95 Theses for Christian Fiction Reformation, part 4

This Tuesday, Oct. 31, marks a holiday that strikes fear into the hearts of some Christians and has proved controversial for now exactly 500 years: Reformation Day.

On that Oct. 31, 1517, monk Martin Luther stuck his 95 theses to the church door at Wittenberg—that is, 95 ways the Catholic church was teaching wrongly.1 Ever since, Christians who later became known by the term protestants (originally a legal term) have celebrated the Reformation and its emphasis on five solas:

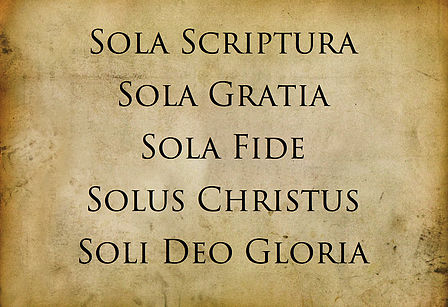

Sola Scriptura (“Scripture alone”): The Bible alone is our highest authority.

Sola Fide (“faith alone”): We are saved through faith alone in Jesus Christ.

Sola Gratia (“grace alone”): We are saved by the grace of God alone.

Solus Christus (“Christ alone”): Jesus Christ alone is our Lord, Savior, and King.

Soli Deo Gloria (“to the glory of God alone”): We live for the glory of God alone.2

Of course, Christian fans of fantasy (or speculative) stories should want to embrace these five solas in their own nonfiction lives. But each statement can apply specifically to any other reformation-style project. This includes the reformation of Christian-made fiction that I’ve been arguing in this series, 95 Theses for Christian Fiction Reformation:

- The purpose of Christian-made stories,

- What’s wrong with Christian-made stories,

- What’s right with Christian-made stories,

- How Christian readers can reform these stories in the future.

We’ll now conclude with the final 20 theses, which apply not to the makers of these stories but first to the readers of these stories (to whom the makers can only respond).

Part 4: How Christians can reform Christian-made stories.

- Christians must embrace sola Scriptura as a nonfiction principle that no Christian-made fictional work can contradict, in theme or in style. (This does not mean the work is full of verses or doctrine affirmations. It only means the work does not contradict)

- Christian stories must embrace sola fide—faith alone—as the basis for any character’s salvation or state of faith. (We conclude this also applies to fantasy-world salvations.)

- Christian stories ought not imply that any morality, culture, or action contradicts sola gratia, or salvation through grace alone. This is vital, in a Church and a world that are constantly tempted to presume our salvation or growth in holiness depends on us.

- Christian stories must exalt Solus Christus, Jesus Christ, by name, fantasy-world symbol or supposal, or simply by portraying His truth, beauty, and goodness with excellence.

- We must enjoy Christian stories soli Deo gloria, for the glory of God alone. This means we fight to enjoy them when they’re not so great, and delight in enjoying them when clearly the stories’ creators have striven to honor the Creator in styles and themes. In any case, we laugh and/or repent for our failings, and thank God for our successes.

- We must maintain a high and biblical view of the capital-C church (all of Jesus’s people, wherever they are), and the lowercase-C local church we call home. In other words, we cannot skip over our churches’ key role in the world, including our creative works.

- When Christian stories (or their authors) seem to clash with these solas, we must be careful to discern minor faults from major ones. We must also be careful to avoid acting like the author’s or publisher’s local church—e.g. the only institution Jesus has set up to help anyone grow in a faith community that offers membership and belief standards.

- We need to celebrate publicly the Christian-made stories we love, even if our family or have ever heard or cared for these stories. (If nothing else, this kind of public sharing is great practice for sharing Jesus himself—who’s also often maligned—with others!)

- This means we don’t feel silly about our “fandom” for these stories. We don’t hide this “light” under a bushel basket. We don’t partition our “Christian” and “normal” lives. This also means starting or joining a Christian fiction book club. (For example, the book clubs we are starting next year as part of the Lorehaven initiative and magazine.)

