‘Jesus Triumphant’ … and Hollywoodized

Saying that the penultimate volume in Brian Godawa’s Chronicles of the Nephilim series bites off more than it can chew paints a rather inadequate picture.

To do justice to Jesus Triumphant, the metaphor requires extension. It’s more like the novel chomps down on the leg of a live lion, hangs gamely on for a bit whilst being whipped through the air, then gets flung off into a nearby bog, where it slowly sinks to its doom amidst the skeletons of extinct cliches.

An overly harsh assessment? Well, that depends. If you enjoy watching characters laugh for pages at their own unfunny jokes, if you think it’s even faintly realistic for archangels to bicker like incessantly petulant children, if you think it’s high time someone unveiled the nephilim behind every demon behind every bush, or if you’ve always wished that the gospel story climaxed not with Jesus’ resurrection, but with an underground melee between pagan gods and resurrected patriarchs, then this is the book for you.

Normally I wouldn’t judge a novel for featuring speculative elements. I love fantasy, after all. But when a secret-history story uses the life of Christ as fodder for its fancy, and especially when it follows that up with an appendix purporting to portray its plausibility, I have a bone to pick.

I might as well start with the substantial stuff. Spoilers, obviously, are about to abound. One of the central conceits of the story is that Jesus’ earthly ministry was largely preoccupied with “dispossessing” the “gods of the land” — the fallen Watchers of the Heavenly Council, among whom Satan is a mere peer. This milieu should be familiar to readers of previous novels in the series. What disturbs me this time around is the manner in which this speculative narrative — derived from the apocryphal Book of Enoch — becomes an interpretive lens by which the entire gospel is distorted.

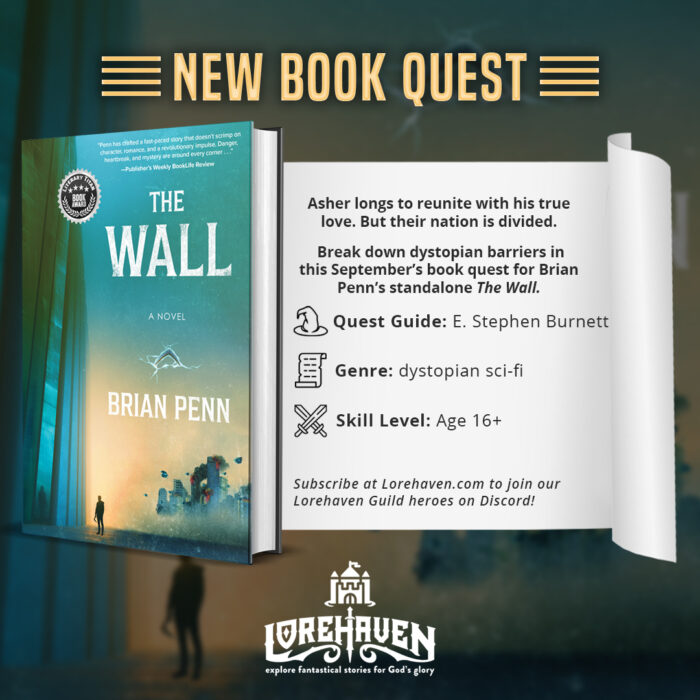

Some familiar imagery to put you at ease …

I didn’t react this way when Godawa reconstituted the Old Testament. Perhaps that’s because I feel less of a personal connection to Enoch and King David, or perhaps it’s because their stories don’t carry the vast spiritual implications borne by the story of Christ. Either way, the Jesus of Jesus Triumphant does strange things, and he does them for strange reasons. Though Ephesians 6:12 tells us that we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places, the premise of Jesus Triumphant is that this verse is true only because Jesus, along with a team of special-forces angels, spent his time on earth literally wrestling the “heavenly flesh” of the gods so we wouldn’t have to.

When Jesus goes to Tyre, it’s to imprison the goddess Asherah. When he goes to Caesarea Philippi, it’s to defeat the Greek god Pan. When he goes to Jerusalem, it’s to throw down the “mole-god” Moloch. Oddly, though, Jesus has his angelic bodyguard perform nearly all of the dirty work — he leads them to the lair, then stands around looking all mysterious while they break and enter. The utility of his presence is unclear at best, and if, as he claims, he’s “binding the strong man” of Mark 3:27, he certainly seems to delight in delegating the sweaty stuff. Oh sure, he does call down fire from heaven to torch an enemy stronghold. But that’s after he’s already sent in the ground troops. Sooo … even worse.

