Shallow Reasons To Support ‘Narnia’ 1

Today I feel like a good old-fashioned, and I hope Christ-exalting, rant. This one focuses on popular reasons to love The Chronicles of Narnia and similar stories. Such reasons miss the beauty of a literary forest, in favor of esoteric, specific Bible-quoting spiritual symbols and Allegories that are supposedly carved into the trees — if you look very closely. (Or rather, you teach children to look, because you assume Narnia is only for children’s Moral Benefit.)

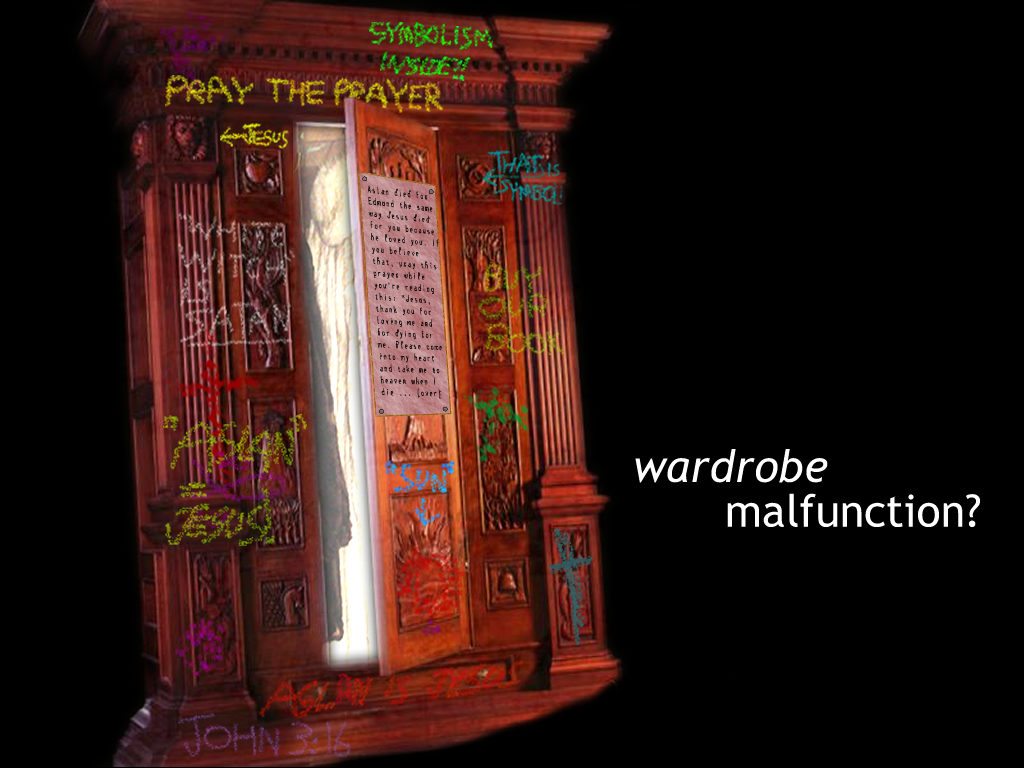

Don’t put silly spray paint all over the Wardrobe. Its magic world within, and (in the film) the symbols carven without, should first share their own story.

Here, and in part 2, I’ll base my critique on this article. Its author is Peter Hammond. I only recognize the name and I’m sure he means well. He gets plenty right, such as that Narnia is a “supposal.” But then he sadly goes off violating fantasy-story “hermeneutics” in a way that no evangelical Christian would do — or should do — with a certain other Book we enjoy.

Do I pick on this because these flawed Narnia justifications are irksome, and because I just finished a local-church reading group for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe? Absolutely.

Yet my main reason is because this is a question of worship.

I mean this: that if you view a story like LWW in this way, you will worship God less.

