Travis P here. After a lengthy departure from the Guide to War that Travis C and I are working on, Iâm picking up our subject again with more on the topic of training. The next two posts will break down some training issues that relate to professional armies (because barbarian armies train, but not systematically in the way as pros do). This week will look at the training of âCombat Armsâ–that is, the instruction required for people who handle weapons that directly or indirectly kill enemies. This training has been throughout history in general organized by weapon type, by system of transportation combined with a weapon, and to a degree, by the philosophy of how to use them–otherwise known as âmilitary doctrine.â

This kind of training has gone through a variety of transformations over time, based on general types of weapons systems, transportation systems, and military doctrine in use. These historical patterns demonstrate models that can apply to fictional worlds.

First, letâs discuss historical transformations a bit. The city-states of ancient Sumer were the first nations to use their agricultural surpluses to hire full-time, trained soldiers. At first, all their soldiers fought on foot, but from the very beginning of trained armies, they differentiated according to weapon type, some carrying spears, some with battle axes, some with daggers (all wearing long cloaks and copper helmets for armor) and some using slings or bows. (See link on the Sumerian military for ancient artwork and more info.)

But soon, the Sumerians learned to put armed men in four-wheeled wagons drawn by either horses or donkeys, and also put armed men on river boats, linking weapons with types of transportation for the first time. The arms used with the transportation at first were of the same type used on land–axes, daggers, spears, and bows. At first, the fighters in the back of the wagons or boats probably had the exact same training as those who fought on the ground. But using them off a new platform created new challenges and eventually spurred the development of new training.

Ancient Roman versus modern Italian infantry.

Credit: Youtube.com

At even the most basic level, a military will have infantry soldiers, human beings walking into combat, with at least several basic types of weapons, including weapons designed to kill at a distance weapons and weapons designed to kill up close (i.e. âmelee weaponsâ). (Spears and throwing axes and a few other weapons can be effective both up close and from a bit of distance). Infantry soldiers may hitch rides from various vehicles (which requires at least a bit distinctive vehicle training), but if they fight on their own feet, they are still considered infantry. Even if they carry modern, computerized weapons, they are in the same category as a Sumerian in a long cloak and a copper helmet, sporting a bronze-tipped spear. Infantry, when given the opportunity to seek shelter and fortify, are the best at conducting defense. Infantry can fortify towers, hills, and other strong points or create new strong points by digging trenches, or foxholes, or throwing up barriers. Though in the open, infantry are vulnerable to cavalry attacks.

But most militaries in the history of the world have incorporated some sort of fighting attached to a transportation system into their military. Whether by wagon, by chariot, on horseback, or (in modern times) in lightly armored vehicles, these faster-moving soldiers have had tactics in common from Sumerian times to the present. These tactics include scouting ahead of the infantry, attacking enemies in the rear (or their supplies), or attacking as shock troops to crush the morale of the main body of enemy forces. This branch of the military, of course, is the cavalry. Cavalry units are generally much better at attack (and scouting) than they are at defense.

Naval forces have shared a great deal in common with cavalry units in their tactics, but not long after naval forces came into use, the ship itself was used as a weapons system–ramming into enemies–in a way real horses are usually reluctant to do. Naval ships probably rammed one another long before they developed special devices helping them do so (like those of a Roman trireme). In so doing they pioneered a different kind of weapon, a crew-served weapon, one that requires more than one person to operate. Navy forces have also had their own type of Infantry that are trained to operate on and off ships–marine infantry, or in the United States, simply the Marines. In certain times and places, marine infantry were nothing more than regular infantry put on a ship, but there are advantages to training marines a bit differently–if nothing else, they need to know how to swim.

Roman Trireme with drawbridge to help marine infantry and a ship-sinking ram.

Credit: Romae-vitam.com

Boarding ships with marines or aggressive sailors is one way to destroy an enemy ship, but navies have always sought other shipboard weapons to destroy enemy vessels. Rams became fire weapons and fire weapons became cannons and those in turn led to torpedoes and missiles. Many naval weapons fall in the category of high end capability weapons as discussed in the last post, but not all do. Deck guns are not necessarily that advanced, even when they require a special crew to serve them.

