Speculative Fiction Writer’s Guide to War, Part 2: Balance of Power

Readers, the Guide to War continues! With Balance of Power this time–though the title doesn’t quite mean what it seems to mean.

Note that I will be leading off these topics with commentary that fellow author Travis Chapman (who, by the way, is an instructor of Nuclear Engineering and Thermodynamics at the US Naval Academy) is going to review and tweak, to which he will add specific “case studies” or illustrations that I will review and tweak, my words at the beginning of a post that will transition into his words at the end.

To get back to “balance of power,” please remember that the first post I wrote on this topic I now wish I’d called “part 1, Basic Drives” (or maybe “Basic Impulses”) because I tried to identify the root urges that cause people to organize themselves to fight. That is, what it is they are trying to achieve or obtain.

With the title “Balance of Power” I’m picking out the key element of what I may call in the book “Reasons for War” (or maybe “Reasoning Leading to War”)–but which I won’t do now because I used “Reasons” in the last post. The particular phrase “balance of power” is getting special attention because something happens to groups of human beings, whether tribes, kingdoms, or large modern nations, when there are a number of them in contact with one another and war is a possibility.

Nations (or tribes, etc.) in such cases have to pay careful attention to not just to what they want, what drives them in the direction of seeking war–they have to pay careful attention to their own relative power verses their enemy or enemies. That means they need to be able to evaluate the nation they plan to go to war with in terms of its ability to fight–but they have to keep in mind what other nations around them are doing, in case any of them might intervene, lest their declaration of war end in disaster.

This kind of reasoning is briefly alluded to in the New Testament (Luke 14:31-33), in which Jesus mentions how a king calculates if he can beat an army of 20,000 with 10,000 soldiers and sends off a delegation of peace if he can’t (Jesus used this kind of calculation to illustrate a point about being a Christian disciple). This case is representative of the simplest possible kind of war–one nation against one nation.

Credit: Hendrik Willem Van Loon

Note though that it was absolutely normal 2,000 years ago (and even long before that) for nations to engage in calculations of war regarding a wide variety of things, including in particular the balance of power. A great deal of military strategy involves (and has historically involved) considerations of how one particular nation sizes itself up against others–the minimum calculation stemming from one nation verses one other, but which in most cases extends to include other nations (tribes, etc.) in the area. Because with very few exceptions, humans fear all their neighbors uniting against them.

This leads to a number of observations, the first of which was alluded to by in Luke 14:

1. A nation will generally negotiate with an aggressor nation because of fears of losing a war. Or if they feel they could win the war, but the cost of winning is too high.

So while some people claim human beings naturally negotiate and then go to war when the negotiations are unsuccessful, the actual situation is more complex. Just going to war without any negotiation seems to be the first impulse of warlike nations–but a rational analysis that they could lose the war (which provokes healthy fear), brings them to the negotiation table. And only then, after negotiations are developed as an instrument to avoid the bad consequences of war (but not to avoid conflict itself) does a breakdown in negotiations start a war.

2. At the risk of sounding obvious (but for a purpose), nations generally choose to engage in war when they believe they can win, when the balance of power is in their favor. No human group goes to war simply because they have a military that’s superior (or perceived superior) to a potential enemy. But once the basic impulses (or reasons) for war as explained in the last post come into play, nations with superior military forces are much more likely to engage in war than weaker nations. This idea brings a couple of interesting corollaries:

a. Totally pacifistic groups that survive as such generally have little impact on the balance of power among surrounding nations–that is, often enough, being weak reinforces being meek.

b. Nations are more successful with negotiations when they don’t need them (because they are strong enough to win anyway).

c. Assessing the power of one’s own nation versus that of other nations is a major activity for military planners, because it’s vital to know if ten thousand really can beat twenty thousand.

3. Nations sometimes decide to go to war because they miscalculate the balance of power, especially in overestimating themselves against their enemy(ies). This is why Sun Tzu in the classic Chinese work on warfare, The Art of War, lists spies as the most important part of any Army (The Art of War, chapter 13)–because a good spy network can determine if circumstances justify warfare (or if they don’t).

The WWI Balance of Power Chain Reaction–from a public domain cartoon of the period.

4. Nations often seek alliances with other nations if they perceive themselves to be too weak to maintain a balance of power on their own. Once a balance of power is established among groups of nations through alliances so that both sides or all sides see themselves are roughly equal to one another, they are less likely to go to war. Yet, as in World War I, this creates a situation in which a single relatively small incident can cause an entire alliance to go to war over any particular friction between any of the various parts of the coalitions involved. (As the number of relationships grows, the chance of a spark does not grow proportionally, it’s more like exponential growth.)

