re reading The Last Battle and it seems to be showing universalism — that Emeth got into the paradise of Aslan’s Country even though he was a pagan — bear in mind that Lewis more clearly wrote elsewhere that universalism was a lie. That’s clear enough from The Problem of Pain. And in his allegorical story The Great Divorce he repudiated the notion by name.

So if you’re reading The Last Battle and it seems to be showing universalism — that Emeth got into the paradise of Aslan’s Country even though he was a pagan — bear in mind that Lewis more clearly wrote elsewhere that universalism was a lie. That’s clear enough from The Problem of Pain. And in his allegorical story The Great Divorce he repudiated the notion by name.

By contrast, the Emeth Element is more vague, and many other interpretations could be pulled from it. But none of them will make sense unless readers are willing to see that The Chronicles of Narnia are not meant to be allegorical, but a supposal. Lewis asked (and directly made known his mindset in several quotes) What would happen if God made another world, like Narnia, and Jesus appeared and acted there similarly to how He works in our world?

If Aslan represented the immaterial Deity in the same way in which the Giant Despair [from Pilgrim’s Progress] represents despair, he would be an allegorical figure. In reality however he is an invention giving and imaginary answer to the question “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?” This is not an allegory at all.

— The Letters of C.S. Lewis, page 283 (boldface emphasis added).

Thus in Narnia, salvation works differently. There’s no metanarrative of redemption throughout an Old and New Covenant, no sacraments of Communion or baptism, no official Church. Christian readers who try to find these ideas in Narnia will be frustrated — and worse, contradict the author’s intention, the same way we should avoid doing with the Bible itself.

Exploring with Emeth

Now let’s get this specific story straight. Emeth, a pagan but noble Calormene who devoted his life to service of the evil entity Tash, somehow makes his way into Aslan’s Country. But he’s in a kind of in-between status. There Aslan meets him and Emeth immediately repents, sorry he has lived all his life for Tash. Aslan, though, reassures Emeth that Aslan has nevertheless counted his good deeds as service to Aslan instead of Tash. Then Aslan leaves Emeth to ponder that.

Now let’s get this specific story straight. Emeth, a pagan but noble Calormene who devoted his life to service of the evil entity Tash, somehow makes his way into Aslan’s Country. But he’s in a kind of in-between status. There Aslan meets him and Emeth immediately repents, sorry he has lived all his life for Tash. Aslan, though, reassures Emeth that Aslan has nevertheless counted his good deeds as service to Aslan instead of Tash. Then Aslan leaves Emeth to ponder that.

Is Lewis hinting only that a nonbeliever could go to Narnian-style heaven? That’s one possible interpretation, but it has competition. For example, Isaac McPheeters suggested this about Emeth (he and I in 2009 also hosted a NarniaWeb podcast about the Emeth Element):

If you read what Emeth says, he’s talking not about people but about worship and actions that are good and evil. Nothing truly evil can give glory to God, and nothing truly good can ever be used in Satan’s service, no matter who might try and claim them. Besides, Lewis only gives a few examples of the process of salvation in the books. Shasta is sinful in the stories, yet he’s in Aslan’s country at the end. How? There’s nothing in the books alluding to Aslan’s sacrifice in [Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe] to be for anyone than Edmund. How is his blood paid for? In short, it’s not necessary for the purpose of the story. It would make the stories too convoluted if every character’s conversion experience was elaborated on in that way or if the process was explained ad nauseum.

But even if that’s not Lewis’s only intent with Emeth, some other idea is being shown here. What he says can’t be supporting universalism — not when we see happens just a few pages before. (‘Ware The Last Battle spoilers.) Aslan ends the first world of Narnia, and hordes of creatures rush to a gateway between that world and the next. And many of them fear and hate him. They turn away and are forever lost in “his huge black shadow.”

“The children never saw them again,” Lewis notes. “I don’t know what became of them.”

Is it heresy to humbly wonder or ask what-if?

Still, Lewis writes elsewhere of his wish that somehow, in some way, all people might be saved. Unlike some, I don’t automatically consider him beneath other Christians who might not have (or admit that they have!) the same secret wish. Yes, it may be a failing of Lewis, but if so it’s a failing common to us all because of our flawed awareness of how bad human sin is and how holy and just God is. Admitting our weakness is not sin. Wondering what-if-in-another-world is also not sinful, so long as we, in our hearts, love the truthful Gospel.

