How To Be A Silly Christian Fiction Critic

Different kinds of critics filled the world, surprisingly enough even before the internet.

I count at least four kinds: constructive critics, trolls, silly cheerleaders, and silly critics.

Delightfully, Anton Ego is proven a serious and constructive critic by the Pixar film Ratatouille’s end.

Naturally I want to encourage the constructive critics, and hope to remember “don’t feed the trolls.” And I want to chide the final two groups of “critics,” especially when they cross onto our enjoyments of God-exalting stories (speculative and otherwise).

Here’s how I define those final two groups:

- Silly cheerleaders — Rah rah rah! Yay Christian fiction! It’s like the fiction you love, only, you know, Christian. No, the story style and craft don’t really matter. Stop being so elitist. After all, God Himself didn’t give His own Story with the best craft and genre diversity and most wonderful style in the world — all that matters is the Content.

We often challenge silly cheerleaders at Spec-Faith. So I feel free to address only:

- Silly critics — Christian fiction sucks. It’s not reaching people. It’s not Realistic and Artistically Excellent and too often offers Easy Resolutions that gloss over suffering and nastiness. Look at the success of “secular” fiction. When will Christians achieve that?

What am I to do? Criticize silly critics? Not at all. I want to be a positive speculative-story explorer. I cannot curse the darkness without lighting candles. Naturally I present:

Seven Ways to Be A Silly Christian Fiction Critic

1. Don’t read the actual books.

One can’t become a silly critic who bashes all available Christian fiction by actually reading all available Christian fiction — which includes not only the stuff found on Christian store shelves, but independent publishers and even self-publishers. Limit your reading choices.

2. Compare Christian fiction’s most popular novels to the best literary novels.

You must be casually aware of Christian fiction’s dominant genre and/or authors, and set those in your mind against the (real or perceived) dominance of Classic Works written by Christians past or present. Result: “Oh dear, oh dear, why are Christian readers favoring books with titles like Amish White Christmas Pie instead of the value of a Flannery O’Connor short story?” But you cannot carry out this criticism without subconscious belief that:

You must be casually aware of Christian fiction’s dominant genre and/or authors, and set those in your mind against the (real or perceived) dominance of Classic Works written by Christians past or present. Result: “Oh dear, oh dear, why are Christian readers favoring books with titles like Amish White Christmas Pie instead of the value of a Flannery O’Connor short story?” But you cannot carry out this criticism without subconscious belief that:

3. “High culture” is better than “low culture.”

As author Ted Turnau points out in Popologetics, many Christians accept (or suspect they must accept) an elitist notion that “words are better than images” or that “this music genre is simply better than that music genre.” Accept this dichotomy. Really, Christians should not be reading or writing “popular” level novels anyway; we should only read the best classic novels. (We must also avoid reading Turnau’s annoying and Biblical rebuttal of this view.)

4. Avoid recalling the “bad” Christian stories you may (have) truly enjoy(ed).

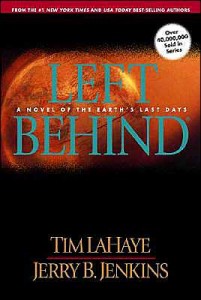

Did you read, say, the Left Behind series? Did the Holy Spirit use even that questionable-eschatology-filled, seemingly-never-to-end thriller franchise in your life? Well then, isn’t He an idiot. The Holy Spirit doesn’t know excellent Art and can’t possibly use it to help anyone.

5. Avoid asking, “What exactly would change my opinion?”.

It’s much easier to keep one’s standards vague and floatey than to put them in writing. What exactly makes for “bad Christian fiction” over and above “bad secular fiction”? What is the mathematical ratio? Twenty parts bad to one part good = all bad? If there are but ten righteous in the city of Christian fiction, shall we spare the industry for their sake?

No, of course not. After all, all these other secular critics are not impressed with Christian fiction (for whatever reasons, genuine or otherwise). And we do want to show them that Christians can be artistically cool and also agree that the Church sucks, do we not?

Actual cures? Those can come later, after just one more blog re-re-re-identifying the illness.

But if you do happen to think about exactly what would cure this disease, then you must:

6. Offer yourself and your idea for another novel/publisher/universe as superior.

Who else to reverse the course of history and finally Take This Town for Christ than us?

Finally, this seventh point is the most vital to being a reflexive, silly Christian fiction critic:

7. Don’t challenge your silent acceptance of evangelical change-the-world tropes.

Many evangelical readers, authors, and publishers seem to think something like this:

Many evangelical readers, authors, and publishers seem to think something like this:

We must change the world through our fiction. Story’s purpose is not to glorify God by exploring beauties and truths of Himself, people, and His creation. Instead story’s purpose is to entertain, or evangelize, or morally edify, and Change the World.

So as a silly Christian fiction critic, you are bound to respond:

Yes, oh evangelical fiction industry, your core assumptions are exactly correct.

Your only problem is: you’re doing it wrong.

Your stories must be more entertaining, and not so “cleaned up.” That way you’ll be able to do evangelism better, and will not put people off Christianity.

Also, in all your moral edification — family values and patriotism and anti-abortion are nice, but they’re also very off-putting. Let’s have more stories about the values I support, such as challenging intolerance or hatred of gays, or caring for the poor, or even squishy beliefs like ecumenism or universalism.

Maintain this line. Never give up, never surrender. Never consider whether subpar stories result because of these assumptions, not despite them. Never consider what Scripture says about great stories: that they’re not for its own sake, or ours, but to reflect our Author.