So a great deal of activity among nations, both in the real world and in fiction, seeks to establish or maintain a balance of power–and when they fail to do so–or even if they succeed, the problems stemming from balance of power considerations often lead to warfare.

Note when we’re talking about balance of power at the national level, there are three basic ways a nation can evaluate itself: 1) Below average to some degree, 2) at parity with surrounding nations, and 3) being in a state of greater power. “Power” might not be limited to ability to conduct warfare–it can also mean economic power, perceived cultural or ethical power or position, numerical power (greater population or controlled territory), or geographic power (i.e.,holding territory that has the most value, like key mountain passes or navigable waters). Obviously a nation (or any group of nations) might possess a bit of any of these, or all of them.

So with the three basic tiers mentioned above, we see the following inherent conflicts:

- Lower nations trying to bring down those in higher positions

- Lower trying to achieve parity with others

- Lower fighting for the scraps between each other–or adopting a pacifistic attitude

- Higher stations trying to hold their positions against internal disruption

- Higher stations trying to eliminate potential competition from below

- Parity nations try to climb one rung higher than a peer

- Parity nation trying to pull up a lower nation to their level (often via an alliance or coalition)

This complex set of relationships above is in fact based on one nation against another at any given moment and doesn’t list every possible situation: the dynamics of alliances and coalitions are generally even more complicated, but have many of the same elements. Both sides of a potential conflict have a story to tell about why they chose to go to war and their own perception of how things reached the point of conflict–which provides plenty of story material for any author.

Travis C here. Any nation (and we’ll assume a nation here, but it could be any organization of entities) will have a certain calculus going on as they consider their position on the hierarchy of power. You should realize it’s calculus too, not just basic algebra, and a good deal of statistics. In the modern world, it is often literally math, with military planners doing calculations of force, weapon effects, measuring changing conditions, and mapping varied courses of action and their likelihood of success or failure. For fantasy literature the calculus will likely happen at the planning table and in the minds of key stakeholders weighing the odds (think of King Theoden stating Rohan will not risk open war). I propose that in most science fiction settings you might add an element of AI support to our modern practices (cue C3PO calculating the odds). Only you will know to what degree you’ll need to analyze all sides of the conflict to determine the impact it has on your story.

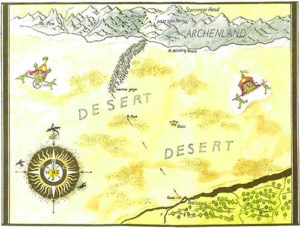

The desert between Calormen and Archenland.

One of my favorite examples of this calculus is found in C.S Lewis’ A Horse and His Boy. We witness a peek behind the curtain as Lewis truly shows, not tells, the analysis of nations when we meet Shasta in the company of the Narnians while in the nation Calormen’s capital, Tashbaan. The Narnians suspect Prince Rabadash of ill dealings and speculate what might occur should they escape Tashbaan. Narnia is no match for Calormen sword for sword (differing relative positions of martial power). However, Narnia and ally Archenland are protected from the brunt of Calormen’s army by geography. To launch a major campaign against Narnia, Calormen must either cross a vast desert (logistically challenging) or embark by sea for an invasion (likely to be met with resistance ashore and hard to pull off at such a distance). The Narnians conclude the risks associated with escape are worth it; they doubt Calormen will retaliate in any meaningful way.

Now we jump ahead and learn the Tisroc, supreme ruler of Calormen, will back a minor expedition by Prince Rabadash to take the small kingdom of Archenland by way of the same desert. A small force may successfully cross the desert and maintain sufficient strength to overthrow an unexpecting Archenland. The Tisroc, without Prince Rabadash’s knowledge, accedes the venture may not carry, but if it does and Rabadash conquers Archenland, then Calormen can slowly build up a military force on Narnia’s doorstep, making way for a future campaign. He also weighs his relative political strength in Tashbaan when he admits that should Rabadash fail, he’ll write the whole thing off as a boy’s rash temper. Surely he knows the Calormen news cycle to assure himself of an evening headline “Wild Prince Rabadash Goes Off The Handle; Archenland Protests Military Exercise In Desert” is one he can recover from.

The Tisroc…

Lewis uses the varied geography between Tashbaan and Castle Anvard to drive the major characters until we reach a satisfying conclusion. We see the roles of individuals, small units, and ultimately three major nations, two in alliance, all collide in a beautiful story that displays evidence of a well founded conflict between nations.

It’s also worth noting that Lewis plants a seed here. The argument of the Tisroc, that Narnia can be taken by seemingly unnoticed infiltration, comes to pass in The Last Battle. Small gatherings of Calormen, under the guise of merchants, slowly gain a foothold in Narnia and ultimately allow the receipt of Calormen’s army by sea in the taking of Cair Paravel. A strong analog to the way that seemingly minor, yet persistent, sin can gain a foothold in our lives.