I was prepared to like this book going in, because I thought it capable of turning the corner from the brute-force tactical heroism featured in its predecessor, David Ascendant, to the strategic subversion pulled off by Christ on the cross. I thought the reader might’ve be treated to a clever misdirection: “You expected a conquering king? Say hello to the suffering servant.” But it was not to be. In the “biblical cosmic war of the seed,” there’s nothing quite so clear as the fact that it was Jesus’ ultimate humiliation which precipitated and enabled his total victory. In this novel, however, Christ’s sacrificial death and resurrection seem almost incidental when compared to his skills with a whip-sword, or his ability to ride Leviathan in a Galilean storm (yeah, you guessed it: he wasn’t really walking on water … isn’t this version cooler?!).

That’s not to say the spiritual mechanics of propitiation are neglected. No, they’re there alright — described in excruciating detail by Simon the Zealot, depicted as a former initiate of the Essene community at Qumran. Whatever sense of mystery and wonder might’ve attached itself to Jesus’ actions is regularly deflated by Simon, who regales a dewy-eyed Mary Magdalene with partial-preterist polemics in response to even the tiniest plot developments. Mary herself — having recently renounced the fully-nude-temptress business after Jesus expended a troubling amount of effort exorcising seven demons from her — provides the perfect foil for Simon’s erudite extemporizations. She’s smarter than him (even Jesus says so!), yet still demure, simpering affectionately at the disciple’s attentions. Their dynamic might’ve been cute, if it didn’t totally ignore the psychological trauma one assumes she must’ve endured as a pagan priestess in the cavern of Pan. Oh well! Off with the old, on with the new! That’s par for the course in this story: internal human sin takes a backseat to external demonic influence.

And, speaking of demons, you may be surprised to learn there’s really no such thing. What there are, according to Godawa, are the disembodied spirits of deceased nephilim. What’s that you say? You saw this coming ten miles away? Yeah … me too. Moving right along.

So Jesus dies on the cross, right? And then he descends into Hades, right? Stop me if you’ve heard this one. So then Jesus journeys across the Ancient Near East through a subterranean netherworld reminiscent of a level in Super Mario Bros, right? Oh, you have heard this one before? So you know that after he passes the hordes of zombies and parts the river of fire, he shows up at Abraham’s Bosom to conscript every single hero featured previously in The Chronicles of the Nephilim for his upcoming battle with the assembled pantheons of Greece, Egypt, India, and the Northlands? It’s the Great Patriarch Reunion, the most cringeworthy curtain-call of all time!

Oh, sorry — that was the punchline. You mean you really hadn’t heard that one before?

In case you’re still wondering what’s not to like about this Hollywoodization of the gospel, I must appeal to the effects of emphasis. The irony of making Jesus’ first coming largely about physical conquest is that it effectively diminishes Christ’s power. If the devil wasn’t rendered impotent the instant Jesus rose — if in order to complete his unfinished redemptive work Jesus then had to beat Belial in hand-to-hand combat — his titular triumph is demoted from an issue of right, of authority, to a mere matter of muscle.

Of course, this is all delivered to us through a partial-preterist paradigm, so we’re supposed to believe that Jesus’ post-resurrection detainment of Satan was the fulfillment of Revelation 12, and that the remainder of John’s prophecies were fulfilled by A.D. 70. This lends events a kind of sense, but also demonstrates why I, personally, harbor distaste for preterism: it reduces what’s most vast and epic about New Testament eschatology to a handful of relatively small-scale, localized, clandestine affairs observed and remembered by few. That’s my bias speaking, admittedly, but I think this matters beyond my mind. It’s flat-out weird for the savior of mankind to spend his last days on earth conducting a secret raid on a hidden bunker full of drunken deities. All other interpretive traditions also believe that Jesus will eventually pummel Satan into submission, of course, but the way in which Jesus Triumphant bundles that event with Christ’s resurrection blurs the eschatological lines, making it impossible to tell which action had what spiritual effect.

