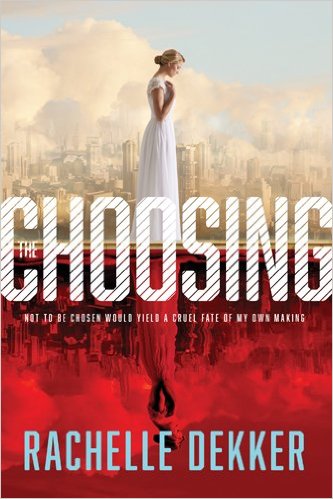

The Choosing: Worth, Truth, and Authority In The Future

In a post-apocalyptic society governed by a pseudo-Christian ruling council called the Authority, the fate of every teen girl depends upon the outcome of the ceremony that gives Rachelle Dekker’s debut YA novel its title: The Choosing.

This is the day that young men choose their brides out of a pool of eligible candidates. This is the day any leftover ladies are permanently separated from their families and condemned to a life of endless drudgery. This is the day seventeen-year-old Carrington Hale meets “a cruel fate of [her] own making”—or so the Authority calls it.

Although a path-determining rite or test is a common trope in YA dystopia, Dekker puts a new spin on the cliché by beginning the novel in media res at the moment a City Watch squadron marches into the Choosing ballroom to tear Carrington away from her family. Instead of emphasizing the ceremony itself, the focus of the book from the start is on Carrington—her confusion and fear when the Watch guards approach, her reaction toward her hard new life as a waste-management laborer, and her slowly changing views of the Authority-sanctioned ideology behind the Choosing.

The worth of both men and women—but especially women—is determined by the Choosing. According to the Authority, a woman is worthless unless a man selects her to be his wife. Moreover, the blame for not being chosen is placed squarely on the woman for failing to be “good enough.” However, even within the rigid patriarchy of the Authority, men are wronged as well. Any young man who is deemed unfit in some way to lead a family is not allowed to marry. Remko Brant, a sympathetic City Watch guard Carrington meets in the city’s manual labor district, has been barred from choosing a wife simply because he speaks with a stutter. Although Dekker represents the viewpoints of these two main characters—Carrington and Remko—in separate chapters, their voices intermingle smoothly, painting a balanced picture of the injustice both genders face.

Brainwashed into accepting the Authority’s definitions of their worth or worthlessness, Carrington and Remko try to make the best of their situations—that is, until Larkin, another Choosing ceremony reject, invites Carrington to a secret meeting led by a rebel preacher named Aaron. Despite the deadly consequences for getting caught, Carrington’s “thirst for truth” pushes her to attend the meeting. There, she hears for the first time a different message: that the Authority’s definition of her worth is false, that she is beautiful, special, and “already chosen” simply because the Father made her. This definition of identity and worth lines up with the Bible’s teaching on the nature of human beings: that we are inherently valuable simply because God created us “in his own image” (Gen. 1:27).

Beyond the confines of Aaron’s circle, however, there is some serious distorting of God’s Word taking place. To support its views on human worth, the Authority relies on a twisted version of the Bible, ironically called the Veritas (Latin for “truth”). The Authority uses the idea that the man should be the “head of the household” as justification for both the complete subordination of the wife to the husband and the marginalization of men who are supposedly incapable of leading a family. These ideas stand against the Biblical depiction of marriage as a mutually supportive “one flesh” bond between wife and husband (Mark 10:8).

As the plot moves forward, the novel’s antagonists continue to use the Veritas to justify their actions. While Carrington mulls over Aaron’s God-grounded appraisal of her worth and struggles with forbidden romantic feelings toward Remko, a serial killer is running wild in the laborer district. The killer forces several of Carrington’s fellow female workers to drink lethal amounts of bleach in the name of “cleansing” them from their sins. Apparently, the Veritas does not agree with the Bible’s assertions about salvation through grace alone (Eph. 2:8).

In addition, Isaac Knight, a member of the Authority council, uses the Veritas to justify the capital punishment of an imprisoned member of Aaron’s circle. Misapplying the intent of Romans 13:1-2, Isaac successfully lobbies for the execution of the “rebel” for treason against the Authority “that God has appointed”—that is, for openly disagreeing with the Authority’s views on worth and identity. Thus, Dekker deftly uses the tragic results of skewing the Bible to increase the tension in the second half of the book.

Since this novel is the first in a planned series of books, it ends with something of a cliff-hanger—an effective technique for piquing reader interest in the next book. However, probably as a result of the author’s need to hold back information for subsequent books, the world-building in this novel seems a bit sparse. For example, Dekker could have capitalized more on the physical location of the Authority society—the area once known as Washington, DC—more than she did, as far as visual and textural descriptions go.

Conversely, what the novel lacks in setting detail, it makes up for in characterization. Carrington and Remko are both depicted as well-rounded, sensitive individuals, despite the dismissive labels their society tries to place on them. Their budding romance is sweet and innocent—a refreshing breath amid the sultry relationships in mainstream YA dystopian novels and the soulless arranged marriages that often result from the Choosing. Finally, the discussion questions Dekker includes at the end of the novel are useful for facilitating further thinking about both the characters and the themes presented in the book, thus making this a great story not only to read on one’s own, but to share with friends.

Ultimately, whether or not Rachelle Dekker will be able to match the authorial accomplishments of her father—Christian thriller and fantasy novelist Ted Dekker—remains to be seen. However, entering the world of faith-infused speculative fiction with a novel as relevant as The Choosing seems to be a significant step in the direction of success. During our current media-saturated era in which young women are under more pressure than ever to conform to certain societal standards in order to be considered beautiful, capable, or valuable, Dekker’s debut novel is well-timed. The themes of biblical truth and God-rooted self-worth Dekker presents in The Choosing are applicable and appealing not only in a dystopian future, but also in the present day.

This seems like a more apt criticism of the sexist weirdos within Christian culture than anything in secular culture, but I am a-okay with that! Down with the patriarchy! Tear down the purity fetishism! Burn in effigy all the establishmentarian old white men! JUUUUUSTICE!