What Makes Fantasy Work? Part 1

More and more fantasy, even Christian fantasy, is available these days. Some small presses are devoted to the genre and its cousins, science fiction and horror. But some authors are putting their work on their sites for free, some are self-publishing, and traditional publishers are adding more and more titles to their stock.

More and more fantasy, even Christian fantasy, is available these days. Some small presses are devoted to the genre and its cousins, science fiction and horror. But some authors are putting their work on their sites for free, some are self-publishing, and traditional publishers are adding more and more titles to their stock.

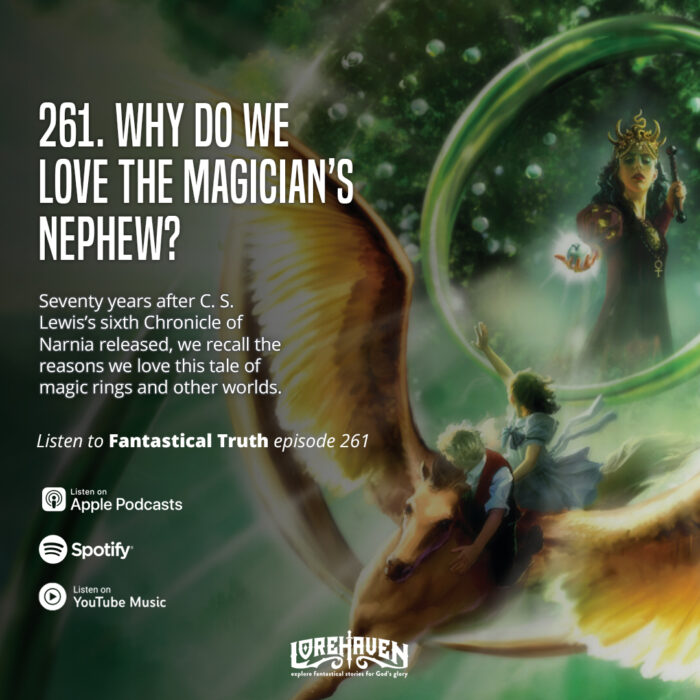

The truth is, however, most readers will only learn of a small number of the books that are available. Chalk it up to promotion or platform, if you will, but I don’t think we can ignore that some fantasy works better than most. Readers love Narnia and Lord of the Rings, and they love a handful of later fantasies. But a lot of stories don’t go viral, don’t get hundreds of reviews, and in fact get tepid responses. So what makes fantasy work?

In some ways, I think the answer is no different than what makes any other piece of fiction work. But I also think fantasy aims to accomplish more, so it has more that can go wrong.

I suppose that isn’t quite true. Mystery writers could say that mystery tries to accomplish more because the story tries to create a puzzle that keeps the reader guessing. And romance writers could say that romance tries to accomplish more because the story tries to bring two people together while keeping them apart. Writers of historical fiction could really make a case for their fiction doing more.

In other words, each genre has its own tropes to which the author must adhere, so it isn’t quite as simple as just writing a story. But when I say that fantasy does more, I’m thinking of the depth—the way that the story is only the obvious part of what the writer is saying, not the entire substance.

In C. S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces, for example, Orual’s experiences say much more about Mankind’s spiritual life than about the mistakes of one lonely girl who became queen.

In C. S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces, for example, Orual’s experiences say much more about Mankind’s spiritual life than about the mistakes of one lonely girl who became queen.

But what makes Lewis’s stories work so well? Why, in fact, are the Narnia stories known around the world but few people have read Till We Have Faces? Of course, the only people I know who have read the latter, count it among their favorites, so I’m not suggesting it doesn’t “work.”

And yet, it’s hard to say it works as well as Narnia. Otherwise, wouldn’t there be as many people who have read it and loved it? I suppose we could argue that children’s books have an advantage. Often times, parents who love the books they enjoyed as children, read them aloud to their children, and the love of the books is passed on, as much by the pleasure of the reading aloud experience as by the quality of the stories.

Has anyone read Till We Have Faces aloud to their children lately? I suspect not. It’s not that kind of book.

