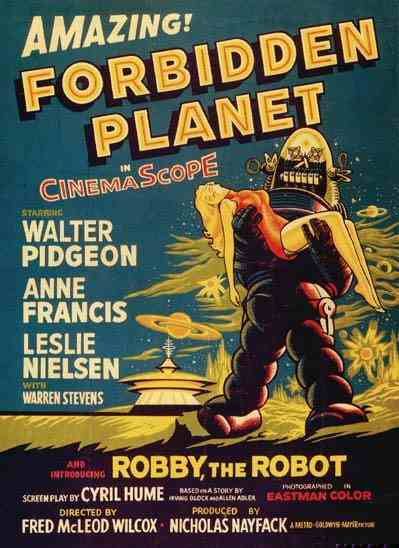

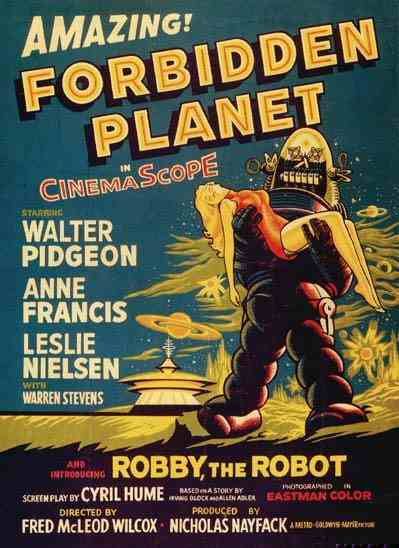

Mind-Blowing Tech Is No Match For Monster In ‘Forbidden Planet’

Forbidden Planet is special for many reasons.1 It’s the first science fiction film to show humans traveling in a starship of their own making to an interstellar world far from Earth. It marks the cinematic debut of Robby the Robot, who went on to enjoy a rich film and television career and even has his own IMDb page, and stars a young Leslie Nielsen in a serious role as a rational and believable leading man. Considered one of the great science fiction films of the 1950s, it had a huge influence on later science fiction, particularly Star Trek. The story is well crafted and richly layered, exploring humanity’s potential for both intellectual achievement and sinful degradation. Besides all that, it’s wonderfully entertaining, with beautiful special effects, solid acting, and a clever, thoughtful script.

The film came out in 1956, smack-dab in the middle of a decade when science fiction was growing in popularity as space travel began to look really achievable. It was an optimistic time, but with an undercurrent of anxiety. Wages were high, but the arms race kept people on edge; school children practiced “duck and cover” drills in case of nuclear bombing. While Americans loved their technology and the prosperity it made possible, they also feared its potential for destruction. This ambivalence provides much of the tension in Forbidden Planet.

The film came out in 1956, smack-dab in the middle of a decade when science fiction was growing in popularity as space travel began to look really achievable. It was an optimistic time, but with an undercurrent of anxiety. Wages were high, but the arms race kept people on edge; school children practiced “duck and cover” drills in case of nuclear bombing. While Americans loved their technology and the prosperity it made possible, they also feared its potential for destruction. This ambivalence provides much of the tension in Forbidden Planet.

The film is often compared to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and there are striking similarities between the two. A man with secrets, grudges, and mysterious powers—a magician of sorts—is marooned on a strange world with a daughter who’s been raised in such profound isolation that the sight of any man other than her father is cause for marvel. They have two servants—one good and reliable, non-human but anthropomorphic, and another of questionable origin, a violent savage not above murder. And when visitors arrive from the magician’s world of origin, things quickly hit the fan.

The film opens with Commander Adams and crew coming to Altair 4 to check on some colonists who settled there twenty years earlier and haven’t been heard from since. While his ship is still in the atmosphere, Adams is contacted by someone on the planet who tells him everything’s perfectly all right now, we’re fine, we’re all fine here now, thank you, so just move along. When Adams refuses to abandon his mission, his contact on the planet grudgingly permits the ship to land but says he won’t be answerable for the safety of ship or crew.