A sermon parallel

Does Aslan’s death signify Christ’s? Yes. Does the story contain symbols and allegories? Yes. Do Christians overreact to silly or liberal “metaphorical” approaches to Scripture and thus claim the “literal meaning” precludes any symbols, callbacks, or parallels in the Story? Yes.

But let us take a famous Bible verse, such as John 3:16. I read this verse, in context, aloud in front of a group of people. I have no idea if these are “professional” Christians, new Christians, or Biblically ignorant or Biblically fluent non-Christians. So I read aloud: “For God so loved the world …” and so on. Let us say I fix on the meaning of the word world. I do a study on the differences between the Greek aion (age, I believe) and kosmos (physical creation). I discuss other uses, symbols, parallels, and more. Then I end with, “Let us pray.”

Is this bad? No; we need such deep-delving. Is this untruthful? Again, no. So what’s wrong?

This: I should have first proclaimed the text’s central, beautiful truth. “Listen! God loves His creation. According to His love, He gave His only Son so that all those who believe in Him will not be condemned but live forever. What an amazing Story about an amazing God! Has He saved you? If so, you will want to respond to Him. Exult in Him. Delight in His beauties.”

Now watch what occurs when someone approaches a story such as LWW, surely with good intentions, but with primarily a fill-out-symbolic-checklists-on-behalf-of-others emphasis.

First, what does that approach miss?

- In place of a spirit of worshipful delight and wonder is an air of stiff approval.

- In place of having the heart of a child is having the heart of a child’s Instructor.

- In place of an eye for beauties in the subcreator’s writing, and the Beauty of the Creator Himself, is a wandering glance that seeks Obviously Practical Truths.

- In place of humility “under” the story is a salvage effort to seek parts for Good Use.

Narnia vs. certain other fantasy stories

Unfortunately, because of the success of the “Harry Potter” series, many have assumed that the “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe” is something similar. However, while Lewis’s “Chronicles of Narnia” have a Christian worldview, the “Harry Potter” books and films are occultic.

One should not gloss over such LWW critics’ alarms over “occultic” elements in that story. Without directly addressing those and defending from Scripture a better understanding of sin’s real source (not the world, but our hearts) and a practice of “taking captive” “pagan” myths, any “but it’s allegory”-based defense of Narnia seems like un-discerning distraction.

One should not gloss over such LWW critics’ alarms over “occultic” elements in that story. Without directly addressing those and defending from Scripture a better understanding of sin’s real source (not the world, but our hearts) and a practice of “taking captive” “pagan” myths, any “but it’s allegory”-based defense of Narnia seems like un-discerning distraction.

As for Harry Potter [HP], in the writer’s defense, he seems to have written this in 2005, two years before the HP series ended with a brilliant echo of Christ’s sacrifice and defeat of evil. Yet in the author’s offense, he repeats myths about the HP series even by that time.

C.S. Lewis made clear in his writings that it is wrong to use magic.

The writer gives no source for this claim. I don’t recall Lewis speaking on the topic of real-world “magic” (or defining what “using” it would look like in reality). Discerning readers must tangle with Lewis’s love of “occult” myths and fairy-stories, to understand his views.

Magic is forbidden in the Bible (Deuteronomy 18:8-13; Leviticus 19:31; Revelation 21:8).

It would help to define briefly why God forbids this “magic.” It is not imaginary magic that only exists in folklore, but willful attempts to reject God’s power and means of revelation in favor of our own attempts to predict the future or control our lives. By this higher standard, using devices such as Ouija boards would be wicked, but so would be “Christian” methods of divination that fear Things, or try to seek God’s secret will in “signs” to know our futures.

This writer does rightly understand Narnia’s use of “magic” to mean God’s laws or miracles.

The worlds that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien described in their novels were real worlds with real consequences and real hope. Actions have consequences. When Edmund succumbs to the temptations of the White Witch, he has to pay the consequences, or someone has to pay in his stead. In contrast, the “Harry Potter” books are thoroughly occultic.