So I suppose the first thing to realize is that what “works” is somewhat subjective. Yet I can’t help thinking that a lot of the books available today don’t work, or at least not as well.

Perhaps the key is to look at what each book is trying to accomplish. The question would then be, did the author get it done?

The higher the book aims, the harder it is to reach that goal. Consequently, if a story aims to be a sweet romance as a means of providing a little escape for the reader, then it works if it does just that. But if it aims to be the next Gone with the Wind, the author has set an ambitious goal and her work must be judged based on whether or not she accomplished what she set out to do. If she wrote a sweet romance, albeit a thousand pages long, I’d say she did not meet her goal.

So too with fantasy.

When I first considered the question, what makes fantasy work, my immediate thought was, an engaging character. That’s when I realized that there might not be so much difference between fantasy and other fiction.

In some of the fantasy that doesn’t seem to be working, I’ve seen three problems with the central character—she/he doesn’t have a specific goal, is nondescript, or whines.

Readers are most engaged with a character if they care about him and if they can cheer him along as he tries to accomplish an important goal. He needs to seem real, so he must have a rounded personality. For fallen humanity, that means weaknesses and needs as well as strengths and things to offer others. At times, however, a character weakness can be painted with too much emphasis. I know because I created such a character.

It crushed me at first when members of my critique group told me they hated my main character. Hated him? I loved him. How could they misunderstand him so completely? Yes, he had problems, but don’t all characters? I mean, isn’t that part of the character arc?

That, in a nutshell, is the balancing act authors must achieve—give the character problems but not let him become embittered, sullen, whiny, complaining, slothful.

In some ways, Jonathan Rogers’ Grady in The Charlatan’s Boy is the perfect character. He’s got a problem—he’s an orphan, but that’s not all of it. The only person who knows anything about where he came from is unreliable—worse than unreliable. He twists the truth at will, however it suits him.

But instead of wallowing in self-pity, Grady makes the most of his circumstances. Here’s where the reader sees his real strengths. He’s loyal, hard working, and humble enough to do the job he needs to do.

So the first thing fantasy has to have in order to work is a main character that is believable and engaging.

The second thing, because this is fantasy I’m talking about, is a well-developed, consistent world. This is the aspect J. K. Rowling mastered. If I were to grade her, I might give her a C or C+ for her character. Harry wasn’t particularly believable in the first book because the abuse he suffered at the hands of the Dursleys was over the top. Nor was he particularly engaging. He didn’t whine but neither did he do anything to change his situation.

The second thing, because this is fantasy I’m talking about, is a well-developed, consistent world. This is the aspect J. K. Rowling mastered. If I were to grade her, I might give her a C or C+ for her character. Harry wasn’t particularly believable in the first book because the abuse he suffered at the hands of the Dursleys was over the top. Nor was he particularly engaging. He didn’t whine but neither did he do anything to change his situation.

But the world Rowling created was awesome. She did such a great job creating a magic place that the story came alive. She paid attention to detail and didn’t overlook anything.

In Hogwarts, food appeared magically on plates, the ceiling in the dining hall changed to appear like the outdoor sky, persons in portraits moved (and moved from their own frame to another’s), persons in newspaper photos moved too, and so did the figures on the cards that came with certain candy. And those chocolate frogs could actually jump away. The students had to be taught how to fly a boom and how to use their wands. And on and on and on. So many little details, everyday things twisted to fit a place where magic was real.

But there’s still more to this “What makes fantasy work” question which I’ll look at next time.

Adapted from posts on this subject at A Christian Worldview of Fiction

And by contrast, the best fantasy heroes who do work are those who:

I believe the greatest virtue a character can “perform” for readers is the virtue of surprise. Potentially great stories have been forgotten, or should be forgotten, because they include no genuine surprises whatsoever. Whereas any justifiably popular story that has gained its position because of praiseworthy characters, plot, creativity, anything else — all of those can be traced to the virtue of true surprise.

Recently I have abandoned one book about 30 percent through and picked up another chiefly because one set of characters — with the author behind them, of course — actually did surprise me. That helps earn my trust, and my readership.