Does that secret hope or those what-if questions make someone a heretic? Not if they’re said out of ignorance and without willful rejection of clear Biblical truth. I seriously wonder if Lewis ever found either on this old Earth, and thus was open to other ideas — even while affirming enough of the Gospel to count for salvation: Christ died for my sins. More on that, next week.

Nice thoughts. Maybe some would say the sinner on the cross never accepted Jesus as his savior. He may have just been hedging his bets when he asked Jesus to remember him when he got in his kingdom. But Jesus knew his heart. And emmet could represent the billions to be resurrected into the kingdom, like those from Sodom who Jesus said will fare better in the resurrection than some of his day. Obviously millions will be resurrected, many of whom will still ultimately not accept Christ’s rule. I don’t see the problem with his scene at all.

Susanne, that’s a great point — one I may repeat in next week’s column. Also, the Old Testament saints were similarly saved because they were anticipating the coming Christ. With fuller exposure to Biblical revelation, Christians may rightfully insist that we shouldn’t hold back from studying all of Who God is and what Christ did. But for those who are somehow partway there — we know He is good and judges fairly. And evangelicals have rightly made similar arguments for the salvation of the unborn. (Again, more on this next week, especially as it pertains to the more-general question of how Christian speculative-fiction authors should hope to explore other-worlds while honoring the real-world Gospel. …)

And with that same what-if hypothetical argument, the Apostle Paul showed even more solidly the truth, if nothing else than by contrast, and yet also his very personal wish that God would save them somehow, despite what he knew to be true.

Whew, so very true. That’s a central reason I explore such topics in columns like this: because I learn so much from others!

Another thought: Paul also, in that same passage, even asked “what if” about the dreaded subject of “double predestination”! He even said “what if.” Must have been in a speculative mood that day (inspired by the Spirit, of course) …

Elsewhere in Scripture we read more certainly that man is responsible for his actions and meaningfully chooses to reject God and thereby embrace destruction. Also, God is not responsible for the evil of what happens. However, one can see that this part alone, separate from the rest of Scripture, could be used/abused to support an un-Biblical doctrine of fatalistic “hyper-Calvinism.” What-ifs must be kept in context!

Even Paul asked the “what if” in Romans 9. He said he would be willing to be cursed (cut off from Christ) if it would save his people, the people of Israel. But then Paul goes on to say that he knows not everyone will be saved.

As a child, I puzzled over this myself. I came to the conclusion after several re-readings that Lewis was not saying people who choose to worship false gods (i.e. Tash) and willfully reject the true God (i.e. Aslan) would be saved, but was pointing out that the glorious, terrible, wonderful god Emeth had longed for and been worshipping all along was in fact Aslan, even though his culture had taught him that those attributes belonged to Tash and that Aslan was the false god. But Emeth’s conduct even as an ostensible worshipper of Tash had been pleasing to Aslan, which showed that his heart longed for all the right things. And as soon as Emeth was presented with the true God in the form of Aslan, he recognized him and humbly repented of his errors at once.

So in that sense, Emeth didn’t come into Narnia as an unbeliever. His response to Aslan once he had seen him showed the true state of his heart as someone who loved goodness and humbly accepted his need for forgiveness and salvation (“I, who am but a dog…”), unlike those animals and men at the door judgment who looked Aslan straight in the face and then deliberately, arrogantly, turned away.

the glorious, terrible, wonderful god Emeth had longed for and been worshipping all along was in fact Aslan, even though his culture had taught him that those attributes belonged to Tash and that Aslan was the false god.

I first read Narnia in third or fourth grade, and the story of Emeth meant something to me then, but I wasn’t sure what. But you hit the nail on the head.

Yet our God is universal, inasmuch as God is the only God, creator of the universe. If it is the fault of flawed, hate-filled, judgmental “Christians” that some can not accept Jesus-because of His Misrepresentation through his so-called followers… Who is more likely to go to heaven? The self-righteous man who publicly claims to be Christian while boasting in his goodness, putting others down (searching for faults in others to declare them witches and heretics), yet lives out no demonstration of actual Faith in God; or the man who may be a deist, Buddhist, Muslim, or Other in identified religion, yet devotes his life in humble faith to the only God he knows to be good, prays to and worships, and does good deeds- not to be recognized, but to share the goodness of his God. God knows the heart. He knows who loves him- even if they are confused about who he is; and he knows who hates him (or love themselves more)- even if they masquerade as his own. I am not a universalist because I am sure there are many to whom God will say “I never knew you”- I just think we may be surprised at who we meet in Heaven. I thank God that He makes that decision and not us.