Since Travis P opened us, I’ll close this one out. We’ve combined efforts and hope to bring you an outstanding series on the nature, conduct, and consequences of the spectrum of conflict we call war. We have an outline of topics to cover in a shared voice. We hope to do this through two contexts: first, as writers of speculative fiction, and second, as authors of fantasy and science fiction in particular.

Hopefully you can keep your Travises straight. It’s going to be a great journey together!

Great post, guys! Thanks for giving us a behind-the-door look at what happens before war ensues.

Tho I’m not sure if you should accredit Travis C on this topic by way of saying that he teaches ENGINEERING at the Naval Academy, but still better than implying by omission that he teaches tactics or history there. Means we have to evaluate his input on its own merits rather than his authority.

Mostly the joke is lol engineers think they know everything.

I’m simply saying my fellow Travis is a smart and accomplished guy. And, for what it’s worth, he is already keeping me from wandering too far afield from standard thinking on this subject. (Being an out-of-the-box thinker is not always a good thing–sometimes the answer is actually IN the box. 🙂 )

I’ll upvote that! The irony is never lost on me; I love engineering and systematic, logical thinking, and, when given the outlet, I love writing and using my creative side. Mom & Dad always knew to buy both Legos & a drawing pad for Christmas! If it makes you feel better, I teach a breed of thermodynamics for warfighters, so they know how their machines are aiding their tactics (grins)

Very interesting. One of the fun parts is thinking about how different groups(or even individuals) might try to maintain their balance of power. Encouraging or ignoring certain conflicts in other nations, for instance, or even trying to encourage certain nations to remain neutral instead of joining the fray would be just a few ways. (And then, depending on the circumstances, attacking/taking advantage of the nation busy with its civil war)

Actually, that was kind of a concern in Naruto and((Spoiler alert)) a reason why the Uchiha clan got eliminated: The Uchiha were going to rebel, and that would start a civil war, which would greatly weaken their village and nation. As a result, other nations would want to take advantage of the situation and attack the nation. Rather than risk that, the higher ups decided to destroy the Uchiha before they could attack and endanger their village and nation’s welfare.

Love The Horse and His Boy, so it’s fun to see it used as an example 🙂

Linking this as well since it’s on war and people might find it interesting:

Shad’s mention of the study of WW2 (where most people weren’t shooting at anyone) is something I would disagree with–not in me saying that it didn’t happen, but disagreeing that it only happened in WW2. Not true–in fact, studies of earlier wars also revealed the same pattern, including the US Civil War.

Humans show a general pattern of not liking warfare–however, culture does make a difference, as Shad correctly points out. Some cultures venerate war, which does make it easier for people to push past a natural aversion to killing. He also points out that people were used to death and that made it easier for them to accept death on the battlefield–yes, I agree with that.

His comments on getting rich were quite good. In fact, the things he said applied to all wars prior to modern times–and even for modern wars, taking lands and goods of other nations has been a major motivation for warfare, no matter how much people would appeal to their cause being right as a justification for war.

Thanks Autumn! It remains my personal favorite of the series (only slightly edging ahead of The Last Battle). King Lune represents the kind of man I want to be.

🙂

I think Horse and His Boy has some of the best characters in the series. Aravis is probably my fave, though I like all the others as well. Also, that book does the travel scenes well enough that they didn’t bore me, like they tend to in other stories.

I love The Last Battle, too. Ironically, it was the first Narnia book I ever read. Back then it was very common for me to read book series out of order.

Again, as the author of three traditionally-published speculative fiction novels and the self-published author of a ten-novel series about the air war in the Pacific, 1941-42, I find this fascinating and instructive. What I didn’t see, however, is how often a weaker country will attack a stronger country (or coalition of countries), confident in their “martial spirit” to make up for a weakness in overall forces. Four examples can be found in the 20th Century: Germany (WW-I), Germany (WW-II), Japan (WW-II) and North Korea.

In the first global war, Germany counted on a two-front war. Their plan was to hold off Russia (Tannenberg) in the east while they used a modified Schlieffen Plan to overcome France before Britain could become a factor, then use their strong internal railroad system to rush troops from the now-peaceful Western Front to take on the Czar. This almost worked, but it didn’t, and after six weeks of unstoppable aggression, they were forced into trench warfare on both fronts. Having beaten France quickly in their last war (1870-71) and taken and held Alsace-Lorraine by treaty after a fast war, this was not out of the realm of possibility. However, when the plan failed, a sensible Germany would have sued for peace (they occupied most of Northeastern France and were in a good position to talk armistice). Instead, national pride led to four years of war and devastation beyond comprehension.