And it also means, to my surprise, I’ll likely forgive pretty much any other author sin, be it cheesy dialogue, head-hopping, slow spots, or even (gasp!) preachiness.

I totally agree, though I have misgivings about Rowlings’ worldbuilding. The trappings are wonderful–the fake Latin, the nifty little spells, but my problem is the underlying worldbuilding doesn’t work. What is all that magic learning for? It certainly doesn’t fix any problems or make life better, for all its power–doesn’t cure cancer, keep babies from dying of SIDS, resolve the problems in Africa, etc. It seems entirely bent on training mages to fight each other, once they grow up and decide which “side” they are on (though a lot of that is determined by the sorting hat.)

However, a nine year old reader doesn’t care. She’s reading for the fun, and she doesn’t notice that all the characters are one dimensional, that nobody ever really changes. Rowling was good with visuals, not with depth–no wonder the books translated so splendidly to movies.

The world works, I would suggest, because it’s a version of the mythology concept of faerie as a place. Rowling combined “ordinary” life, or that kind of life a few centuries ago, with the concept that some people in modern times are still born with fairy-like “wizarding” abilities. In that setting, they wouldn’t do much more than live ordinary lives, work, raise their families, and not have huge quests or life-changing events.

… With the exception, of course, of when a bad Dark wizard goes beyond very bad.

Character is hard to criticize, maybe more so in fantasy than in other genres. Some people say that all Robert Jordan’s characters in The Wheel of Time are the same pale stereotypes, while others uphold his writing as an example of strongly character driven fantasy.

For my part, I somewhat disagree that the greatest strength of Harry Potter is the world. I’ve read six of the seven books so far, and I think the series is strongly driven by constantly developing characters. In fact, the characters are shaped by their relationship with the fantastic. Were their ancestors part of this mysterious fantastic reality for many generations, or were they normal people born to normal parents who turned out to be of the fantastic nonetheless? How do they respond to their fantastic environment at Hogwarts? In contrast, I’m not very impressed with the setting of Harry Potter, because I prefer harder fantasy with stronger mythological elements and deeper meaning and coherence behind the magic.

Interesting thought–that the characters are shaped by their relationship to the fantastic. That certainly plays out in the live of both Harry and Tom Riddle as well as in the lives of the muggle-born Hermiony and the true bloods–Ron and Draco.

But I still think all the magic incorporated with the familiar made the Harry Potter books what they are.

Becky

I definitely think the characters are one of the most important elements. Mostly in fanfiction, but even in original works, it’s really common have characters reduced to stereotypes who just fill stock roles. Another important aspect of character is consistency.

I’ve been watching ABC’s Once Upon a Time, and the characters bug me a lot with inconsistent writing and behavior. The other thing that is driving me crazy is the glossing over of the Evil Queen’s behavior–they give her way to much credit when she tries to “change,”

I had the same problem with my previous draft–beta readers came back saying my hero was unlikeable. Thankfully, they also pointed to certain things the hero did, and I was able to fix them. He’s much more likeable now, I think.

But then my other hero, in book 2, came in and took the stage by storm. He drives the story with his decisions and actions (for good or bad, although his decisions get worse as the stakes get higher–he doesn’t handle stress well).

Lately I’ve stopped reading a couple of books in a row because I didn’t care about the characters. My personal yardstick is, “Does this character make me laugh?” If they’re witty or clever in any way, then I know the author can also make me slide the other way and yank my heartstrings. (Rebecca Minor’s next book is awesome. Just sayin’.)

I’m chewing through Daughter of Smoke and Bone right now (all about completely non-Christian demons and angels and their perpetual war–and Prague), and it’s wonderful. But what makes it wonderful are the characters. They’re funny, they’re sad, they’re intriguing as heck.

Kessie, I like that yardstick of “does this character make me laugh?” As a high-and-mighty teenager, I was intent on making every character incredibly weak and flawed, so as to avoid the label “Mary Sue.” In the process, I ended up creating a lot of “reverse Mary Sues” who were ridiculously unlikeable or else had their heads stick up their own butts in misery so much that no one would possibly like being around them, except perhaps my angsty, teenaged self.