What started with naval weapons crossed over to the land. Ancient armies first discovered that their calvary-type units, so effective against infantry out in the open, proved to be nearly worthless against fortified infantry. While an overwhelmingly superior number of infantry usually can take a position only held by infantry, itâs very difficult and bloody. Crew-served weapons on land, siege weapons or engines, were invented to break through strongholds. Siege weapons early on included towers Mesopotamian engineers assembled, catapults, and giant stationary crossbows called ballista. Siege weapons would eventually lead to the development of artillery, the third major branch of ground force combat arms, after infantry and cavalry.

In Roman times the ballista was the most common kind of artillery, serving the basic purpose of extending the range of Roman troops to strike individual enemies through directly firing at them. Catapults, which the Romans also knew about, hurled rocks over walls in high arcs (as did the slingers in ancient Assyrian armies) into besieged cities or camps, indiscriminately killing or injuring anyone who happened to be where the rocks fell, causing enemy casualties by indirect fire.

The artillery branch of the military consists exclusively of crew-served weapons, weapons that require training for a group of operators to be able to function, but which may not represent high end capabilities, depending on the nation that owns them. Once the artillery branch gained cannons, the two basic roles of direct and indirect fire remained important. Direct fire was mostly used against fortifications (and in the navy, against enemy ships), and is responsible for the fact castles are no longer effective in warfare, while indirect fire was lobbed in various ways into mass formations of enemy or locations enemy might be. Today, artillery is mostly concerned with indirect fire, but has systems that are capable of direct fire (especially guided rockets and missiles).

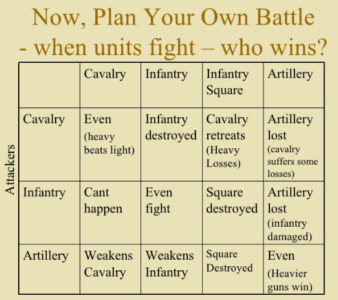

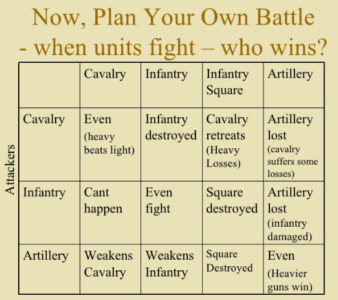

Table showing different types of units fighting each other in Napoleonic Wars. Credit: Slideshare.net/MrJ

The three main branches of ground forces: infantry, cavalry, and artillery (if we allow artillery to include siege weapons), dominated all battlefields everywhere in the world in almost all professional armies, from the time of the Sumerians up until the 20th Century, in particular in the Napoleonic Wars. The 20th Century saw the development of what we could perhaps think of as land ships–vehicles with armor like ships that can move over terrain, with weapons integrated into the structure of the vehicle itself. These weapons, otherwise known as tanks, form their own distinctive military branch, armor.

I earlier commented that military doctrine (or the concepts or philosophy behind the use of weapons) affects training as much as the particular weapon warriors train for and as much as the transportation system attached to weapons use. I’m only going to illustrate that point here, with a comment on military doctrine as it affected the training for tanks.

Tanks were first designed to cross trenches in World War I under enemy artillery and machine gun fire–in effect, their original purpose was to breach a specific kind of infantry defense. Later, between the world wars, the British in particular developed slow-moving tanks with the purpose of supporting infantry and faster-moving tanks with the purpose of taking over some of the roles of historic cavalry units. Military doctrine affected both the design of weapons and their use. But note that Blitzkrieg, the German doctrine of using armor units to first punch through strong defenses alongside infantry the way the first tanks did, then to rush behind enemy lines to cut off enemy formations from their supply chain, the way cavalry units historically did, made tanks much more effective beyond whatever design advantages German tanks may have had. In fact, the French tanks of the early forties are generally considered as suitable for Blitzkrieg as the German tanks were, or even more so–yet since using tanks that way was not part of French military doctrine (they felt tanks should be distributed among the infantry to help them defend themselves when in the open), French tank crews were not trained on how to conduct Blitzkrieg. So they didn’t use their armor that way–much to their disadvantage.

French Char B1, nemesis of German tanks (but poorly employed). Credit: tanks-encyclopedia.com

Note that armor as a military branch happened at the same time as another branch, military aviation, which both supported ground troops and in specialized formations, supported naval units (and later took on the role of fighting other air units). Modern combat arms to this day include infantry (including elite infantry, i.e. special operations forces), cavalry, armor, artillery (including artillery designed to attack aircraft), and military aviation. And of course each of these branches also exist to a certain degree within navies, including marine infantry, elite marine infantry, fast small ships like cavalry, large heavy-hitting ships that are a bit like armor and artillery rolled into one, and of course naval aviation. Each particular specialty in combat arms having its own distinctive training.