Another consequence of the novel’s emphasis on angelic warfare is the way in which actual human beings seem to fade into the stonework. When so much of the emphasis gets placed on gods and monsters, ordinary people and the sin that plagues them begin to feel relatively inconsequential. What’s ironic about this is that the actual incarnation of Christ had the opposite effect: when God took on flesh he elevated, dignified, honored, and ennobled the entire human race just by association. But in a world where the “gods” have been taking on flesh since before the Flood, somehow the physical presence of Jesus just doesn’t seem all that special, especially when he spends most of his time bagging them like trophies.

So that was the substantial stuff. Onward, to style!

I’ve not much to say here, honestly. This novel features, as per usual, an overabundance of modifiers clogging the drain of its narrative flow, as well as an inexplicable fixation on the words “serpentine” and “preternatural.” There’s scant immediacy of description; the action, consequently, feels rote and contrived. And, as long as we’re on the subject of description, the tonal depictions of good and evil are about as subtle as anything in an animated Disney flick. Stereotypes abound. Ba’al, Asherah, and Moloch, our favorite fallen gods, get their by-now-requisite scene of mutual ogling — as stale as the laundry-list of dishes at any Redwall feast. I get that evil’s being portrayed as childish, but the presentation’s garnished with such unselfconscious solemnity that I end up gagging at the story itself instead of the characters in it. It’s unclear to me why Belial isn’t described as mustachioed, since he’s certainly twirling something throughout his introductory “temptation” of Jesus:

Make-up accented serpentine eyes that melded beauty and malevolence. This being was confusion and chaos incarnate. It stared down at [Jesus] with cool contempt.

As I recall, “temptation” is supposed to mean “a thing or course of action that attracts or tempts someone.” If a thing inspires only revulsion, it can’t, by definition, be tempting. But “serpentine,” apparently, is the most seductive word in the English language. In Jesus Triumphant, evil always feels suuuper evil, and good … well, as exemplified by our favorite archangels, good just seems stupid, and childish, too. Example:

“He could get hurt,” said Mikael.

“Not if you do your job,” said Jesus. “Uriel, why don’t you watch over him for me.”

“Jeeeesuuuus,” whined Uriel. “Why always me?”

Gabriel teased, “Because you’re small enough not to intimidate a human.”

Uriel was the smallest angel of the lot, a full foot smaller than most. But he made up for it with his wits and will power. No one could match his double swords in speed or technique or his mighty tongue. “But Gabriel, you are more homely and plain looking, so you won’t scare him either.”

Jesus said, “Uriel, stop whining. Did I not have you watch over Noah?”

“Well, yes, but…”

“Was he not the first of my chosen line to protect?”

“Yes.” Uriel felt like a scolded teenager. “But he was a grump at first. You have to admit.”

Jesus said, “The greatest among you shall be your servant.”

Gabriel added, “Unless you become like a little child—with the emphasis on little—and child.”

Jesus said, “Shut up, Gabriel.”

Anyway, enough about that. Let’s talk humor! Boy, is there a lot of it.

“So there I was, staring up at this big oaf, with his long Anakim neck swaggering about like a taunting cobra.” Caleb swayed his neck to show them. It was a bit funny, so the men around the fire laughed.

Ha. Ha.

“We will find Simon for you,” said Demas. “But first, we need to bathe. We stink like excrement.” The men around laughed.

Ha. Ha. Ha.

Methuselah changed the subject, shouting out, “I don’t know about the rest of you warriors, but this resurrection evidently didn’t take away my earthly hunger. I’m famished, let us eat!”

The men and women laughed and made their way back to camp.

Whoo-whee! Them there’s some real knee-slappers! It’s too bad we have to move on.

Fortunately, I get to conclude with what I liked about this novel: mainly the manner in which the cast at the foot of Christ’s cross — the Roman centurion who confesses Christ’s deity, the criminals crucified on his right and on his left — are introduced early and separately as the story’s most distinctive and multifaceted characters. Theirs is a subplot I don’t want to spoil, so I beg leave to omit even their names. Suffice it to say that through the experiences of these three we explore loss, fealty, hope, justice, deception, betrayal, despair, and redemption. Though it’s narratively necessary for their tales to intertwine with that of Jesus, I wish they hadn’t. That’s a terrible thing to say on multiple levels, but it’s true. No characters with the potential they exhibited deserve to be subsumed by the weirdness that is Jesus Triumphant.

