Taken Into The Dance: The Metaphysics Of ‘Interstellar’

In his sublime essay The Weight of Glory, C.S. Lewis muses that “at present we are on the outside of the world, the wrong side of the door. We discern the freshness and purity of morning, but they do not make us fresh and pure. We cannot mingle with the splendours we see. But all the leaves of the New Testament are rustling with the rumour that it will not always be so. Some day, God willing, we shall get in.”

It’s this natural human yearning for transcendence beyond mere survival that animates the latest and to-date longest film from acclaimed writer-director Christopher Nolan. Interstellar is more than a narrative conceptualization of space-travel; it’s a passionate appeal to the innate dignity of the human race, a desperate declaration of independence that grasps and claws for meaning amid a vast, echoing void. It at once elevates the viewer and consigns him to futility.

While I’ll attempt to keep plot-points relatively vague, the following review can’t help but contain spoilers. If you haven’t yet seen the film, I encourage you to set aside this review and head to a theater — preferably one with an IMAX screen (the film contains over an hour of 70mm IMAX footage which Nolan went to ridiculous lengths to capture, even mounting a camera in the nose of a Learjet). Don’t expect the film to reinforce your beliefs. Instead, prepare to be swept away by a master storyteller at the top of his game.

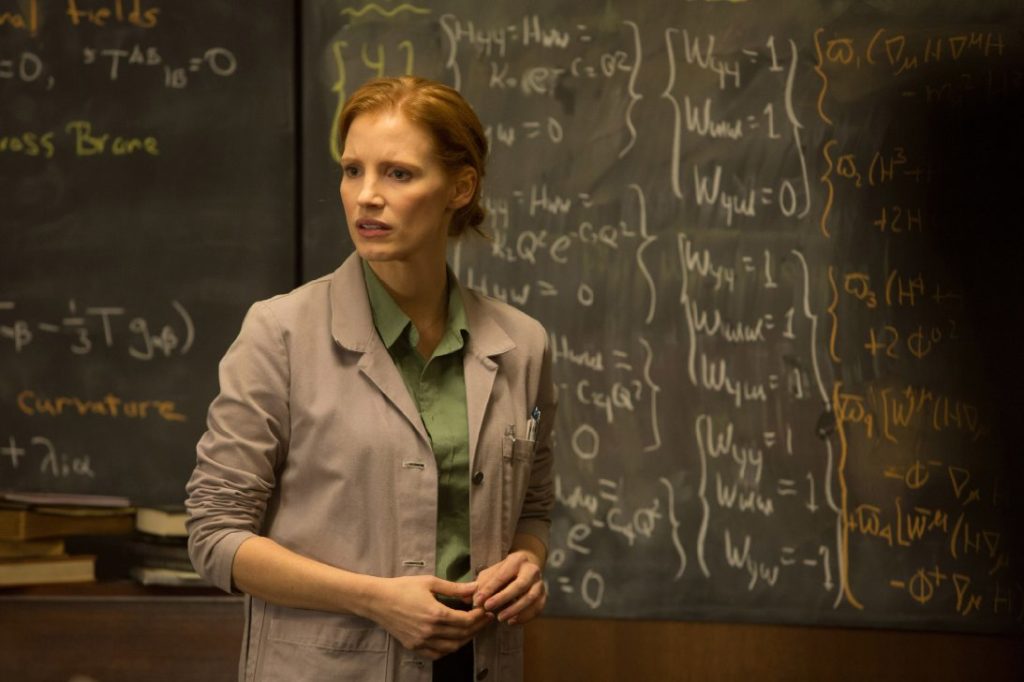

The story begins on an Earth that’s been broken. Terrible blights have ravaged all crops but corn. A perpetual dustbowl grips the planet. Ironically, it’s only in such straits that mankind’s achieved world peace: people are far too focused on their own survival to think about threatening others. Reaching for the stars is no longer an aspiration: school textbooks describe the Apollo missions as clever propaganda. And, on a nondescript farm somewhere in the American midwest, widower Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) dreams of his glorious test-pilot past while his daughter Murphy (played successively by Mackenzie Foy and Jessica Chastain) watches books fall inexplicably from her shelves and thinks dark thoughts of ghosts.

The relationship between Cooper and Murph is the pivot around which this story-world turns. When Cooper finds a coordinate pattern in the dust on Murphy’s floor, he sets out on a journey of faith that leads him to a classified government facility. There he is met by Professor Brand (Michael Caine), a theoretical physicist and the head of NASA-in-hiding, who recruits him to pilot a spacecraft through a recently-formed wormhole in an attempt to save humanity from the extinction threatened by the dissipating oxygen of Earth.

