The Car-Universe Without A Motor, part 12: Conclusion

The notion that atheists tend to have of the past is that people used to be frightfully ignorant. They believed in gods and demons and eventually one God because they had no idea how the universe really works. Science has pushed back the veil of ignorance, they would say, and revealed that things once was attributed to supernatural forces wind up being nothing more than natural laws in action, an unthinking universe following (or paralleling) mathematical formulas to generate all that we see around us. They further would add (most of them) that science has established the nature of the universe as a fact–that while there still might be a few issues to work out, it is certain that the universe generated itself–that most of the mechanisms of how it would do so are based on known natural laws, with any gaps in what we know being rather minor issues that surely will eventually be resolved.

They’d say that adding a Creator to the discussion only complicates things. Doing so first begs the question of “where did God come from” and in fact adds nothing to simplifying the understanding of the universe (they would say). To discuss God (they would say), we first need really solid evidence that God exists, and only after receiving that evidence can we consider God as part of the process that made the universe.

When challenged with certain highly improbable events in past history of the cosmos, they mostly refer to the concept of the multiverse combined with the anthropic principle to reply. If there are an innumerable teeming host of realities, as multiverse theories suggest, then surely one would produce observers who could notice how unusual our reality is, as the anthropic principle indicates.

The problem with this viewpoint is its riddled with contradictions. And also, modern science doesn’t back it up.

Let’s tackle the second point first. Which means taking the science involved seriously, as reporting true facts (verses arguing science is wrong)–does the understanding of science support the above view, that God is simply unnecessary?

Or, is it true that science basically understands the universe, with only a few gaps in our understanding remaining?

As documented in this series of posts, what science actually reports about the universe is as follows:

The universe has an unknown origin that produced laws of physics that have no natural reason to be what they are and any known process of making matter should have created an equal amount of antimatter, but didn’t (see part 4 of this series). The early universe expanded very smoothly and evenly for reasons no one can adequately explain (see part 3), produced a massive amount of totally unobserved and so far unobservable matter (see part 6) and which also produced “dark” energy and an observed galactic motion that’s challenged because it doesn’t match the paradigm of scientists (part 7). And which produced life out of non-life (part 10) and consciousness (part 11).

So let’s make sure we’ve got all this straight:

So the basic laws of physics, with their 19 different unrelated constants, are essentially unexplained right now? And no one knows what happened to the missing antimatter that was supposed to 50% of all that exists? No one can explain satisfactorily the universe beginning with such low entropy? No one can explain literally 95% of what the universe is thought to be made of? Life coming from non-life is treated as a problem that’s already solved, but in fact, isn’t anywhere close to being explained? And nobody can really explain the hard problem of consciousness at all, and everybody who is an expert in this field acknowledges that this is an issue?

All of that summed up does not sound to me like a universe that’s basically explained, that only has a few gaps that need to be cleared up. It sounds like ideas with gaping holes that essentially don’t work. (Maybe someday we can imagine that these ideas will work, but to think they do today is wishful thinking in the extreme.)

It should be laughable to suggest science can explain all that exists without referring to (a) supernatural being(s). Er, no, actually, it can’t. Not even close. Again, 95% of the substance of the universe as understood by modern science is unexplained, to say nothing of problems with origins of the universe. Ninety-five percent unexplained. Even if we were talking about 5% unexplained, we’d have to admit science is missing something very important–but with only 5% explained? That should be seen as a much more serious problem than it usually is seen.

If the idea that science can explain basically everything and essentially has already done so is that far out of touch with reality, where did the idea come from in the first place? From the history of science, from how things appeared to be in science circa 1900, as explained in part 5 of this series. Even though science has made more discoveries since 1900, including discoveries that make it clear the universe is much more mysterious than it once was thought to be, the attitude that we’ve-just-about-got-it-all-figured-out-and-don’t-need-to-talk-about-God persists among many scientists and even more so among people who report about science. For historical reasons.

“Well, then, adding God surely doesn’t help the confusion we face,” an atheist might reply. “It just adds one more confusing element to an already difficult bunch of things.”

This is where the analogy adopted in this series comes in. If we throw in the idea of God, does doing so just add one more unexplained thing to the mix of already unexplained things? Is it really insane to imagine a car driving uphill, as laid out in part 2 of this series (and introduced by part 1) needing a motor? Is that bad reasoning because it adds a part that humans under some circumstances would not have been able to explain (say in Ancient Greece)? Or should we insist that the “car” must have rolled by inertia alone, even if doing the equivalent of going uphill? Does it make sense to insist in the face of evidence to the contrary that the universe came about by the laws of the physics doing what they normally do, like wagon or a soapbox car rolling downhill?