I very much agree with #2. I think Amish romance getting the shaft as being the major part of CBA fiction is unfair. We then need to look at secular fiction and face the fact that something like 60% of it is category romance as well. The CBA has bonnets, the ABA has sex. I don’t read either, but I really, really doubt the level of craft is terribly different for the two–in this case, the main difference is content.

To truly compare the CBA and ABA we have to look at *percentages* because the CBA is simply smaller. What percent of books in the CBA are of really high quality vs average quality vs really low quality? My guess–based on what I’ve seen–is that it’s a bell curve for both. It’s just that the ABA curve reflects an overall higher number of books.

That said, the curve may get skewed because the CBA doesn’t have *as much room* for some of the books outside the mainstream. Spec fic writers and those who write more literary or gritty works find the CBA door locked and end up either self-publishing, or going to small presses or ABA presses. So it’s out there, but it’s not being classified with true CBA works. And that is where the legitimate critique comes in. It should NOT be about what already exists in the CBA. That stuff has an audience and has every right to be there. It should be focused on making room for more diverse works.

Reluctantly I agree. As Rebecca Miller wrote after the post that inspired this one:

That was in response to my quick comment:

Ok, help me out here. I’m interested in reading Christian speculative fiction, but I’m really picky. I generally read what’s classified as ‘new grit’ or ‘new weird’. I like books with more adult themes because I’m an adult. For example, if we’re talking movies, I generally prefer something with an R-rating, because I’m more likely to be mentally or even morally stimulated, whereas in most PG-13’s I’m likely to get cheap jokes and green screens. This is what I’m afraid of in stepping back (for the first time since jr. high school) into the world of Christian fiction. With mostly adult-oriented content off the menu, am I going to be stuck with Michael Bay/Nicholas Sparks gimmicks? I’m sure there’s good stuff in the Christian speculative fiction world, but I have no idea where to start.

Jon, check out Brian Godawa, Ted Dekker, Vox Day and Marc Schooley for starters. Not sure if that’s exactly what you’re looking for, but between them they cover a range of speculative and suspense.

Funny thing, I tend to prefer a grownup presentation as well. 🙂

(Been trying to post this for a few hours now; not sure what’s wrong with the blog software. Meanwhile, it so happens that Schooley’s writing partner shows up first.)

Disclosure 1: I’m not intrinsically opposed to, say, R-rated movies or similar fiction. I just haven’t found any that I appreciated — they’re either raunchy comedy that does not entertain me and doesn’t lead to joy, or else (to me) the kind of “gritty” stuff that also doesn’t lead to joy. If it doesn’t bring me joy, I’m not interested.

Disclosure 2: I view the “chief end” of fiction, the only reason we should enjoy stories or any kind of art, as this: to help us glorify God and enjoy Him forever. And by “glorify God,” I mean explore more His truths, beauties, goodness — Himself.

I like YA like Harry Potter and The Hunger Games, and of course classic “children’s” fantasy such as the Narnia series. These often carry more timeless themes and honesty about heroism and the human condition. The “gritty” stuff I’ve seen (if I’m thinking of what you’re thinking about) often errs in the exact-opposite direction from the anti-realism of sappy, sentimental fiction, Christian and otherwise.

His Abysmal Sublimity Screwtape gave the best example of how to use expectations of “grit” and “real life” to tempt human patients toward the darker side.

Plenty of good Christian novels, however, many of them from the “indie” side of things, offer a kind of enhanced “grit” and/or horror that fits within a Christian worldview, exploring darkness yet with balancing, victorious Light always just out of sight. The best one I’ve read so far is the paranormal/historical fantasy Konig’s Fire by Marc Schooley. More about it is here, and my positive review is here.

I agree with both Jon R and E. Stephen Burnett. I think there are terrible stereotypes on both sides of the “grit” argument. Lack of “grit” does not make a work cliche, petty, unchallenging, or childish (whether or not written for children). Presence of “grit” does not necessarily make a work angsty, elitist, or immoral.

John R wrote:

Agreed that the “New Gritty” can produce works that are genuinely stimulating and challenging in a way that can be very positive.

Case in point: For me, watching through the newer Battlestar Galactica series via streaming has been a generally good experience. The show is very dark, very realistic, and completely honest about human evil. It has very explicit religious and political themes. The combination of the themes and gritty realism in the space opera epic-style plot make for great storytelling. We see people struggling for faith and hope in the face of devastation, and the joy and mystery comes from wondering just how grace and providence will prevail even through the horrors and the characters many sins.

Conveniently, Battlestar Galactica offers an opportunity to critique the limitations and bad tropes of the “New Gritty.” There’s sex in it. I don’t like it, even though I don’t really care to pass moral judgements on content rather than the work as a whole. The sex in Battlestar Galactica is a lot like the sex in a lot of secular film — it’s a lazy way to show that two characters are in love without developing their relationship, because unbelievers think romance=sex. The sex trope is really a secular cliche on the same level as the Christian cliche of having unbelievers swoon with giddiness when they hear that God loves them. Both are sentimental and untrue.

E. Stephen Burnett wrote:

I agree that the best children’s stories are very timeless. They don’t carry the baggage of social concerns that adult audiences are concerned with. However, as wonderful as the sense of timelessness is, I don’t think it’s the only legitimate quality in storytelling. Hamlet is not really timeless in the same way that The Chronicles of Narnia is, and it even has a fair amount of “grit.” (There are lots of subtle sexual innuendoes, for one thing.) You can’t get much more classic than Shakespeare, but he obviously was writing for adults, with all the gritty baggage of adult concerns.