That this all sounds rather implausible is not lost on the characters involved; one of the reasons the film stays deft despite its scope is that it lampshades nearly everything. But existential desperation, combined with the apparent intervention of a higher power (for what else could manipulate gravity to first open an intergalactic door and then gather a team to step through it), convinces Brand and Cooper that the time has come to risk everything on behalf of the human race. Several expeditions have preceded this one, and their transmissions carry hope of habitable worlds beyond the spacetime warp. What Cooper and his fellow astronauts must do is to confirm that hope and return. By that time, promises Brand, he’ll have cracked the code of gravity — sought in scribbled equations enwrapping his walls — and be capable of carrying humanity’s remnant beyond the gulf of space. But he’s not there yet.

Not yet.

Murph is devastated by Cooper’s seeming desertion. His appeals to logic, to duty, to the cost incurred by love, might as well be uttered in a vacuum. Bitter is their parting. Long will it linger. It’s to the song of her sobs that he departs her room, his farm, the Earth itself in a scene of content-elision and emotional continuity poignant in its concision. It’s a strange thing to say of a three-hour film, but Interstellar wastes no time. There’s not a minute I would cut.

The words that speed our explorers on their way, intoned by Michael Caine and borne up upon Hans Zimmer’s breathless score, are not the empty promises of progress purveyed by modernist philosophers, but the primal, white-knuckled, red-faced denials of Dylan Thomas: “Do not go gentle into that good night, old age should burn and rave at close of day; rage, rage against the dying of the light.” And as their craft slips through space en route to the cosmic sinkhole behind Saturn, the immensity, the sheer weight of emptiness that surrounds them begins to press in upon our consciousness. No Field of Arbol this: they are but small sailors in an ocean of oblivion, climbers clinging to a cliff without cracks. If Earth should expire, their kind — our kind — will die. To fail now is to fail for all time.

In a spine-tingling rapture, they pass beyond the wormhole.

And now I must turn from spoilers to examine the concept of time itself, for, in this life, it is the foundation of fear. “I don’t fear death,” declares Brand, “I’m a physicist. I fear time.” Without time there can be no death, and without death there can be no ultimate loss. Time is separation. It sunders parents and children, lovers and friends, drives wedges between generations, levels the towers they build, and inexorably grinds the universe to dust. It is the power of entropy, enemy of all that draws breath. The presence of time as an antagonistic force is a commonality among stories with the power to bring me to tears, in the same way that its absence from the lives of most cartoon characters is an implied assurance to the reader of their emotional harmlessness. After all, if a character doesn’t change over time, then he’ll never leave — there’s no risk inherent in extending him love. Timelessness is sanctuary.

But on the other hand, what is life without the threat of loss? Like nothing we can imagine, that’s what. Our valuations are all tied to time, dependent on that which will steal them away, forced by the fabric of the forth dimension to prioritize some things and ignore others. Why do I spend the evening with my wife instead of with my friends? Because there isn’t enough time to do both, and I must ration this scarce resource to reflect my values. This is why we appreciate Calvin and Hobbes more, not less, for sledding into white space never to return — their every moment is now numbered and precious. And it’s why Cooper comes to fear the force of gravity, for gravity bends time and time leaches life.

Mistakes are made beyond the wormhole — irreversible mistakes, the consequences of which sneak up on you, even though you know they’re coming. The meticulously-accurate physics of the narrative demand that time become a pitiless foe. It was at this point in the film that I first wept, forced as I was to stare mortality full in the face. This was not the cheap shock of violent death, so commonly appropriated as a means of emotional manipulation, but the acute pain of a loss imposed by separation.

This is a difficult thing to articulate. The emotion tapped by this film is that quiet ache I feel when WALL-E folds his hands in loneliness, when Maximus stumbles drunkenly toward a wine-dark door, and when Frodo departs into the West. It’s an inexorable pain; a profound grief all mortals come to know. That which I had studiously avoided felt suddenly so real, that which I had taken for granted was now precious beyond price. Not since the Ender Quintet had I seen the harsh emotional realities of interstellar travel treated with such sobriety.

The longer Interstellar runs, the more philosophical it becomes. This arises from necessity, as the how and why of its characters’ survival grow increasingly commingled. When confronted with a navigational decision carrying immense opportunity cost, the astronaut daughter of Professor Brand (Anne Hathaway), in love with one of the explorers they’re pursuing, delivers an impassioned plea to her companions regarding the power of love as a guiding force. Of course, since she’s appealing to scientists, Brand posits that love is the shadow of a heretofore-unknown dimension, that it’s explicable by the laws of nature. It’s a self-justification reminiscent of that made by Edward Walker in The Village — and it’s also a serious contention to the viewer. Interstellar is not a film that assumes the world is as it appears.