A car with a motor does not invalidate the laws of physics, by the way. It just calls upon principles of physics beyond those that would be available to people who lived before motors were invented. Likewise, while there are ideas about supernatural beings that would invalidate physics, violating physics is not a necessary part of theism. In fact, it’s quite natural to think of a Creator organizing and putting into place the laws of physics–which does not require that he violate them–and then making use of the laws, including especially using quantum “randomness” to make highly improbable events come to pass. Even things we might otherwise consider miracles.

So the idea of God is not anti-science. In fact, belief in God is wholly compatible with a material universe separate from ourselves, a universe we can study, a universe that has a logical order, even if that order shows signs of being beyond human understanding.

As for the idea we need really solid evidence of his existence before we can even talk about God, how is the evidence for the multiverse + anthropic principle (discussed in part 8 of this series) any better than evidence for the existence of God? If really solid evidence is actually needed prior to even considering an idea, then nobody would ever be talking about a multiverse (as many top scientists are), because no other universe has ever been observed. Other universes are proposed not because they’ve been directly detected, but because they would explain some basic ideas about reality. Which is exactly what proposing that God exists does.

So, comparing the two ideas that make sense to think about even if we have no direct evidence for them, what makes more sense, a multiverse or a Creator God?

The idea of an enormously unlikely universe coming about because the multiverse had so many chances to generate it that eventually all things just turned out right (after in effect trying and trying and trying)–that idea cancels itself out. Why? Because such a level of randomness would much more likely produce a Boltzmann brain matrix (part 9 of this series) than a physical universe. And if we are all in a Boltzmann brain, nothing is real and science would no longer make any sense at all. So a vastly improbable universe producing itself after innumerable repeated attempts is actually an intellectual dead end. Self-defeating.

We can also observe that a multiverse plus anthropic principle requires all the weirdness of the universe to be separate, unrelated, random events–the universe winning the cosmic jackpot over and over again on unrelated issues. Or we can think that a single cause explains all the randomness–that with just one idea (God), whose origins we admittedly cannot explain, we do better than by imagining multiverses whose origins we cannot explain, laws of physics we cannot explain, a preponderance of matter over antimatter we cannot explain, as well as expansion of the universe, dark matter, dark energy, life, and consciousness we cannot explain.

Which idea is simpler, more logical, more straightforward? A host of unconnected mysteries? Or one Mystery? One God?

So the universe actually makes more rational sense when you include talking about God than if you exclude God.

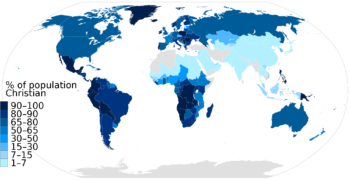

For some countries on this map, the actual percentage of practicing Christians is lower. For others, especially places where Christians face persecution, the actual number of Christians is higher. Still–Christian communities exist worldwide.

It’s in truth beyond the scope of this series to say which religion of Earth best represents the Creator who causes the universe make more sense than it would without a Creator. But it would be best, if we are to respect science, to think of a system that portrays God generating a universe separate from himself, a reality that physically exists–which generally rules out Eastern religions. And it would also be helpful to think of a religion (assuming God wants us to know it) that would eventually become known throughout the entire world–which really only applies to Christianity.

This series of posts ends here. Since this particular article summarizes and drives home the point of all the rest, Christian readers, please share this page with atheist friends. This post has links back to all the previous posts, which in turn have links to various articles on science, for any person who is interested enough to invest the time to fully examine what I’ve said.

Atheists or anyone else who sees this and wishes to comment, feel free to do so. I will gladly do all I can to answer any questions or comments. Thanks for listening.

Thanks for the great read Travis; the series was great. As a thermodynamics instructor, I finished the term by rehashing a lot of our fundamentals and what we’ve learned to model, but add the caveat “Hey, it’s great that you can now mathematically calculate adiabatic flame temperatures, but don’t forget the wonder this stuff. There’s nothing more intimate than a candle between two lovers.” I appreciate the science. I find confirmation of my faith in the research and publication of findings. Yet, I know this was all created by a God who wants us to continue to find wonder in it all. That’s a hard thing to describe to someone who’s only focused on “answers”, so thank you for helping to keep both parts balanced.

Why thank you, my fellow Travis. 🙂

I should add that I’m quite impressed that you’re a thermodynamics instructor. What did you specifically think of me talking about the low entropy expansion of the universe in part 3? I mention I got that concept from Roger Penrose’s Cycles of Time, and while I think I understood what I read, I’m keenly interested in your thoughts on the topic.