I think the grit thing is partially just preference, it’s a good point from Screwtape that the good in life is just as real as the bad. I generally read fiction for the entertainment value, and if it causes me to think edifying things that’s a big bonus. While the gritty stuff doesn’t bring obvious joy for most (healthy) people, I’d say it can bring joy in that the grit is usually a result of some aspect of sin, the fall and the curse. In that respect, even grit can be God-glorifying if it causes the reader to appreciate God’s holiness by being able to more accurately understand the effects of straying from that holiness. The more perfectly you understand cancer the greater you appreciate a cure, right? In that sense, some of my favorite novels offer nothing in the way of hope or joy, but they cause me to look at the scenarios through a biblical lense, and appreciate the delicate balance of God’s common graces in the midst of a fallen world. The whole Old Testament for that matter is gritty. It’s the great conflict, followed by a series of failed attempts by man at a resolution. ‘Can man be saved?’ ‘No, man is a murderer’, ‘no some guys wander around the desert’, ‘no, let’s have a beauty contest’, ‘no, throw me into the ocean!’, and then finally Jesus came and answered the question. The darker the tunnel the brighter the light at the end. For me, knowing the truth of the light at the end means that even if the author doesn’t, the tunnel can also bring glory to God. Still, I’m interested in taking a look at that book you suggested. Cheers!

Stephen, I had trouble posting the other day as well, and couldn’t leave a second comment. Thank you for the disclosure note…I work with Marc from time to time.

As a matter of reverse disclosure, I’m not particularly a fan of Vox Day (so far), iffy on Dekker, and should have mentioned Robert Liparulo. He is freakin’ fantastic.

Seriously? I can hardly believe this statement. All of literature must submit itself to this criteria? So zip on entertainment?

Was I supposed to draw deep spiritual lessons from Ender’s Game, or not read it? How about Hunger Games? All The Pretty Horses? The Road? Beloved? Surely, there was deep beauty and truth in The History of Love and Gilead, but how was I supposed to know that before I read them? How about any of Edward P. Jones’ works of breathtaking beauty? Am I wrong to love a writer for his beautiful, skillful prose if he doesn’t glorify God?

The apparent dilemma begins to be solved this way:

So, without lapsing into fatalism (man is still responsible for using God’s gifts to write for selfish ends), this may help clarify that definition of “glory,” and head off the “overt Christian Content only” definitions of the same.

As suggested here, God will get glory in at least three ways: over an action, through an action, or by contrast with the action (e.g., if I read a bad story, He still gets glory because I’m motivated to say, “Thank You, God, that You ensure all our stories aren’t this horrible”).

In other words, an author may not be worshiping God. But I would be.

And even if I’m not thinking Specific Christian Thoughts while enjoying a story, as a redeemed saint I in turn can help “redeem” whatever I touch.

Thanks so much for the reply. It helps a lot, and reminds me to give thanks to God for all His blessings.

Hi Jon, I wish I had an answer for you, but I read PG stuff. I get tired of sex, cursing and homosexuality being thrust at me whether I want it or not, so I only write/read PG-13. You may have to do some searching to find it. Most Christian authors stay in PG-13 b/c it’s what their audience wants and what God wants. I know Marcher Lord has a more ‘rougher’ section, but I haven’t read them so I’m not sure what they are like. Check out Jeff Gerke’s website, Marcher Lord. He might have something for you.

Whoa there, hombre. “What God wants” is PG-13 or lower? I don’t know if you are aware of how sanctimonious that comes off as. You have your personal preferences, but some of us have higher thresholds.

MPAA ratings are not based on the Christian worldview. All I need is this:

I’m against grit-for-its-own-sake or elusively-grit, for the same reason I dislike the mindset behind many Thomas Kinkade painting fans: it’s imbalanced, one-sided. Yet leaning toward “G ratings” or “PG ratings” would rule out much of Scripture. But anyway, that’s a different topic or series from this one.

However, I would continue that discussion not on the topic of Content Ratings or How Much Is Too Much, but by asking (as is my wont): What is the purpose of a story? Is it only to entertain, edify, or evangelize? Or a greater purpose?

I’m with you on the greater purpose thing. Although I agree that the greatest purpose — the ultimate purpose — is to glorify God, I

Hi Kim, I appreciate your thoughts on this. Grits great, because it more often touches on the deeper deficiencies that mark our fallen nature, but I’ve enjoyed a lot of compelling storytelling that doesn’t include that. Toy Story 3 was one I enjoyed immensely for it’s themes. It just seems like that kind of movie or book is so rare. I grew up with parents who were of a similar mindset as you are presenting, so I certainly respect what you are saying. At the same time, Judges-II Chronicles, would have to be R-rated, just a thought. Thanks for the recommendation.

Pat Todoroff’s Running Black is a good book that doesn’t really pull any punches. I usually compare him to Bruce Sterling. Mark Carver who posts here now and then is pretty intense in his books. Rachel Starr Thomson is very good, as well. David Alderman is a friend who Black Earth trilogy is a bit rough, but has a strong anime-meets-Stand vibe to it.

Rick Macey is good. Elemental by Emily White is also good. There are books out there that push the edges some, but they tend to be hard to find.

Wow, so our reviews aren’t allowed to compare new Christian fiction books with secular books in the same genre? Doesn’t that lead to even more severe cloistering, since CBA is so much smaller? Recently someone did a Facebook poll of what was the last secular book people had read, and some said they hadn’t read a secular book in years. I was horrified.

Yes, if anyone writes such a review on Speculative Faith, it will be banned.

😛

But! seriously. My point was that it’s absurd to compare the worst of Christian fiction to the best literary classics, perhaps even outside the genre, and which are either “Christian” or “secular”). This is an apples-to-oranges comparison. And at best it smacks of that low-versus-high-culture divide mentioned in no. 3.