Stephen, Jesus had the wish that the Jews would all come to Him, so obviously such a wish is not sinful – Matt 23:37

Re. Emeth – I recently read in Acts 10 about Cornelius, “a devout man and one who feared God with all his household, and gave many alms to the Jewish people and prayed to God continually.” God heard his prayer, despite the fact that I’ve been taught (and taught) that sin separates us from God, that none of us seek after God. Yet when God appeared (or His angel) to Cornelius, here’s what happened

Not a Jew, not a Christian who had believed on Jesus’s name, yet God heard his prayers and accepted his offerings.

Then there was the eunuch who was reading but not understanding Scripture until Phillip came and explained it to him.

These instances and others make me believe that God makes a way for those who will come to Him. And He alone can be the judge of who that is.

Mayhaps we, myself especially, like things in an orderly, teachable format. The thing is, the Bible doesn’t always cooperate. 😀

And to the point of this post, should we excoriate Lewis for suggesting in fiction, through a “supposal” fantasy, something similar to what Cornelius lived?

Becky

Well said, Becky. And look, too, at all the examples in the Old Testament of those God called out of pagan societies and brought into the company of His people — like Rahab and Ruth, for instance. I remember discussing the issue of “What about people in other countries who haven’t heard the gospel?” with my mother as a child, and something she said stuck with me — “If they are faithful to the light they have, God will give them more.”

Someone in a pagan society may have only a tiny bit of light — just the realization that God exists and that He is the Creator, perhaps. But if they long to know more of Him and are willing to respond to any guidance and enlightenment He may give, then surely God in His grace will not deny them, any more than He denied Abraham or (as you mentioned) Cornelius?

Even Nebuchadnezzar, proud and evil man though he was, eventually came to a realization that God was the supreme Lord and acknowledged Him as such. God is far more patient and gracious with individuals than we humans sometimes give Him credit for — or than we would be inclined to be in His place.

But I think the real problem is that we want to take every individual example and make a hard and fast rule out of it so we can easily sort people into categories of good and bad, saved and unsaved, redeemed and irredeemable. Rather than allowing God to make that judgment out of His omniscience, we try to do it ourselves by outward observation. But only He knows the heart.

Ruth and Rahab (both ancestors of Jesus, no less) are good examples, RJ. But I’ll be honest, this makes me so very uncomfortable because I believe with all my heart what the Bible says: Jesus is the way, truth, life and no one comes to the Father but through Him.

In addition, I think some who might classify themselves as seekers or emergent thinkers point to the things we’re talking about and say, See, I can choose the Buddhist way to God if I want to.

I think nothing is further from the truth. Instead, I love what you said in your first comment (we were cross posting then 😉 ) about Emeth.

Becky

Yep, I absolutely agree that salvation is found in no one else (hm, I wonder where THAT quote comes from?) but Jesus Christ. If a person has been shown the truth about God and Christ as revealed in Scripture, but chooses to pursue their own way (or the Buddhist way or the Hindu way or the Wiccan way or the Choose-Your-Own-Mishmash-Of-Religious-Ideas way) instead, then they will be accountable for that and are without excuse. That would be akin to Emeth seeing Aslan face to face and then saying, “No, thanks, I prefer to continue rendering my services to Tash.”

But when I say that we can’t judge the heart, what I mean is that we don’t know to what extent any given individual has truly been enlightened about the way of salvation. They may have heard the gospel but not really understood it, or only heard a distorted version of it which is actually contrary to the truth. They may be headed in the right direction but not have reached enough of an awareness and understanding to repent and believe in Christ as Saviour — yet.

Or, on the other hand, they may have heard, understood, and willfully rejected the gospel, in which case there is no hope of salvation for them. But in most cases it’s impossible for us, simply by outward observation, to know in which state other people are really in. That’s why I’m glad that God knows the heart and that He is the one to judge the living and the dead, not me.

Which is not to say that we are not called upon to judge those IN the church if their conduct is persistently and unrepentantly wicked, but that’s another matter. I speak of those outside the church.

“If they are faithful to the light they have, God will give them more.”