This is incorrect. Why do Christians repeat such myths? Actions also have consequences in the Harry Potter world, and the series roundly condemns relativistic views of good and evil.

In their ontology, the world can be manipulated through magic. Things change shape. Nothing is really real. There is no need for a Saviour.

Again we see why simplistic defenses of Narnia are undiscerning. In Narnia, the world can also be “manipulated by magic,” and “things change shape.” As for “nothing is really real,” this repeats a postmodern, my-interpretation-over-the-author’s-intent mode of reading HP.

One merely has to have the right incantations and formulas to manipulate reality for one’s own selfish ends.

In Narnia, as in Harry Potter, these sinful behaviors are shown. And by the end of the Harry Potter series, they are also condemned. In either series, characters sin, learn, and change.

Violating Narnian ‘hermeneutics’

C.S. Lewis explained that: “The whole Narnia story is about Christ.” “The Magician’s Nephew” is about the Creation and how evil entered Narnia. “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe” is about the Crucifixion and Resurrection. “Prince Caspian” is about the restoration of true religion after corruption. […]

Yes and no. Behold the religious tendency to crave stamping Moral X or Moral Y or Moral Z atop a story or product. For instance, that is only one theme of The Magician’s Nephew; the story also explores human suffering, fertility and motherhood (author Michael Ward argues the story is themed after motifs based on the medieval mythology of Venus), temptation, “supposals” of other worlds, and other themes. To say “the story is about this only” neglects these other meanings. It is a flawed, fill-out-the-blank approach that also lessens worship.

This article’s writer does, however, get it right that Narnia is a “supposal.” Here he quotes Lewis accurately and favorably. Unfortunately he then ignores Lewis’s “hermeneutical” hint in favor of a “Find Deeper ‘Spiritual’ Meanings First for Our Practical Use” hermeneutic.

When the Witch confronts Aslan, she reminds him of the “deep magic” the Law that “every traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have the right to kill.” The Witch declares that by law, his blood belongs to her. All of this echoes Romans 6:23 “The wages of sin is death.” And Hebrews 9:22 “Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins.”

As noted here, the Deep Magic is similar to God’s Law, but not exact. One does not need to parse the Witch’s words or delve into symbols to discern this; one only needs to know that it is God, not Satan — or Death itself, as the Witch better reflects — who punishes sin. Any Christian defense of LWW should recognize the allegory’s limitations. Otherwise we may violate the story’s intent and read “back into” Scripture a foreign belief. (This is especially possible when people misinterpret the meaning of the character Emeth’s near-salvation in The Last Battle to believe Lewis fully endorsed a kind of “anonymous Christian” notion.)

Next week: approaches like this ignore the central intent of a story and the primary need to be first lost in its beauties and wonders, in favor of un-humble attempts to “spiritualize.”

I’m always amused that no Christian, while promoting Narnia hardcore, ever touches on the thing that disturbed us when Mom started reading it aloud. We got to the part about “Adam’s first wife Lilith” and how she wasn’t human, but Eve was. We all looked at each other and went, “Annnnnd … where is he going with this?”

I’ve since been educated in myth and I understand the Lilith reference. But to claim Narnia is a thoroughly Christian book and ignore the way scripture is “twisted” to include mythology is the same as saying Harry Potter is occultic. Both claims somewhat miss the point. There are Christian elements in Narnia, and some are allegorical. But I just hate it when Christians gush about what a wonderful spiritual story it is.

Narnia is just a good kids’ book series with some Christian allegory. It wasn’t to convert anybody. I believe it came about because the Inklings were lamenting the state of preachy, moralistic children’s literature, and how they could all write better stuff. Guess what! We’ve made their work into preachy, moralistic children’s literature!