Horrifying indeed.

Given that kind of preference, however, I’d guarantee this person has simply been reading at least several secular books that have been marketed as “Christian” books.

LOL!! Like comparing the worst written book to a Dickens novel. Now that’s sad!! I’ve learned that what I see as ‘badly written’, someone else sees as amazing. I know of a very dear woman who self-published a novel that is full of info dumping, head popping, things that make your head spin like the girl in Exorcist, but everyone loves her stuff!! So I’ve learned that some writers might not ‘be’ there yet, but someone out there likes their books. Do the best you can, that’s all. I mean, why must we, believers in Christ, be so pumped up with arrogance as to tell another writer, your stuff sucks and is nothing like the Tolkien or some other great writer. I think writers are really the only ones who are super picky and enjoy destroying other writers who are trying to create great books. Why not, instead of being so critical, HELP writers learn technique? Why not start a writer’s group to help others? Why be so critical in claiming, it all suuuuccckkksss!!

So we’re supposed to be okay with mediocrity within Christendom just because the world tends toward mediocrity as well? That’s a profoundly unconvincing argument — like saying we shouldn’t be concerned about the divorce rate among Christian couples because, after all, non-Christians divorce each other just as often.

Last I checked, Christians are supposed to aspire to a standard higher than whatever happens to constitute “average.” We shouldn’t be using the Bell Curve as an excuse. And we shouldn’t be measuring our sufficiency by the yardstick of the world. Regardless of a book’s content or target audience — whether it’s a profoundly philosophical work of sci-fi “literature” or a whiz-bang foray into sensationalistic space opera — if it’s bold enough to boast of its “Christian” nature, no one should ever be able to honestly criticize it as “poorly written” or “poorly constructed.”

Not my thought.

Instead, I recommend we improve the fairness and quality of our criticism.

If one finds at least ten righteous novels in the city of Christian-fiction-dom, we might in one sense “spare” the industry for their sake.

Otherwise we come across as indiscriminate bashers, “me too”-ing secular critics.

For my part, I simply cannot impose such a high standard, at least not realistically.

Doesn’t this comes close to an over-realized eschatology? Surely even in the New Earth we’ll have some clunker novels published (though with absolutely no sin in them or in their authors’ motives). So why expect in any sense that standard here?

I’m happy to get any great stories from any source, “Christian”-labeled or not.

I said nothing about abandoning or condemning the Christian-fiction industry just ’cause it doesn’t live up to its potential. What I’m saying is that we should by no means cease spurring each other on toward good deeds (of art) by complacently pointing out with regard to poor writing that “everyone does it.” I’m sorry, but that’s not an excuse. Just as I’d never be able to justify getting divorced merely by appealing to statistics, I likewise can’t cut mediocre Christian authors even a single inch of slack for no reason other than the fact that “people aren’t perfect.” A book doesn’t have to be perfect to be excellent, admirable, and praiseworthy.

Again, one hundred percent agreed.

I hope I’ve stressed this enough in another columns — and it’s a major reason Spec-Faith even exists — to buy enough “karma” to explore another issue: the issue of indiscriminate bashing. But, taking my own advice, I certainly don’t condemn all criticism of Christian fiction, even the majority of the fiction, as indiscriminate bashing. Often the sorts of bashing I’ve noticed comes from folks who, in essence, consider themselves holier-than-thou than other Christians and even the idea of local churches. They’d be the same sorts eager to “apologize” for the purported intolerance of other believers, but not so much on behalf of other pagans, much less for their own personal sins and self-righteousnesses.

I point this out not to say “all indiscriminate Christian-fiction bashers are like this,” but to say, “A lot of this indiscriminate bashing comes from this sort of view of the Church and local churches and other brothers and sisters in Christ.”

Then encourage the knee-jerk naysayers to read more, read more, read more, and recommend specific titles that exhibit excellent craft. Cynics will never allow themselves to be nagged into the fold; they must instead be wooed. But your post doesn’t do that. In fact, it seems to imply rather heavily that the Christian spec-fic subgenre has been subjected to a disproportionate and unhealthy critical pummeling. But nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, the relatively cloistered nature of this subgenre’s niche market tends to insulate its authors from the cold, hard, dispassionate dissection endured by participants in the mainstream publishing industry. Yes, yes — cheap vampire romances are a dime a dozen in the larger market, but, thanks to withering criticism, they’re almost universally recognized for what they are: shallow escapism. I don’t see the same kind of relentless quality-control in Christian spec-fic circles. It seems to me that a majority of those who run in said circles (pun unintentional yet not without relevance) are so desperate for “Christian” stories that they’re willing to excuse almost any shortcoming of craft or style. My brother, this thing ought not be so. As those who aspire not merely to sell books but also to glorify the God Who tells the greatest story of all, we should be doubly committed to standards higher than anything the world might use to judge us. This endless quest for skapegoats — “The genre’s too young to exhibit much quality,” “The world publishes crap, so we should expect crap from our own authors too,” “Christian readers who badmouth our genre are silly critics” — has got to stop. We write as unto the Lord God Almighty, not as unto mere mortals. Nothing but excellence should satisfy us.

Excellence has to be defined in the real world though. The type of silly critic he means pans Christian fiction or holds it to a standard that has no real way of being met. “Write better than the unbelievers,” how? How exactly are the novels bad, and what aspects can be improved?

Ugh. I hear ya, D.M. But the problem with moving from general to specific criticism is that it’ll require me to actually finish a Christian spec-fic book not written by Lewis or Peretti. I’m working on it. The one through which I’m currently dragging myself got so unbelievably boring in its second act that I took a three-week sabbatical to reread a 1,700-page opus from one of my favorite secular authors.