That’s the thing – Emeth was not ‘saved’ because of the good things he did for Tash. In the end, Aslan did come to him, and Emeth accepted him. (I’m using Christian language here, though obviously it doesn’t really fit Narnia)

Have you ever read a book called Mimosa by Amy Carmichael? It’s a true story of a little Hindu girl who heard one day of the God who loves her. Despite knowing nothing more, she decided he would be her God. I think she was very like Cornelius.

Is it possible that since this WAS Narnia’s apocalypse, and Emeth, strictly speaking, was not quite “dead” yet, and believed in Aslan? Might he not be similar to those whom, depending on one’s view of eschatology, sees becomes saved at the end of days? I mean, if people will be saved at the end of our present world, as the Bible teaches, some may be saved due to the knowledge they have of the truth, and realize it is the truth. Emeth obviously knew who Aslan was. Might he not have instantly repented at the sight of the Lion. If I was in his shoes, perhaps I would have done so.

If he were dead, that is one thing, but since his experience occurred BEFORE Narnia’s version of separating the sheep and the goats, if he were alive, might this not work? Perhaps he simply does represent the idea of those who will believe at the end.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Timothy Stone, E. Stephen Burnett. E. Stephen Burnett said: Name-checked @TheCultureGrid/@Prince_Rilian today on #SpecFaith about C.S. Lewis and universalism: http://bit.ly/e9mHFd […]

Thanks for doing these!

Who can or will God save? Since He is entirely Just and Holy, and holds the councils of Eternity within Himself, I will only mildly speculate that He can and will save whomsoever He desires but how He does that, I mean the intricacies apart from the revelation of Jesus Christ, remains a mystery.

How God saves the pagans, I am speaking from a Reformed perspective, is the same that He saves anyone; within His own Divine foreknowledge and Election. God orchestrated those events that lead the spies to Rahab, that caused Ruth to cling to Naomi and return to the Promised Land, and even lead to Cornelius’ prayers and faith in whom he knew not.

“Acts 17:30

And the times of this ignorance God winked at; but now commandeth all men every where to repent:”

Who is the name they must repent and believe in? Jesus, for there is no other name given under Heaven whereby men must be saved.

How do they believe except by hearing the word preached unto them? ( romans 10:14 ) I heard an interesting theory one time reconciling God’s election and predestination of the heathen scattered throughout the world. Is is that hard to imagine that God would place those who will be saved in a place and time that they can hear the gospel and believe? That if they are ” faithful to the light they have ” He will send someone with a fuller knowledge and revelation of who Jesus Christ is.

As to Emeth, can God not save who He will at any time He will? Even in the supposal fiction of Narnia is not salvation the perogative of Aslan? If Emeth only truly believed for a minute in time is he still not deserving of eternity as much as the ones who labored for a lifetime? ( Matthew 20:11-13 )

Exactly Sir. If he was still alive, and saw Aslan and believed, then he would be “saved” just as much as in our world in relation to Christ. If he WAS still alive, and believed upon seeing Aslan, would that not be enough?

[…] them! Still, I’d challenge such Christians to survey the contents of this series’ parts one and two, attacking the notion that Lewis was a heretic and/or accepted […]

I know this is an old post, but I have to note the salient fact of Emeth’s story: he *met* Aslan, *repented,* and went on to *serve him.*

[…] fantasies are not to be feared as heretical or “rewrites” of Christianity. In the second article in his series, Stephen specifically addressed the scene from The Last Battle that Schnelbach […]

Nero-posting here but there’s something else about the Emeth dialog that always bothered me. I get the debate about whether the character were still alive or not when confronted by Aslan and possibly being viewed as repenting thus being saved. However, this does not appear to be Lewis’s intent. He specifically regards the good deeds done for Tash as being done for Aslan. In another writing, Lewis specifically took this from the scripture where it says evil cannot be from God and he’s the father of all good things (memory here, so that’s a major paraphrase). However in context of this part of the Narnia story, this means Aslan told Emeth that he was effectively saved by works. Salvation by works is also in stark contrast with scripture.

Was Emeth repentant? It looks like he may have been but regardless, the reason given for his entry into heaven was misplaced. We will indeed be rewarded for our stewardship but it is most certainly not the means of salvation. I feel like C.S. Lewis understood this but made an oversight when writing this book to try and make another scriptural point. It should not have been used in context of salvation.

I meant “necro-posting” not Nero-posting 🤣