Theophanies and Suffering in Christian Fantasy

I have a confession to make. I’m always a little scared to portray God in my books. I mean, I do it anyway, but it’s frightening. I tend to feel a “prickle” on the back of my neck especially when I’m writing a fictional dialogue for God in any of his three persons (so cheeky). Careful, the voice in my head says, He’s watching, and what you “make” Him say matters. Mess it up and ZAP! After all, one does not just misrepresent God and get away with it. And yet, showing the character of God through writing is necessary. So, he is active and personal in my books—portrayed through no metaphor or abstract concept—showing up in all three persons of the Trinity. This poses a problem, however. How can there be a sense of urgency or danger when the omnipotent God of the universe (and beyond) is a main character in a story? And why, for that matter, would an omnipotent God allow his heroes to suffer when he could easily fix their dilemmas? Here we stumble on the reason it’s worth the risk to show God to the world through fantasy. Those questions are the same many level at God.

I have a confession to make. I’m always a little scared to portray God in my books. I mean, I do it anyway, but it’s frightening. I tend to feel a “prickle” on the back of my neck especially when I’m writing a fictional dialogue for God in any of his three persons (so cheeky). Careful, the voice in my head says, He’s watching, and what you “make” Him say matters. Mess it up and ZAP! After all, one does not just misrepresent God and get away with it. And yet, showing the character of God through writing is necessary. So, he is active and personal in my books—portrayed through no metaphor or abstract concept—showing up in all three persons of the Trinity. This poses a problem, however. How can there be a sense of urgency or danger when the omnipotent God of the universe (and beyond) is a main character in a story? And why, for that matter, would an omnipotent God allow his heroes to suffer when he could easily fix their dilemmas? Here we stumble on the reason it’s worth the risk to show God to the world through fantasy. Those questions are the same many level at God.

How can a loving, omnipotent God allow good people to suffer?

It’s been a mainstay of skeptics since—well, shoot—since the beginning of time. Forget the skeptics; it’s been a weapon of the Enemy’s since the beginning. One could even interpret Satan’s question, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat of any tree in the garden’?” as “If God was loving and good, would he really keep you from that? A loving God wouldn’t keep you from enlightenment, would he?”

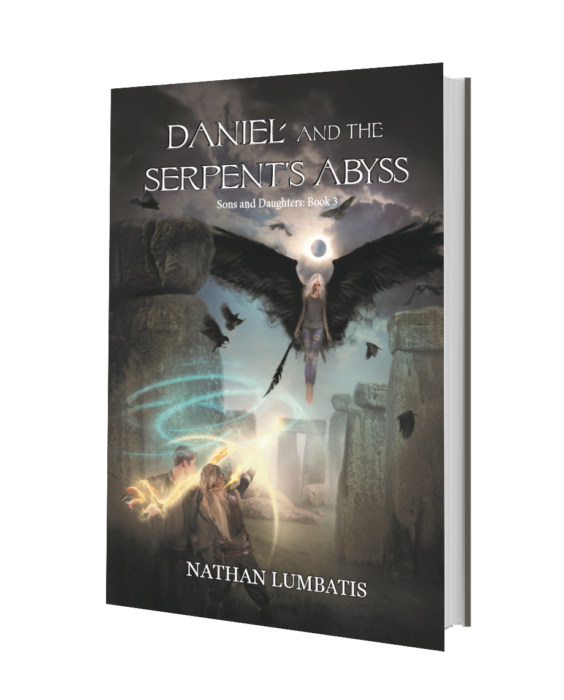

In the third book in my series, Daniel and the Serpent’s Abyss (buy a dozen copies on Amazon please) this topic is explored through the story of Raylin. Raylin is a supporting character who is currently under the possessing power of her sword: the Voidblade. It’s a black, ugly weapon with the ability to suck in the souls of vanquished foes and grant its wielder their power. She is warned from the start of the series that the dark spirits within the blade will eventually possess her. Her desire for revenge against the Enemy is so strong, however, that she can resist its influence, and that its power will be enough—no matter the Voidblade was created by him in the first place.

So, we see a predictable dilemma: a human making destructive choices out of ignorance, anger, and revenge because she doesn’t want to heed God’s warning. The result? Bondage, despair, insanity, and utter dependence upon God to provide salvation. Then, he swoops in and undoes all her bad choices and their consequences, right? Not quite. At this juncture in the series, the only way for Raylin to be truly saved is for Daniel and his friends to somehow get Raylin to the bottom of the Serpent’s Abyss, where they can use the Abyssal Staff to permanently free her from the power of the spirits possessing her. Even that won’t work, though, unless she willingly relinquishes the Voidblade and repents of her sin. Oh, did I mention the Abyss is where Satan (in his true form) dwells? It’s a harrowing and painful experience, but necessary. Why? A quick internet search for verses on repentance gives us one of the answers. Repentance brings freedom from sin, and repentance is something we must choose. Whether God has manifested himself in blazing glory (á la Paul), a sermon, or that still, small voice in our minds, he calls us to repentance and waits for our reply rather than bulldozing over us. Ezekiel and Peter are helpful.

Ezekiel 18:30-32 ESV

“Therefore I will judge … every one according to his ways, declares the Lord GOD. Repent and turn from all your transgressions, lest iniquity be your ruin. Cast away from you all the transgressions …. For I have no pleasure in the death of anyone … so turn, and live.”

2 Peter 3:9 ESV

The Lord … is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance.

All of this is to say, when I portray God as omnipotent, omniscient, and terrifying-but-loving, he must also be portrayed as working salvation by patiently allowing his children to bumble their way through mistakes, pain, and ruin to (hopefully) find freedom through repentance. He is not a tyrant of hearts and wills.