The contact turns out to be Dr. Edward Morbius. He’s a philologist, a specialist in language and linguistics—no doubt a useful person to have in a party of space colonists, but not one you’d expect to thrive alone on a hostile alien world. Morbius is the sole survivor of the original party. All the others—except his wife, who died later of natural causes—were mysteriously and violently killed by an invisible being not long after arrival, and Morbius fears that Adams’s crew will suffer the same fate. Morbius himself, and his daughter Alta, are “immune” to the creature’s rage.

The name Morbius suggests the Latin “morbus,” meaning mental illness; it was later reused for an unstable renegade Time Lord in an episode of Doctor Who. It’s an apt enough name in Dr. Morbius’s case. Dressed in black from head to toe, sporting a widow’s peak and a neatly trimmed beard, living on a fortified extraterrestrial compound with mind-blowing technology, a robot servant, and a free-roaming tiger, the guy is bound to have some supervillain tendencies at the very least.

Robby the Robot, played by himself, is a delightful character with a dry wit, a plodding gait, and a talent for replicating things at a molecular level. He appears to be programmed with at least the first two of Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics: he will not harm a human, and he obeys all his master’s commands except when doing so would violate the first law. When the two do come into conflict—when obeying a command would harm a human—the dilemma sends Robby into a temporary electro-sizzling paralysis.

Both Morbius and Prospero have a second, less tractable servant. In The Tempest, it’s Caliban; in Forbidden Planet, it’s a mysterious, deadly presence, referred to at first as the Planetary Force and later as the Monster. In both film and play, there is some question as to just what this troublesome being is. Caliban is in fact a man, though a coarse and unwashed one, but characters who see him for the first time always express some doubt. He is so weird-looking and bad-smelling that humanity doesn’t want to claim him. Like the Monster, he’s driven by primitive and violent impulses beyond his own comprehension.

In both stories, the master-servant relationship is uneasy, even torturous. Both Caliban and the Monster are referred to as devilish in origin; both are closely associated with dreams. Both have masters who would like them to just go away. At one point Morbius cries out in anguish to the Monster, “Stop! No further! I deny you! I give you up!” But giving it up is easier said than done. Morbius can’t just renounce the darkness and make it go away. It’s as systemic to him as sin itself.

Morbius’s compound sits above an underground laboratory built by the planet’s former inhabitants, the now-extinct Krell. Before their mysterious disappearance, the Krell developed a machine capable of harnessing the imagination to make material projections. It was an incredible intellectual achievement, but exacted a terrible cost. (Imagine a tangible demonstration of Luke 6:45.)

In 1 Corinthians 1, Paul says that wisdom can’t save us. Wisdom is an excellent and praiseworthy thing, as the Bible makes clear elsewhere, but we don’t have all the wisdom, and our sin makes us incapable of properly exercising whatever wisdom we have. It is only power that can save us — Christ’s power over sin.

Often we pretend that knowledge is the only issue. When speaking of someone who is smart but morally compromised, we often add, “Well, I guess he isn’t that smart” — as if it’s only lack of information or comprehension that makes people behave badly, and smart people are never selfish or violent or perverse. We speak euphemistically of “bad decisions” rather than sin. We don’t want to acknowledge that our problem is deeper than ignorance; we want to believe that pure pragmatism can govern our behavior, molding it into something benign and harmless that will never bother anyone. But even if we could be governed that way, we wouldn’t want to, not really. Not making waves, not getting into trouble, isn’t enough for us. We want the twisted excitement of the forbidden. Bland security is boring, a sated inactivity where our darkest impulses are not satisfied.

Who among us doesn’t have something evil lurking in the heart, waiting for the right opportunity to be brought forth? And if the power existed to give physical form to everything the mind could imagine, who wouldn’t have just cause for fear?

Forbidden Planet addresses these questions deftly and thoughtfully, without ever bogging down or getting too heavy. The issue that so preoccupied American society in the 1950s — man’s uneasy relationship with technology — turns out to be a portal to something even more terrifying: man’s relationship with himself.