I think the bottom line with regard to quality is that the stories of the best Christian authors should be at least as riveting at those of the best secular authors. The “Christianity” of these stories should be thought of as a welcome bonus instead of as the central conceit which makes them worthwhile in the first place. The latter kind of thinking leads to hubris of the worst sort: the “My-work-deserves-support-and-acclaim-because-I’m-doing-it-for-God” sort.

Note that I’m making allowance for the Bell Curve, here. I’m not saying that I expect all Christian spec-fic to be excellent (although no author has a excuse to settle for anything less); I’m saying that the best Christian spec-fic should be easily comparable to the best secular spec-fic. But I ask you: is that the case? I can name dozens of supremely excellent contemporary secular spec-fic authors off the top of my head. And in the Christian corner, we have … Frank Peretti in his early years. Stephen Lawhead doesn’t really count, as I can name several “secular” authors who write stuff that’s more “Christian” than his stuff. Perhaps I’m just blind. Perhaps I need to get out more. But so far, my experience with the SpecFaith library hasn’t been encouraging.

Austin, you brought in an interesting word here, one that gets tossed about in the grit/no grit conversation. But it doesn’t really refer to grit, so:

Can I ask you what’s your definition of “riveting”?

I know what mine is, and it doesn’t fit in the sentence “riveting romance,” as I’ve seen here and there at times in Christian circles. Just no.

Do you think it’s a subjective thing — based on what compels us personally — or an objective one, or maybe some blend of the two?

Ultimately, every adjective used to describe art is subjective, at least from a human perspective. But what I mean when I say a story is “riveting” is that it arrests and holds my attention. The verb form of “rivet” can be defined as “to attract and completely engross” (New Oxford American Dictionary). You’re right when you say that this artistic quality has little or nothing to do with a story’s “grit”: graphic descriptions of violence, gore, sex, sin, corruption, and general depravity can be just as dull or repellant as any work of sanitized didacticism. After all, if I as a reader get turned off and end up walking away from any given story for any reason, then that story has failed to rivet me.

Personally, I’m riveted by a story when I care deeply about what happens to its characters. And I only care about them when I respect them. And I can’t respect them unless I understand them and empathize with their thoughts, feelings, and motivations. But if I don’t understand why they do what they do, or if I think they’re implausibly stupid for doing it, or (worst of all) if I’m forced to watch as they passively do nothing, content to merely react to an agenda set by others, I quickly lose interest in the account of their lives.

In that sense, there’s nothing necessarily oxymoronic about the phrase “riveting romance.” Am I riveted by the slow-circling verbal dances of Jane Eyre and Mr. Rochester? You betcha. Am I emotionally invested in the tenuous, tumultuous courtship of Kvothe and Denna in The Kingkiller Chronicle? Of course. Do I cringe at every setback endured by Miles Vorkosigan in his pursuit of Ekaterin in Komarr and A Civil Campaign? I’d need to check myself for a pulse if I didn’t. None of these examples are “romance novels,” of course — I wouldn’t have read them if they were. Their genres are, in order: gothic drama, space opera, and epic fantasy. For each of them, romance is a side dish instead of a main course. But the romance itself was riveting because the characters had become my friends. I couldn’t have walked away from them had I tried.

Agreed, the romantic storyline can be riveting. I was thinking of the genre of category romance, for my part.

Personally, I’m riveted by a story when I care deeply about what happens to its characters. And I only care about them when I respect them. And I can’t respect them unless I understand them and empathize with their thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

So, looking through the totality of your remarks, then, what I’m getting is that you don’t find affinity with and respect for many of the Christian fiction characters you’ve encountered. The word “mediocrity” came up–so, mediocrity of personality, motivations and actions.

That has a lot to do with my refusal to read category romance, because I feel like the characters are shaped around the HEA plot requirement and the formula for getting there. Often, they do implausible things just as a matter of keeping them on the rails in the midsection of interpersonal conflict/attraction. In real life, they’d just quit talking to each other and go find real happiness. 🙂 The better writers know how to avoid shoehorning, but it’s been a fairly common thing in both Christian and secular romance.

From time to time, I sit back and muse over the brief history of evangelical Bible publishers producing fiction (1974-present…not much time compared to New York publishing or the Gutenberg press). It was built by romance writers, originally, by women who didn’t want to write smut. I can applaud that.

But I sometimes wonder how much those romance genre conventions initially shaped the way faith was handled in story — as ESB points out, it’s changed some over the last 10 years, and I’ve seen the internet accelerate those changes over the last 3-5 years. Shaping a faith storyline around the HEA genre convention almost necessarily leads to mediocrity of character, a strained plot, and an unrealistic, escapist conclusion. It also leads to a genre of faith fiction known for placing its message agenda above quality of story.

The problem I see with the silly criticism types I’ve encountered (not you, ftr) is that they aren’t willing to look at the scope and context of the problems, so they also miss the new developments and successes. It could be truly constructive to discuss how the conventions of one genre don’t function for readers of other genres. Or how those conventions shouldn’t have undue influence on our treatment of faith in story.

Your Specific Theory of Mediocrity seems plausible to me, C.L. However, I think it fails to account for the likes of us here on this blog, most of whom (myself included) are writers, many of whom (myself not included) are published authors, and some of whom I’ve read. I sincerely doubt that the same writers so quick to shuck off even a garment tainted by the incongruous perfume of Amish romance would feel obligated — even subconsciously — to adhere to its tropes.