All of this is to say, when I portray God as omnipotent, omniscient, and terrifying-but-loving, he must also be portrayed as working salvation by patiently allowing his children to bumble their way through mistakes, pain, and ruin to (hopefully) find freedom through repentance. He is not a tyrant of hearts and wills.

To illustrate this, here is an excerpt from Daniel and the Serpent’s Abyss. The Triune God has arrived in the Abyss at the moment of Raylin’s opportunity to repent. I’ve shortened it from how it appears in the book for brevity sake, but I hope it will still exemplify the point of this article.

“What do you want with me?” the Serpent and his incarnations demanded in one unified, whining voice. “Have you come to torment me before my time? Will the Father also descend from his Mountain to cast me into the Lake of Fire?” All the Enemy’s forms took one enormous breath. “It is not my TIME! What do you want with me?” they screamed again.

The Son raised his hand, and the Enemy fell silent, except for the constant scraping and scratching noise of his myriad scales, claws, and horns rasping against the ground.

He turned to Raylin. “I am Alpha and Omega. First and Last. Beginning …” he paused, and at that moment, the veil between them and reality drew apart. The Father’s Mountain appeared behind the Son. “… and End,” the Father said in his cosmically deep voice.

The Abyss shook violently.Raylin lifted her eyes and stared up at the Mountain. “I don’t understand.” Her voice was flat and confused. “He fears you. He bows.” She limply gestured toward the Enemy, shaking her head. “Why don’t you destroy him now? If your power is this great, why did you let me suffer? Why didn’t you rescue me?” Tears streamed down Raylin’s face, and her voice fell to a shaky whimper. “I was scared.”

Daniel didn’t have to guess at Raylin’s meaning. He knew she now spoke out of her childhood trauma—the terror of being sold as a slave and exposed to atrocities he could only imagine. Even with never knowing his biological parents, Daniel had never experienced even half of what she went through. He let his eyes drift to his biological mother, then to his mom and dad, all still praying fervently for his protection. If he had ever thought his life hard, one glance at Raylin’s blew that notion right out of the water. He’d been sheltered and protected. She’d been exposed to the worst of reality.

“Some are called to suffer, Raylin,” the Son said, still standing at the base of the Mountain. “Among the Three, mine was a path of sorrow.”

Images flashed through all their minds. A life of ridicule and poverty. Foreknowledge of an inescapable, painful death. The Enemy in various guises, haunting every step like a nagging ghost, kindling every demeaning comment. Unjust accusation. Torture. A Roman cross soaked in blood. Descent into the darkness of death and hell. And, worst of all: separation from the Father.

But then …

Light. Life. Inheritance. Redemption of countless people—a vast sea of children pulled out of darkness and into a world of light, an innumerable host of men and women flooding the plains of Heaven. All because of the suffering, death, and resurrection of the Son. In one burst of understanding, Daniel saw the terrible things experienced by the Son as unworthy of comparison with his great work of redemption.

“Your suffering was not purposeless, either. Nor will it be in vain. Through it, you will find compassion for others who suffer, and you have won immense strength. Repent of your anger, Raylin. Sin no more. Come to me and find rest.”

When we read or write stories of the omnipotent God, fantastical or otherwise, remember that his character is not impugned by the suffering brought on by the Enemy’s will and our sin. His omnipotence and goodness do not require him to filter out all the consequences of sin in the world, as much as we wish they did. As the Son explains to Raylin, because of that physical and spiritual suffering we become aware that we are on the path to eternal destruction. As the child knows the pain of her stove-burned hand means she must pull it back or else lose it to fire, so too we (and the characters in our stories) rightly interpret our trials and suffering as evidence of our need to run to a redeeming God. I will, foolishly or bravely (you decide), continue to write stories where God shows up unapologetically omnipotent, and yet allow his creatures to struggle. It’s my hope that, by doing so, readers will have a clearer perspective on the meaning of their own trials, and the deceptive attacks of the Enemy will fall on deaf ears.

A wonderful article, Nathan! This is the type of content needed in Christian speculative fiction. The necessity of conflict and disasters is a result of sin. I believe that Christian authors are called to share the truth of these matters and share the true spiritual options available in reality. Entertaining books using the world’s formula are not going away—at least not before the millennium—but we should write books filled with the Truth.

Yes, it is difficult. But, on the other hand, what a joy it is to be given the opportunity to write books of true power. We live in a time where it is even possible to publish these books. I wonder how long that will last?

Thanks, David!

I applaud you for what you’re trying to do. But whenever anyone tries to write God, I start getting squirmy. God is a real person. Just like when you write a real person into a book, you have to be extremely careful how you portray them, or you can be accused of libel/slander. Why do we think we can get away with this with God? He’s real. If I were to take a fantasy novel and write Kanye West into it, I think people might get squirmy in the same way. “Yep. Kanye West. Same clothes. Same music. But FANTASY.”

I hear you. Squirmy is how I feel, too. That’s why I’m usually praying while I write about Him. (“Dear God, please let me get this right…And please no smiting.”)

But I understand your discomfort! It’s a touchy subject.

I agree with it being hard to write God into a story. I would put it this way to all who would condemn or frown: what interactions have you had with God in your OWN life? How has He spoken to you? Does He always “spout” Scripture? Or does He speak to the heart, the situation at hand? He does in my life. When I write Him into my novels, it is His interactions with me that I write. People can argue many things, but they can’t argue your experience. Write on, brother.

Colleen, I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. When we share what we sense God doing in our lives, even what we believe he is saying to us, we represent him to the world. And he wants us to do that. True (to speak to Kessie’s point), perhaps many of us are not careful enough when we bear witness to what we believe he is doing. That IS a dangerous thing indeed, and we should tread carefully.

As for me, I’ll keep doing my best to write of his character in a way I believe is consistent with how he reveals himself to us through his Word and through my experiences.