I feel I am wandering. This story is great not because of its intellectualism, nor because theoretical physicists consulted on its script, nor because it shows off every single cent of its $165 million price tag; no, Interstellar is deep and moving and poignant and powerful because of the way it grips the heart with visceral emotion and pierces the soul with bittersweet beauty. When I watch Cooper grappling for his life in a precipitous wasteland or charging a debris-field in an impossible gambit against incalculable odds, I am caught up not, as I would’ve expected, in his reactionary struggle for survival, but in his quest for transcendence — for a means to defy the limitations of reality and the expectations placed on him by fate. In the uncharted realms he now wanders, survival requires transcendence. He will not go gentle into that good night. He has loved too much to let go now.

This is epic storytelling at its finest, for what keeps me riveted to the screen is neither action nor scenery — not the black holes or mountainous waves or frozen clouds — but a narrative core of human love relationships, written and performed with spellbinding empathy, around which the grand saga of humanity’s fate spirals like a galaxy of light. It is love that drives our heroes, and only love that can lead them home.

Because, Dear Reader, they are their own salvation.

Ah, and now comes the turn. You see, though Interstellar is superior to 2001: A Space Odyssey, it retains a similar hard-core humanism. In a climactic moment, Cooper discovers that it was he who’d knocked a pattern into his daughter’s bookcase, and thus he who’d sent himself on this mission in the first place. Taking advantage of a brief opportunity to transcend the third dimension, he perceives the activity of beings on an even higher plane, reaching back down, as he is, to help him help himself. He surmises that those beings are us, evolved beyond constraints of time, at long last mingled with the splendors we can see.

Not only does this eliminate a supernatural explanation for the film’s uncanny events, it does away with even the standard naturalist cop-out that “aliens did it,” replacing those ideas with pure, unadulterated humanism. But this leap is dependent upon a logically-impossible recursion: only through the help of those in a higher dimension can a human attain a higher dimension in the first place. It’s a past dependent upon a future — the cosmic equivalent of lifting oneself up and carrying oneself away. A sweet lunacy.

Yet what’s the alternative for the committed philosophical naturalist? The answer surrounds us — an endless sweep of pristine desolation, wracked by fits of howling rage or lost in preternatural silences. “Beauty has smiled,” declares Lewis, “but not to welcome us; her face was turned in our direction, but not to see us. We have not been accepted, welcomed, or taken into the dance. We may go when we please, we may stay if we can: ‘Nobody marks us.’” But this is too terrible a thought to contemplate; the silence must be filled, if only by the echoes of one shouting to hear his own voice. That there might be light and life beyond the darkness and silence is but a delusion from childhood. Now is the time to be men! Now is the time to evolve!

This is the great hope of humanism, well-founded in experience. “We must think not as individuals, but as a species,” exhorts Professor Brand, and it’s precisely such an approach that’s enabled our affluent, specialized society to hit an exponential curve of technological advancement over the past century. The more we’re willing to trust one another enough to specialize in only one occupation, the more rapid will be our advancement across the board. Every avenue of knowledge will attract dedicated attention. After all, a theoretical physicist only has the time to theorize because his subsistence needs are already provided for by those who specialize in such things. He is but a single cog in a species-spanning machine moving relentlessly toward transcendence. And, as language barriers fall and globalization takes root, humanity again draws near the point of no return where “nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them” (Gen. 11:6). It’s the great dream of humanism, introduced to the human mind like a blight at the dawn of time — the idea that we can be like God. It’s heady and heroic and corrupt and false.

And it’s the philosophical underpinning of what is now one of my favorite films of all time. Because beauty and emotional resonance transcend intellectual solidity like a wormhole bypassing spacetime.

Yeah, I was waiting for them to say we chose ourselves. Good movie, though the love aspect left me a little dissatisfied. It was like bad philosophy done by scientists. That’s where the movie jumped the shark for me. But it was definitely interesting and worth watching.

I’m curious why you perceived the film’s “love aspect” as “bad philosophy.” Was it because some of the characters attempted to quantify love as a physical dimension? That sounds to me more like a scientific hypothesis than a philosophical assertion.

Love transcends dimensions, as the film claims, only if there are two beings who love one another and happen to be in separate dimensions. Love isn’t a force that binds particles or ripples through space-time. There were some parts of the film’s dialogue, particularly Hathaway’s self-defense of her feelings, that seemed forced in there to connect to the average Joe or Jane in the audience. It was as if the scriptwriters thought, “This film might be too science-y, and moviegoers like stories with heart. Let’s slather on some metaphysical ponderings about love and its place in the universe so people won’t be too weirded out.”