I could be wrong, but it seems to me that the majority of those in this Christian spec-fic community have deliberately avoided the subgenre of Amish romance for the duration of their reading lives. So how, if that’s indeed the case, could they possibly be influenced thereby? Tolkien and Lewis and Peretti — them I can visualize wielding influence. It also wouldn’t surprise me to see Christian fiction writers attempting to copy Lawhead or Brouwer or Dekker (though I wish they wouldn’t copy the latter, now that he’s driven right off the cliff as a storyteller). But HEA genre romance as a trend-setter? That just wouldn’t make sense to me.

As for the mediocrity itself, I think that yes, deficient character-construction is probably the primary culprit. But it’s so much more (or should I say less?) than that. Take plot, for example, and tell me truly: am I justified in my refusal to pick up any new Christian spec-fic novel which asks, in dramatically hushed tones on its back-cover blurb, “And who is the mysterious stranger carrying the long-lost Sword of Niceness? Could he possibly be the redeemer foretold by the holy prophets of ages past?” I mean, come on. Like I don’t know the answer to that almost-rhetorical question. I’m not opposed to yet another retelling of the Christ story (there’s no escaping it, after all — not even for secular authors), just please don’t be so obvious about it. Do me the courtesy of not assuming I’ve never before encountered a Christian-themed fantasy.

And that brings me to my perennial pet-peeve: plain ol’ craft. Based on my recent sampling, I get the sense that a lot of Christian spec-fic authors really have no ambition to compose a technically beautiful novel. Perhaps it’s ’cause they want to rush the writing process (God can’t wait, after all); perhaps it’s ’cause they’ve been told one too many times that Tolkien and Lewis weren’t really men like us, but grammatical gods in human flesh, imbued with unnatural powers to conjure engaging sentence structure from the unapproachable sanctums of Oxford and Cambridge; perhaps it’s ’cause they simply don’t read enough high-quality genre literature as provided by the secular market. Whatever the cause, the result is mediocre. And this deficiency alone affronts me as a reader almost more than all other deficiencies combined. Style accounts for at least half the joy I find in reading. If the paints for a standard-issue messiah-tale get mixed on the palette of poetry before being applied by the numbers, I’ll relish the final product. But when I see a story thick with worthy themes get slopped onto the canvas in blobs of primary color, I grieve a little inside. It’s like the author didn’t have enough respect for his or her own story to tell it in a beautiful way. For myself, I can say without any sense of self-aggrandizement that I want my own writing to be not just beautiful, but gorgeous. Do I fall short of that goal? All the time. But I’ll never stop striving.

Because truth and goodness aren’t enough. We need beauty too.

My brother, also a Christian, argues it doesn’t matter whether a novel is well written or not. As long as it sells hundreds of thousands of copies for $$$$$$ the mission is accomplished.

I am working on a novel now. In my darker moments I wonder why bother crafting something good since no one will appreciate it? Why waste my time concocting ratatoille or beef burgundy when all people want is bologna sandwiches and potato chips?

Either grind out some junk writing people will wolf down indiscriminately or quit writing. My efforts to craft something beautiful and true will make people sneer at it since they read to escape not think. Why read at all? That’s what the tube is for.

Cardboard characters, contrived plots with coincidences that defy belief, pointless ACTION packed cliff hangers, and sermons in place of themes. That’s all that audiences want now. Secular and Christian.

Austin, I’m a bit confused when you say Christian writing is ‘mediocre’. I’ve been reading Christian lit for sometime now and I have yet to find one that is poorly written, unless it is possibly a self-published novel. I’m a prof writer and I will admit, I can’t and won’t write as a secular writer b/c there are plot lines I refuse to follow, lines I refuse to cross because I love Jesus more than what someone wants to read. I won’t write about sex, cursings, homosexuality, new age junk, etc. Many folks believe that b/c we won’t cross lines, our writing sucks.

I”ve also learned the more technique one learns, the better a writer they become. Writers really need to focus on Technique and what works and what doesn’t. Before the year 2000, writers mostly ignored technique, but are now discovering it works. Christian lit has gotten a lot better in the last 13 years, but it still has some ways to go. Instead of being puffed up and saying it all sucks, maybe HELP writers by encouraging them to study technique, show them what they can do with it and how it can help them. That’s what I did and still do. The writers in my writers group and growing and expanding in their writing everyday and I’m a proud mamma.

Not sure I would say that, myself. In fact, I know I wouldn’t.

Before the self-publishing and micro-press micro-revolution, e-readers, and all that, I read many rotten Christian novels. (Wouldn’t call them literature or lit.)

The first truly bad Christian novel I read was called The Third Millennium. I don’t mind saying it here, though usually I simply forget and never review the bad books I’ve read. Years ago, even as a fiction-hungry DIY teenager, I could tell this was one of the most poorly written novels ever written in any genre, much more so its own this-will-all-come-true-in-our-era end-times novel. In terms of story and even theology, it made Left Behind look like The Silmarillion.

Since then I’ve noticed the genre getting better, fans becoming savvier, authors and readers finding a basis closer to “let’s glorify God through story” rather than “let’s give the soccer moms something to distract themselves harmlessly.” But there are still bad books and hopeless tropes about. I don’t climb on them to be mean — though I do want to have a little fun with this — but because these things just don’t glorify God as well as they could. As Austin said above, that’s the goal.

Most recently I read one novel, from a mainstream Christian fiction publisher and by a semi-popular author, that included all the tropes I’d noticed over time. Finally I collected them to call them: Fiction Christians from Another Planet!.