- Especially for fans of Christian fantasy: we need to follow the apostle Paul’s commands about things we celebrate or happily consume. We need to “be fully convinced” in our own minds about these stories’ positive benefits, and not “let what you regard as good be spoken of as evil” (Romans 14: 5, 16).3

- For fans of any fiction genre, but especially Christian-made fantasy: we need to recover some expectations shaped by classical fiction literature. We don’t mean that every book ought to be like Dickens. But at back of our minds, we ought to have read many old novels, so our preferences and hearts as readers are better trained to expect more.4

- What about the continued presence of bad Christian fiction, some of which is marketed with nonfiction labels? Let’s graciously yet firmly critique it based solely on Scripture. But let’s mainly decrease the natural market for it, simply by living and becoming the next generation that declines to enable this kind of soft-soap “inspirational” religion.

- However, let’s avoid a kind of iconoclasm, or smashing to bits the things we view as sinful relics of badly made Christian fiction. This means that if existing Christian fiction infrastructures fail (bookstores, publishers, and so on), we don’t celebrate.

- We also avoid any kind of scorched-earth policy in our thinking, our rhetoric, and especially the ways we treat Christians who support or defend poorly made fiction for shallow reasons (e.g., it’s “inspirational” or “clean”). After all, Jesus doesn’t nuke people and things He loves from orbit and start over. He redeems and even reforms His creations.

- To that end, let’s reform some specific Christian-made creative concepts that were just executed badly before. For example, Christian t-shirts. We’ve all seen bad ones. But this one is a great one, and we need to create and wear (non-ironically) designs like this one.

- Let’s critique and gradually withdraw market support for Christian novels that obscure the Gospel even while attempting pseudo-“evangelism” on readers who will never actually read the book. But let’s preserve the heart of this goal of much Christian fiction: to share Jesus with the reader. We do need “explicit content” Christian works!

- Push the frontiers. We can find freedom, not restriction, by going deeper into explicitly biblical views and overtly Christian content. In turn, we’ll grow to expect bigger themes, complex characters, and a robust vision of excellence for the stories we want to see.

- Above all, keep an eternal perspective. This series began by opposing the notion that Christian-made creative works are little more than trivial “containers” for the real prize inside (e.g. truth or morals). Such a notion denies the biblical teaching that God created humans to glorify Him through our exploration of Earth and our creative acts (Genesis 1:26-28). In all likelihood, we will spend eternity worshiping God by acting as humans ought to act—enjoying and making stories and other creative works to reflect Him.5

- Remember that for the present, our abilities are limited by sin and our groaning creation (Romans 8). But we have biblical cause to expect that even our sin-marred attempts at glorifying God today will have eternal rewards. Both our overtly “spiritual” acts, and our delight in creative works, can help point ourselves and other people toward our Creator.

- Finally, we recall that it’s His sake alone that we ever try to “reform” anything, whether it’s the faith altogether or the fiction made by our brothers and sisters in the faith.

- Historian Andrew Pettegree says, “The nail idea (about Martin Luther) is a romantic invention of the nineteenth century. I’m taking quite a middle way saying he glued it.” At least we can keep the church door. ↩

- The Five Solas – Points from the Past that Should Matter to You, Justin Holcomb, Christianity.com. ↩

- This means that, if needed, we will research why God gifted humans with the ability to enjoy and make creative fiction. This also means that, if needed, we’re willing to answer criticisms from other Christians. ↩

- This is how fantasy’s “patron saints,” J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, could do what they did. We’ll never see even modern-day equivalent works among newer Christian novels without at least having a little of their kind of classical, history-based education. ↩

- Consider the biblical and logical basis for the idea that human popular culture will (in some form) last forever at Yes, New Earth Will Have Movies!, E. Stephen Burnett at Christ and Pop Culture. ↩

Share your fantastical thoughts.