Fast forward two decades and Hitler swore that he’d never fight a two-front war … until, after beating France in six weeks as the Kaiser had planned in 1915, he backed out of his planned invasion of England after Churchill refused terms. Instead of building up an invasion force in France and maintaining an air war until England crumpled, he moved his forces East, betting on another six-week war that would allow him to control European Russia, giving him the resources needed to turn back against England. However, his 1939 peace treaty with Stalin gave him those resources without a war, showing that he failed to learn the signal lesson from the first global war – Germany cannot win a two-front war.

Then, adding insult to injury, he gratuitously declared war on the US on December 11, 1941, when his treaty with Japan required no such thing, and when he had no casus belli to justify such an action. Between June 22nd and December 11th, Hitler decided to go to war with both of the two largest industrialized countries on earth – each country which then proceeded to out-produce Hitler and ALL his allies in terms of tanks and aircraft. Further, Stalin had seemingly inexhaustible supplies of men, allowing him to essentially lose two entire armies while learning how to fight the Germans, then to raise a third army large enough to defeat the bulk of Hitler’s ground forces.

So twice within two decades, Germany created wars against coalitions of larger allies which they could not hope to beat based on numbers (soldiers or productivity), trusting instead on martial spirit and superior technology, neither of which were German exclusives.

Also in 1941, Japan chose to attack the United States when it wasn’t necessary. Because of the strong anti-war movement in America in 1941 (the America Firsters), Roosevelt would have had the devil’s own time persuading Congress to go to war against Japan because Japan attacked both Great Britain (Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaya) and Holland (Dutch East Indies). Japan was vastly smaller than the US (about the size of California, with not much more than half the population, and with almost no natural resources – let alone an internal infrastructure (rail lines, roads) still mired in the 19th century. America’s industrial might was no surprise to Japan – that can’t be an excuse. At the time, the Japanese Pacific Fleet was larger than the US Pacific Fleet, but that was about to change (the Essex carriers and Iowa battleships were already on the construction ways), and America could in a month outproduce Japan’s aircraft production for a year. There was no match.

Japan depended on one thing, and it was the wrong thing (in two ways). In every war since the Revolution (with the sole exception of the Civil War), America settled their wars at the negotiating table, which made Japan think that perhaps they could settle the war (in their favor) at the table. However, whenever the US negotiated (with the possible, debatable exception of 1812), it did so from strength, not weakness. Mistake number one. Mistake number two is that the one war that ended with unconditional surrender was the one that the other side provoked with an unwarranted assault (the US Civil War, South Carolina’s firing on Fort Sumter without cause or provocation). It can also be argued that the Civil War was, for the Union, an existential war (as we faced in the Cold War), because to lose the war was to lose the Union (as it had been). Still, we did have a tradition of unconditional surrender, and by launching a surprise attack while supposedly negotiating in good faith, Japan had demonstrated a “treachery” that the US sense of fair play would not tolerate.

Also, Japan forgot that America did not fight for empire. The settlements with Mexico (1848, when we bought and paid for the land we took from Santa Ana) and 1898 (basically the same deal, but with Spain) notwithstanding, in the first global war, America sacrificed hugely in blood and treasure for equitable principles and freedom of all people, with no material gain for the US. This allowed us to fight a noble, just war – and when Japan provoked us with a raw territorial land-grab, we could trot out that Great White Horse and mount him again for another just war.

Under no circumstances could Japan win a modern tech-war against the largest economy on earth, backed up by (as allies) the third largest economy (UK). Yet they thought they could, and were the most thoroughly devastated loser in modern warfare’s history. Such is hubris (especially since Japan probably could have worked out a deal with the Dutch East Indies to buy the oil instead of conquering them and take it – but that’s beside the point).

Finally, North Korea. Listening to the US diplomat that specifically excluded South Korea from America’s sphere of influence (reinforced to Stalin by a broken US diplomatic code that said basically the same thing), they decided that it was safe to attack South Korea while US forces remained in-country. Big mistake. Regardless of what diplomats say when there’s no shooting, once American soldiers come under fire, the US tends to react with less than equanimity. Which meant that within a day or two, Truman started sending reinforcements, even while evacuating US personnel from Seoul via air (and defending the airfields with US fighters based in Japan. The results were the successful defense at Pusan, the successful invasion at Inchon, the drive to the Chosin, China’s intrusion into the war (something agreed to in advance of the war by Stalin and Mao), and a three-year stalemate that wound up with status quo ante. In the process, North Korea was bombed into the stone age, almost literally, creating havoc in what could have been a reasonably prosperous third-world country.

Bottom line – time and again, weaker powers think that through strategem or martial spirit (or some equivalent thereof), they can defeat larger powers or coalitions of powers. Except for a very short war that begins and ends before the larger power can mobilize, this never seems to work.