Ground attack from space.

Credit: Klaus WIttmann via ArtStation.com

While the names will change, we can expect futuristic militaries, say space-based ones, to have multiple branches that run in parallel with military organizations and systems we already know. Starships designed to fire weapons at planets or lob indirect weapons into regions of space will functionally be like artillery, even if thatâs not what they will be called. Fast moving formations of spaceships like cavalry will still be needed–shipboard infantry will probably be needed, as well as ground assault forces. The equivalent of an air force would be landing craft able to operate in planetary atmospheres, passing through the air as a bridge between space and ground.

A dragon attacking the ground in Game of Thrones.

Credit: LA Times

Fantasy militaries can meet the needs of different branches of combat arms in different ways. Dragons could combine the capabilities of air forces and artillery. Mer-people could form a distinctive branch of underwater marine infantry. Magic could provide indirect fire weapons. Etc.

The point for this post though is that unless you write a story that portrays a society so futuristic that knowledge is directly downloaded into military members (or a society with powerful magic able to do the same thing), each one of these fighting military specialties will include its own training, which is quite distinct from other kinds. Each type of training requires time, which means that any one character can probably only master one type of fighting, or perhaps two–but not everything (a possible exception to this might be found in elves or other species that live very long lives–but even elves would have reasons to specialize in particular weapons, lest they fall behind the skill level of other near-immortals who chose to specialize).

For cavalry and other military branches for which a transportation system of some kind is key, knowledge of that system, be it the back of a horse, a chariot, a dragon, a ship, or a fighter plane, is probably the most important element of training. Knights and samurai spend a lot of time with horses–fighter pilots need to spend a lot of time in the air–sailors develop their skills over prolonged periods at sea. Thereâs an enormous difference in the capabilities of well-trained, seasoned veterans than newbies who are fresh to the fight.

For artillery and similar forces that rely on technical skills, their training embraces a wide variety of things that are not directly dangerous to the enemy, including maintenance of weapons, their operation–even the mathematics required to accurately lob an artillery shell. (In this regard, artillery and related weapons skills is most like the high-end capabilities training we discussed in the last post).

Infantry troops, the most basic element of the vast majority of all militaries in world history, though they may someday be supplanted by combat robots or something similar, are the ones that most require the kinds of battle hardening and psychological conditioning that weâve discussed in previous posts. But they also require training in their weapons systems, how to operate them, how to use them even under stress, and note that infantry weapons training does include crew-served weapons, especially machine guns and mortars (which are really like small artillery).

Note that the training required for combat arms introduces the concept of combat arms itself. While we will say more about combat arms operations in future installments, for next week we’ll discuss those types of skills that militaries train for that support combat without directly killing enemies, like medical and maintenance specialties.Â

Travis C here with a rather sideways example of the distinctions weâre discussing with combat arms. Weâll introduce another related term, combined arms, in future posts. Combat arms is a way to describe the individual components of the military forces within your world-building. Combined arms describes a military philosophy of âcombiningâ two or more of those functions in a way that the enemy cannot effectively defend against one without exposing itself to the strength of another. Also distinct from supporting arms, when two or more of the combat arms support each other in a mutual manner but can be defended against jointly (think of soldiers under their shields as a defense against either arrows or rocks – supporting arms, versus cavalry and archers working together that shields alone might not withstand – combined arms). Before we get to that complexity we need to understand the individual components well enough to describe their strengths, weaknesses, and how they developed into a cohesive force through training.

I feel confident we all have a series of books, TV series, and movies that depict the traditional categories of combat arms Travis P described earlier. Whether itâs battalions of orc infantry in formation on the Pelennor fields, the Rohirrim cavalry charging down the slopes outside of Helmâs Deep, the great mobile engines of the Telmarines, the dragons of A Song of Ice and Fire, or the vessels of the fleets of the Empire, the Rebel Alliance, or the Federation, we have many examples that clearly align with our conceptions of these combat arms categories. The fact they exist is clearly shown, though all too often we miss out on the reality of how such units are trained. We only see the great, climactic battle-to-save-the world, and not as often the training that occurred before hand.