Content is not quality. The fact that an author may choose to avoid the exploration of certain subjects says absolutely nothing whatsoever about either the craft or substance of his or her story. This lack of correlation with regard to craft is obvious: some of the most stylistically beautiful works of literature have been composed by adherents of dangerously warped worldviews, and many doctrinally-sound Christians are sadly capable of producing the most banally insipid bilge imaginable. What might be less obvious is the utter lack of correlation between content and substance. You say, for instance, that you refuse to write about “sex, cursings, homosexuality, new age junk, etc.” While there might not be anything particularly wrong with such a policy, there isn’t necessarily anything right with it, either. Goodness is ever so much more than a mere lack of badness, especially when such a lack could conceivably be due to nothing more than squeamishness or cowardice on the part of an author.

The central fallacy here is the idea that certain subjects are so intrinsically sinful that to merely discuss or portray them is to “cross a line.” But as E. Stephen pointed out above, were that the case we’d all have to avoid large swaths of the Bible itself as tawdry, lurid trash. Such an idea is, of course, ridiculous. What matters is not content per se, but how that content is handled. If all Christian authors were to avoid the subjects of “sex, cursings, homosexuality, and new age junk,” only secular authors would be left to write about such things. And, shortly thereafter, the Christian perspective on such subjects would become lost, forgotten, unknown.

Bad_cook’s guide to being an awesome Christian fiction critic:

Being mostly like an awesome secular fiction critic, because I think a fiction critic’s first concern is for the story.

If people want cut-and-dried theology, they read theology. It’s STORYTIME, snitches! Just theology won’t cut it. We need good characters, good plots, well-handled tension and conflicts, and verisimilitude. We need creativity, and I don’t just mean palette-swapping werewolf romances for Christian werewolf romances. (For real, that is a thing that exists, at least online. The ones I flipped through were pretty much as melodramatically meh as regular werewolf romances.)

I think too many try to force grit into their stories as an attempt to make them more acceptable to the secular masses (see? Christians can write gritty, too!). Then others go so far to avoid it that the work comes off as a bit milquetoast. I have no problem with self-censorship, as it is an admirable goal to reach the masses without offense. But I can understand the complaint that something is missing, and that there is little to cut one’s teeth into in much of the CBA material. I think the best stories are honest stories. That is to say, they attempt, even within a fictional framework, to tell the truth about whatever given subject matter is at hand. Even the most sanitary Amish romance can be honest, if it feels that the author is not shying away from the real complexities that make up life, love, and relationships in general. And the most gritty “realistic” novel can come off as forced and warped if it seems that the author is simply trying to shoehorn “edge” into the text in an attempt to offer “substance” (which is an altogether different thing). Perhaps the problem is that readers fail to see the distinction between content and theme (or subject matter).

At the end of the day, I’ll take an honest novel over one that tries too hard to offend, or strains not to. Honesty in writing covers a multitude of authorial sins.

I enjoyed one of the first Amish books called The Shunning. It dealt with real, complex themes like the constrictive lifestyles many church goers are forced into by small minded legalists running the show. But when it went into the formulaic adoptive child looks for lost “real mommy”, narrowly missing True Love who had been supposedly drowned at sea I sighed. I gave the book to my aunt who reads all things sentimental, and swore not to bother with the sequels.

The whole highbrow/lowbrow thing tends to extend to mainstream/genre in writing classes far too often. One of my textbooks actually said:

Many–perhaps most–teachers of fiction writing do not accept manuscripts in genre, and I believe there’s good reason for this, which is that wereas writing litary fiction can teach you how to write good genre fiction, writing genre fiction does not teach you to write good liteary fiction–does not, in effect, teach you “how to write,” by which I mean how to be original and meaningful in words.–

That’s its own post, but I think genre, especially speculative, defaults to “lowbrow” in people’s minds.

Speculative fiction can actually cross over to literary rather easily if well written. I find Christian spec fiction is often better than the secular kind since it forces an outside the suburbia box view of the universe while maintaining Christian standards and can be far less preachy than stuff like The Handmaiden’s Tale.

This openness helps the writer use imagination to create better characters, and use altered reality as an allegory for truths about God and the human condition. Like Kafka’s stories. He was an atheist, but he dared to ask questions many writers today are afraid to. And he asked the right questions; sadly he never found the Answer.

Mr Burnett, you are my hero!!!! I love this article. I don’t understand those who say Christian liturature just SUCCCKKKS!!!! In all due honesty, I never thought it ‘sucked’, just not as nasty as secular books. As for fantasy? Has anyone here lately READ a secular fantasy novel? I went to the library last year and all I saw were book after book of heros who had sex with anyone with genitalia and who were the offspring of some god and a desperate human woman. Ick!! And they say christian lit is bad. I looovvve Christian fantasy and have my own favey writers now. Also one thing that I’ve kinda noticed are the folks who claim christian lit sucks are those who’ve never written a novel or some, not all, are self-published and pretty much think they know how the publishing world works. Gesh!!!

Wow… I tried to post a rebuttal to this blanket accusation all day, but my comment never gets through. Since I got a different comment half-through last night (in reply to E. Stephen Burnett above), it got truncated, I’ll try again, this time only saying that I have read secular-published fantasy, even recently, and they’re not all like that. 🙁

My favorite modern Christian writers are all indie novelists. For a while the CBA was too scared to do anything new. That’s part of the reason assembly line formula driven novels abounded in the 90’s. Indie publishing is great for small niches like this.

I’ve been thinking about this subject since this article and discussion went live. I agree that Christian fiction is not inherently worse than secular/mainstream fiction. However, it is also a fact that I have felt disappointed with much of the Christian speculative fiction that I have read. My feeling of disappointment is personal and subject, and also does not indicate total dislike or unappreciation of the works. There are things that are done well in all the Christian speculative novels that I’ve read.