I have to say, I haven’t read these books and have no intention of doing so, but I always tune in for your reviews because I get so many LOLz. 😀 Thanks for the morning amusement! (And I’m sickened by how this book apparently portrays my Savior. Ick.)

“What there are, according to Godawa, are the disembodied spirits of deceased nephilim.”

That just means Brian had been reading Chuck Missler. I don’t know if this theory was around before Chuck, but he’s certainly one of the more well-known supporters of it.

Also, don’t you dare use Redwall in a put down!

I crossed a line there, didn’t I?

hollars at the heavens

I’m sorry, I take it back! Tell me again about the turnip-‘n-tater-‘n-beetroot-pie! Tell me again of its gurtness! I want to knoooow!

“I was prepared to like this book going in, because I thought it capable of turning the corner from the brute-force tactical heroism featured in its predecessor, David Ascendant, to the strategic subversion pulled off by Christ on the cross.”

You read Enoch Primordial, so why would you ever think that? I really thought I had purchased a screenplay by mistake.

I don’t care how Godawa uses the Bible, as long as he connects everything he changes. Heathen me. I think everyone’ s afraid to touch the character of Jesus, so he always stays boring. We’re all secretly insecure because we have to make Him better and more amazing with insight into how divine He was, OR we risk feeling less inspired to faith by Jesus, as in the person he was on earth. The one without the glowing blue eyes and supernatural entourage and obvious signs of heavenly royalty.

Somehow, Godawa turns him into an action figure. It coulda been an improvement, but from what you’re saying it’s not.

How can someone with such a great idea tell such an unimaginative story?

I guess in some ways Jesus is the great untouchable character … if he’s left in this world. He is the Word of God, after all, and one must be very careful when putting words in his mouth, especially if one takes great pains, as Godawa does, to present one’s story as plausible. But transplant Jesus into a fantasy realm and everything becomes easier. Lewis’ Aslan and Dekker’s Justin testify to this fact. Setting the story in a constructed world allows the writer to give his allegorical messiah an actual personality without constantly rubbernecking for heresy. There’s plausible deniability, a necessary layer of distortion. We know the writer isn’t trying to say that Jesus is exactly like the allegory, which is why it can become more than a mere allegory.

But this story … I dunno. It could’ve felt real. The characters could’ve been rounded out, the description amplified, the dialog improved, the sentiment earned. But those are all matters of craft and pacing. I’m not sure I’d be able to stomach this Jesus even if he spoke with Rothfussian eloquence.

I’ve only read Enoch Primordiol. Sounds like insight into ethics was missing from the author’s conception of Jesus the Character. Or maybe it was defined so loosely and did not matter to Godawa. How Jesus’ actions ethically measured up. What kind of demon blood spilling fest this was. What kind of fight you fight ultimately makes the fighter who he is.

I get the feel that this whole series was a little vapid. Like everyone in it was created by a manically stereotyping casting agent to titilate (erotically and otherwise). Plus there’s the sensationalism of trauma, sex and violence (plied for all it’s worth to keep the reader interested) but none of the human psychological impact is explored beneath the surface- lest it stop the plot from sweeping along in “Gladiator” fashion. Unfortunately, none of the respect for real consequences and problems that are experienced in life (and in fiction), is retained in the process. It is sacrificed to the adventure story you read, which leads ultimately to the adventure story cheapening YOU…..Am I close?

Bulls-eye. Quite precise.

Amazon has a majority of positive reviews stating how amazing this book is.

I’d like to email you but I have no idea how to do it.

Yes, yes you did. 😀 That’s my childhood you’re talking about right there, with all its tasty repetition. I even found recipes online from all those overdone descriptions, and made some of those dishes.

Joanna,

I haven’t read these books (and after this review, I never will) but I can tell you tha the “demons are disembodied Nephilim” theory is actually really old, and not only predates Chuck Missler but even predates the New Testament. This theory is in the book of Enoch, certain aspects of which are alluded to in James and 2 Peter, as well as some of the early church writers such as St. Justin Martyr in the 2nd century.