Yes, no shallow-defending Christian ever talks about that! They just sort of blanch, shake their heads. Nothing to see here. Move on. That’s what I used to do, too. And others do it with slaughters of the Amalekites and things like that, until they wake up one day and realize they’ve been dodging it all their lives and then have a nice excuse to Reject the Faith. (Sometimes they say the adults hid this from them, but I doubt that. All the details are right there in the Book. And skeptics quote them.)

Understanding Lewis’s views of mythology and redeeming “pagan” elements is absolutely essential to getting truly deeper into the series. Lewis is not your generic evangelical who may think it’s “deep” to make up a different name for Jesus or the Apostle Peter or Mary and Martha, and then stick swords in their hands.

I do believe the Narnia series is still at the top of Christ-exalting fantasy, and better than most. Where I object, along with you, is when people act like Narnia is the sole exception to what is otherwise a genre of story steeped in “occult” material. Narnia is unique, yes, but not that unique, and not for the reasons folks try to cite!

In Lewis’s view, it was more than that, though. This is where I start to push back against myself. I don’t mean to imply that Narnia is just as “secular” as another series, or that no symbols are to be found in it. However, I do believe we wrongly identify it primarily, or even secondarily, as being or having “allegory.”

Hammond in his article rightly said it is a “supposal” of Jesus creating and acting in another world, but evidently he wasn’t interested in pursuing or describing what that means. No, good sir, if you believe it is a “supposal,” that means that in the story-world — working according to its “rules” and not trying to twist the magic for yourself — it is real. There is a real “our world” and a real Narnia. It’s not “allegory” and all those one-to-one correspondences are the most outlandish speculation.

(In part 2, Aug. 16, I’ll more specifically explore the supposed correspondences.)

I do agree with Hammond when he correctly says the stories were all about Jesus. They just weren’t about Him in the memorized-facts, it’s-all-just-a-Bible-story-with-other-language fashion he incorrectly assumes they must be.

Alack, reprehensible irony.

When I read an analysis of The Horse and his Boy that said it was a retelling of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, I inwardly screamed bloody murder. I’ve only ever read that in one place. Do you think it is?

Because if a person fleeing the country with critical information about an invasion is a retelling of Moses and the red sea, then half of all spy thrillers are Moses retellings.

While this parallel would be clutching at straws, it’s funny that you should say many spy thrillers are Moses retellings because I’ve heard that one before. There may even be some truth in it.

The Moses Identity.

The Hebrew Ultimatum.

The Born-Again Supremacy.

I have a tendency to over-allegorize stories, much like Peter Hammond did in that article. Recently, I’ve realized that trying to make connections with story-elements is a wearying task, and one that is never certain. You can’t find an allegory or analogy unless you know the material that is being referred to; therefore, if the primary value of a work is allegorical, you can’t really benefit from it without being as smart as its author.

Peter Hammond wrote:

Peter Hammond wrote:

I actually think he has a point, even though I agree that he was wrong to accuse Harry Potter. Lewis’s and Tolkien’s worlds both feel much more real and spiritual than Rowling’s, because Rowling doesn’t seem as sensitive to the sense of natural wonder. I’m sure turning beetles into buttons or rats into snuffboxes is not supposed to have any particular significance; it’s not supposed to imply that we should be able to force God’s creation to do our will or that nothing has definite meaning. That silly, light-hearted magic in Harry Potter doesn’t take itself seriously enough to consider the ramifications. This doesn’t make it evil, but in my opinion, it makes it worse as fantasy fiction that either LotR or LWW. Lewis was very sensitive to the philosophical and spiritual ramifications of everything in his works.

(Apologies for messing up my previous comment.)

That’s one of my issues with HP: the magic is not taken seriously enough. Just as many people don’t consider the implications of technology, I suppose.

[…] part 1, I’ve tried to come up with reasons why good Christians, such as this one, […]

Some people were referring to LOTR as Biblically-based the other day, and because I was in an argumentative mood, I tried to point out the distinction between “inspired/ echoed” and “based.” I’m not sure I succeeded, but the parallels they pointed out annoyed me no end.