Alone, my personal disappointment is meaningless. But if lots of readers who have sincerely tried Christian speculative fiction have similar feelings, then I think that does indicate a problem, or at least a deficiency. Whether or not that deficiency can be corrected is a good question. It may simply be a matter of this being a relatively small community of writers, most of whom are relatively new at their craft.

Austin Gunderson wrote:

I suspect that Austin is on to something here. I don’t know this community well enough to say how much this applies, but I think it is probably true that we aren’t very good at rigorous, internal criticism. Again, this may be a nearly inevitable result of the smallness of the CSF community. We want to feel like a happy family, doubly so because of our faith. But real families are not sweet and affectionate all the time.

I wish I hadn’t posted this comment last night. It was a bad decision.

Because you don’t really believe something that you said, or because you think you could’ve phrased it better?

Neither. I’m just feeling embarrassed.

I want to find a series like The Wheel of Time, a saga that awes me in its depth of meaning and sense of honor. I don’t look for perfection on any level, neither mechanical nor literary perfection. The Wheel of Time is so far from perfect that I don’t think using it as my personal standard is unreasonable or elitist. I just like it.

Every time I read a Christian speculative novel and I don’t get the experience I’m searching for, I can’t help but wonder whether I might have had a better chance to get a good book from the shelf at the library for free. (“Good book” meaning subjectively one I like.) That feeling is probably unfounded. I don’t know for sure that many of the secular high fantasy books in the section at the library have what I’m looking for, and I do know that secular fantasy has its share of stinkers too. But that doesn’t change the feeling.

So, yeah, I just embarrassed myself again. 😉

You’ve nothing to be embarrassed about. It’s not as though it’s your duty to appreciate Christian spec-fiction just ’cause it’s written by Christians. Such an approach would suck all joy and meaning from the whole pursuit.

My prescription: read Lewis’ Space Trilogy and Peretti’s This Present Darkness to remind yourself that truly great Christian spec-fiction isn’t a pipe-dream, and then read Sanderson’s The Way of Kings to renew your imagination with the finest work of contemporary epic fantasy, period. It’s colossal in scope, rich in complexity, deep in profundity, breathless in tension, and beautiful in execution. It will move you and raise your personal standards for all other authors, which will be a good thing.

I thought about this a little more, and I think the whole problem comes down to the fact that the Christian speculative fiction community doesn’t have hundreds of readers who aren’t also trying to get published. That’s why the books on the library’s shelf have a relatively high chance of being subjectively interesting. Even though subjective interest is subjective, the collective masses of fantasy fans have narrowed the set of all available fantasy novels to those that have some kind of broad appeal. My personal tastes are my own, but among the collective masses of fantasy fans, there are probably enough people who share my approximate tastes that the library offers something for us. This is less true of a bookstore, which sells all the latest trash. The library collects books that many people seem to think are worth reading.

I do appreciate at least most of the CSF novels I’ve read so far. By ‘appreciate,’ I mean that I can enjoy them for what they are, even if they weren’t quite what I was looking for. I think I may have some obligation to enjoy that which I consume, at least to try to, although this duty is not exclusive to Christians’ works. You’re right, though; I don’t have any duty to rank Christians’ novels as my favorites.

Thanks for the recommendations! I’ve read Space Trilogy, and it is the best of all Lewis’s fiction, simultaneously philosophical, literary, and pleasantly campy in it’s science fiction tropes. I haven’t read This Present Darkness, even though I’ve known for years that I should. Just finished The Well of Ascension, so I have to grab The Hero of Ages before starting The Way of Kings. I’m looking forward to it. 🙂

Don’t forget Charles Williams’ novels. Early urban fantasy without the love triangles. He was buddies with Lewis and Tolkien, a fellow Inkling.

On Moral Fiction by John Gardner is a must for Christian writers. His novel Grendel is also good.

For those wondering about this topic’s converse, I recently realized I’ll need to write a companion piece: How to Be a Silly Christian Fiction Defender.

A time and a place for everything. You can tell from my comments which side I err on.

[…] Susan on How to Be a Silly Christian Fiction Critic […]

[…] of the critics (myself included) tend to oversimplify the problems with the market. Thankfully, E. Stephen Burnett of Speculative Faith provides a helpful critique of such […]

Austin G., you are the most clear-headed thinker I’ve encountered in a good while. Thank you.

Agreed. Austin and I share a dislike for poorly written, shallow-theme Christian novels and the evangelical subculture as a whole.

Yet I also want to recognize that a) no part of culture is utterly devoid of redeeming qualities; b) many people stereotype the “Christian fiction” industry because of the — still-unrebutted? — reasons sardonically listed above.

Sardonic, am I? I was aiming for acerbic. ;-p

And I just want to reiterate the fact that I chide the genre out of love. Christian spec fiction has incredible potential for greatness. There are those who claim it’s a genre limited in depth or reach by its very nature — that expectations for improvement are unrealistic at best — but I’m not one of them. In no way do I believe that fans of Christian spec fiction should resign themselves to subpar storytelling. And I’ll keep beating this drum until I read something written by a Christian that’s comparable to the best works currently produced by secular genre authorship.

Very good, Andun, and I agree on all levels. It /can/ be done, it /should/ be done, but it generally (and sadly) isn’t being done.

“And I’ll keep beating this drum until I read something written by a Christian that’s comparable to the best works currently produced by secular genre authorship.” I do believe you’ve been inside my head …

[…] How to Be a Silly Christian Fiction Critic […]