This is not to say that the theory is true. To me the “fallen angels” theory makes a lot more biblical sense. But even if the idea is kind of lame, it’s worth pointing out that it’s a very OLD lame idea, not some modern innovation.

Seems like the kind of story that trying to shoehorn popular ideas of “spiritual warfare” into biblical stories that don’t contain it.

Why don’t we just make more media about the goriest OT stories (Ehud, Jael, basically any of the judges)? Just, go over there and watch the 300 ripoff with biblical trappings, bro-dawgs. We’ll all be a lot happier.

There’s not much you can do with this subgenre without going weird, or going bland. At least Godawa sounds readable, even if it’s high camp. There’s a ton of spiritually correct, respectful books about Biblical times, and they are perfect to fall asleep reading by.

More an argument to avoid Biblical times fiction at all, I think. Too tightly constrained to speculate.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say one should “avoid Biblical times fiction at all.”

After all, one of my favorite underappreciated fantasy series was by an author dubbed Douglas Hirt, who wrote a surprisingly classy and in-depth yet “pulpy”-feeling series called The Cradleland Chronicles. Since then I’ve seen plenty of fantasy authors take on this genre–which I could call pre-flood fiction–but Hirt’s trilogy seems the most solid yet fun approach to the idea. He even went so far as to include Nephilim, genetic experiments, and Peretti-like angel/demon warfare. He also included highly speculative yet not-at-all-unbiblical concepts such as Eve surviving to the era of Lamech (Noah’s father), Noah receiving training from a theophany-appearing Christ in the Garden of Eden (before it was removed from Earth), and a Satanic colony on the fifth planet (which of course was vanquished during the Flood). Not kidding.

But throughout all this the “simple” Gospel was honored and God glorified.

I have not been able to read Godawa’s fiction. But in general — and perhaps inconsistently, given my enjoyment of “Cradleland” — I’m opposed to going down the “Nephilim” rabbit hole. It seems a theological drug trip, akin to Lewis’s warning about the devil that people can believe in him yet develop an excessive and unhealthful interest in them. I would not say that about Godawa, for sure. But I have seen it in other people, who seem to conclude the only thing worth knowing about from the Bible are things about “the antichrist” and demons and Nephilim. In other words, they ignore Jesus/Gospel and want to scavenge Scripture for parts to build a haunted house.

As I mentioned a few years ago in Just Reached My Fill of ‘Nephilim’:

Sounds like just another flavor of weird. I like weird, but not many people do and Christians tend to get angry about any weirdness even close to the Biblical narrative. The idea of Nephilim was to somehow create a theological justification to be weird, because the audience rarely would read tradiditional weird SF or fantasy. But put the Bible on it…(or in this case the Book of Enoch.)

You’d think that … but then you get to the end of the book and realize that the author’s still talking, and that he’s telling you about obscure historical connections and underappreciated sources and neglected interpretations and etymological curios and … and you realize that none of it seems weird to him. None of it at all.

Oh, yeah you get people who also believe it too. Geek expressions in Christianity tend to stuff like that, or the 4 blood moons, or various errata and heresy.

If biblical fiction is bland, it’s because Christian authors are cowardly. There’s plenty of kindling for a rip-roarin’ tale of darring-do set in Biblical times, but it requires a strong stomach to set it alight — something not terribly common in evangelicalism today. I thought ‘David Ascendant’ was better than ‘Jesus Triumphant,’ partly because it endowed most of its cast with a dark side. But that approach doesn’t work with Jesus, and never will. “Biblical fiction” encompasses much more than “Jesus fiction.”

They’ve had 60 plus years of trying, starting with Ben Hur. It doesn’t seem to me to be a genre you can do a lot of rip roar with. I guess it doesn’t help that when publishers think Biblical fiction, they see Brock and Bodie thorne romances.

Actually, Ben-Hur the book was written in 1880.

EIGHTEEN. EIGHTY.

By a former Civil War general.

Charlton Heston just made its last pop-culture impression 60+ years ago.

I think I need to go look at kitty pics now.

So… It’s Jesus meets the Justice League co-starring the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles as the Archangels? Uriel=Michelangelo