We don’t need to be told how powerful love is, but we also don’t need to be talked down to about what love actually might be. The film’s desperate attempt to explain love in pseudo-scientific terms isn’t surprising though, since God was nowhere to be found in the story, and when you start talking about love on a macro-scale, you have to either bring God into the equation or else relegate the idea to the unknowable “higher dimension” (or explain it in purely practical/social terms as McConnaughey did, which made the most sense considering the movie’s worldview).

Right. The plot’s materialist magic-system required a variable that’d allow Cooper to pinpoint a specific date and location inside three-dimensional spacetime while communicating from inside the tesseract. The only way such a scenario would be viable in a naturalistic model is if love was physically quantifiable — perhaps even the stuff of the fifth dimension. It’s a plot device, pure and simple, though no more ludicrous than the next option when we start talking about higher dimensions (which are, by definition, incomprehensible).

I think it’s unfortunate that the idea of “love” carries so much cheesy, cliched baggage; otherwise, this hand-wave of love into a purely materialistic form would’ve likely come across to most viewers as an intriguing take. False, of course, but not “desperate.” The naturalist has a need to explain love, after all (there being no social utility in affection for the dead, as Brand points out), and I appreciate the honesty of the film for at least not ignoring that dilemma.

Austin:

Wording intentional?

Not an intentional allusion, no, though Screwtape might’ve rejoiced to see Interstellar. Me, I don’t ascribe nearly that kind of seductive power to the film’s pseudoscience. Aside from the fact that a future-dependant past is logically impossible without appealing to parallel universes (Grandfather Paradox, anyone?), the film is, I think, quite transparent about the conjectured nature of everything that occurs beyond the event horizon. In fact, the entire story is science fantasy: we only get within reach of a black hole to study by taking advantage of a wormhole that magically appears, and whose appearance is supposedly dependant on what we do when inside the black hole (and no one knows what’s inside a black hole or if anything is capable of surviving therein). What Interstellar does is to say that if certain convenient and inexplicable things happened, then we, based on our current understanding of physics, might be able to do X, Y, and Z.

While a secularist may well choose to believe in the universe postulated by the film, there’s no possible means whereby such beliefs could be described as “science.” In which case we as Christians are at least back to square one — facing off against self-admitted pagans instead of those still hiding behind a cloak of objectivity-by-association.

Now I’m really intrigued–and at the same time, convinced that my family will never be able to sit through even the first half-hour.

I’m a bit late to this party, but I find it fascinating in this discussion that we’re taking Cooper’s existential realization of “it was me/us all along” at face value; that simply because he discovered how he communicated with his daughter through time, mankind is singularly responsible for all else within the movie. As was pointed out repeatedly throughout the movie, we’re dealing with something on a higher dimension than our own understanding. I actually thought Brand’s peon to love the most singularly explicit representation of God that a godless society could accept: as God is love, and exists outside of the rules of space/time, He is a force to be reckoned with beyond what we can see, feel, or know. As with any other journey we go on in life, I think Cooper’s trip has far more to do with a force beyond his knowledge (and therefore control) than he or even the filmmakers might be prepared to recognize.

And we’ve all seen worse explanations for divinity (I’m looking at you Final Frontier).

It’s good to see you writing another review Austin; I’d love to see more of your thoughts up here at Spec Faith. Coming from the theatrical background I do, I personally focused more on the storycraft rather than the philosophy of the film in my blog’s review, but it was great to read such a thoughtful consideration of the underpinning ideas. I’m certainly looking forward to viewing the film again (and wow, can I just say, I really want that soundtrack).

Thanks Michelle — I try to post a review on SpecFaith at least once a month, but, since reviews have been stacking up of late, you should be seeing more content from me here shortly.

Your point is well taken that the film’s higher-dimensional “beings,” being unobserved, have the potential to be practically anything or anyone — whether future-tense transcendant humans, sufficiently-advanced-technology-is-equivalent-to-magic aliens, or a force of the supernatural, whether the God we know or something else. I chose to take Cooper’s word as gospel regarding the nature of said “beings” because it’s clear that was the filmmakers’ intent. But yes — not only would such beings operate outside the realm of logic, but their nature and even their very existence would be impossible to verify with science. Kinda like God outside of special revelation.

And yeah, the Final Frontier comparison occurred to me as well … *shudder* Say what I might about Interstellar‘s nonsensical philosophical premises, it’s certainly better than that.