Now I strive for that “humor measure” and I know I’ve hit it when beta readers both laugh at a scene, and then a few paragraphs later are deeply empathizing (or even yelling at) my character. And then want more, right away.

Would you recommend Daughter of Smoke and Bone? The title and cover art are so pretty that I’ve been tempted to grab it up, but I’ve been burned by so many YA titles with pretty covers.

One thing I would add to the list is conciseness. I think this is the hardest to manage, because speculative fiction by its very nature lends to long-windedness. And I love a good world-building epic as much as the next person–I read real world cultural profiles for the fun of it. However, no matter how awesome the world, if the characters or plot are lackluster or annoying, then I’ll end up dropping the book, or else paging through for the description parts, and then dropping the book. World building and description must serve character and story. Otherwise, it’s just really awesome window dressing.

Their heads stuck up their own butts in misery, LOL! I’ve written a few of those!

I’m only halfway through Smoke and Bone, and I’m enjoying it a lot so far. It’s fantasy angels and fantasy demons (chimerae), and there’s other worlds. Aside from Diana Wynne Jones, I don’t see a lot of authors taking our modern-day world, with airplanes and guns, and sticking in parallel worlds.

(BTW, I recommend Diana Wynne Jones for great characters and compelling plots. She wrote Howl’s Moving Castle, for example. But my favorite books of hers are the Chrestomanci books, starting with the Lives of Christopher Chant, and the Merlin Conspiracy. She makes J.K. Rowling look like a hack.)

Thank goodness for beta readers and crit partners! I reworked my protag, too, and think I’ve made him someone readers care about. But I learned how hard it is, what a balancing act it is, to present a flawed person in a way that readers don’t despise him for his flaws.

I think arrogance might be the hardest trait to deal with. An arrogant character, like an arrogant person, isn’t fun to be around. But does that mean we can never tackle the problem of arrogance in a novel?

Balance, I think.

Becky

One element of good fantasy, that is alternately overlooked or scorned, is simplicity. A good story, one that we carry with us long after we’ve put the book down, is something that we can easily grasp. I’m not saying that fantasy is one-dimensional or that details aren’t important. Neither is true. But good fiction is in the “bones” of the story, not the details of freckle patterns or clothing choices. When a story is built with weak bones, poor joints, or a bad heart, no amount of pretty details will successfully hide the internal problems.

When a story starts with something simple, the reader is free to emotionally engage. This creates empathy between the reader and the character (NOT between the reader and the writer), so the reader is willing to follow into the wardrobe, into the woods, into the night. The details of Narnia or Hogwarts or the Shire may be rich and well-conceived, but they are just details. But the readers of Harry Potter want to know more because Harry’s never seen this magical side of the world before and is soaking up these details. The reader easily believes Harry is learning, and learns alongside him. When the Pevensies are deposited with Professor Kirk, the reader can easily believe that some restless, worried children might identify with a world suppressed by a horrible dictator who had kept Christmas away for a hundred years. We are lured in more by simple, evocative bones of a story than details like the color of Lucy’s scarf or what Harry eats for breakfast. Those details make us believe we are in the story, but they don’t draw us further up and in.

But I do think that the need for good “bones” in a story is more transparent in fantasy, which is why it receives the most criticism. A lot of readers (and critiquers) seem to think that complexity is the mark of well-thought-out adult fiction. Nyeh. Not so much, especially in fantasy. The more a character, situation, or world must be explained, the less likely the reader is to believe it, much less get drawn in. The author comes more to the fore, and the characters of the story become secondary. Which leads to a mediocre story. Artificial limbs don’t look as natural as real ones, and when the reader becomes aware that the bones of the story are partly shored up by inorganic parts, most readers pull away a bit. And without that empathy, that shared connection between reader and character, the story looks much flatter.

Great observations, Lex. One of the things I particularly noticed as I reread the Harry Potter books was how Ms. Rowling used the details as part of the bones of her story. So in book one finding the characters in portraits can talk and move and even change frames becomes key to the blot in books 5 and 6 and 7. Same with the owls and port keys and so many other specifics of the world. Initially they might look like window dressing, but a capable writer will know how to put those details to use.

Becky