As much as I hate to reuse an example, Brandon Sanderson really hit this nail on the head with his Stormlight Archive series and the plotline of Kaladin Stormblessed.

Kaladin Stormblessed

Image credit: Alex Allen via Stormlightarchive.wikia.com

As we follow Kaladin through the first two books, he is a slave in one of the armies campaigning on the Shattered Plains. One of the worst duties for slaves was to be part of the bridge crews used by certain Brightlords to cross over the chasms common to the Plains. Without bridging units, the regular armies could not cross the chasms to engage in direct action with the Parshendi and capture the Gemhearts much sought after by the Alethi nobility. Since the Parshendi are indiscriminate in their targeting of troops, and the bridge crews are provided no defenses, this duty is effectively a suicide mission.

Kaladin recognizes two challenges the bridgemen face. First, there is no organization and training involved with their role. Itâs chaotic every time a bridge departs, with limited order provided by the slave masters. Second, without any hope of surviving, there is no motivation for the crew to do anything other than the minimum possible. After all, why try harder if you are only going to die?

Sanderson uses this context to provide a plotline that follows Kaladin as he leads by example and trains himself first, then others in basic military disciplines and builds cohesion within Bridge 4. Slowly, results begin to show. More of the men survive each bridge run. Minor changes result in significant improvements to their odds. The discipline builds up a sense of camaraderie among the bridge, and Kaladin is able to demonstrate the effectiveness of his methods in training for other bridges. A severe conflict is raised between the Brightlords of Sadeasâ camp, the lord who primarily uses slaves as bridge fodder, and Kaladin who is trying to save as many of his brethren as possible.

Kaladin also goes on to train his bridge crew in the use of the spear. He falls back on his own soldier training from his previous life in Lord Amaramâs army as a means of further developing the basic skills his team can rely on. The spear represents a useful tool on the battlefield, a means of standardizing a training regimen, and a way to baseline the troops. If nothing else, they can all use this most basic weapon and contribute as members of the infantry.

Itâs only later in the storyline that we see the crew introduced to new weapon systems (like one member gaining Shardplate and a Shardblade) and assuming their role as guard force. Something that should stand out is how those soldiers evolved from beaten-down slaves to an elite bridge crew to training spearmen to trusted guards. Sanderson shows us that development over a long, winding, maybe overly detailed story that helps us bond with favorite characters and invest in them, creating an even greater emotional commitment to a simple storyline of two races at war with each other.

In modern military forces such training occurs after the most basic military training activities (i.e., boot camp), and builds upon the foundation created there. This is especially true of combat arms units that employ crew-served weapons, where there is a unique combination of individual technical skill and teamwork necessary for a successful crew. Itâs hard to achieve this before basic military disciplines are a part of a soldierâs life. Some specific skills we see throughout history:

- Infantry setting a shieldwall

- Cavalry charging in an organized and synchronized manner

- Archers firing from horseback for skirmishing

- Operation of any siege engine (catapult, trebuchet, onager, ballista, etc.)

- Pike or halberders setting a spear line against cavalry

- Archers firing in sequence and by verbal order

- Vessels and aircraft being capable of firing with limited or no interference among allies

Any of these can make a great plotline, even simply backstory, for your characters who come from or are involved in a military setting. And as Travis P mentioned, your unique world-building will have new opportunities to do the same, whether itâs magic, a new weapon system, or other plot elements.

The Christmas season is over. If you subscribe strictly to the church calendar, the season might linger on until Saturday. But as a general social rule, the Christmas season is effectively over after New Yearâs Day. Now itâs time to get back to life and start the new year (2019: What Could Go Wrong?). So as we turn away from the holidays and back to life, here is a parting reflection.

The Christmas season is over. If you subscribe strictly to the church calendar, the season might linger on until Saturday. But as a general social rule, the Christmas season is effectively over after New Yearâs Day. Now itâs time to get back to life and start the new year (2019: What Could Go Wrong?). So as we turn away from the holidays and back to life, here is a parting reflection.

Excessive running times are one of the annoyances of modern movies. Theyâre a particular hardship in bad movies, of course, where (to paraphrase the great C.S. Lewis) length of minutes is only length of misery. But they dampen good movies, too, stirring up restlessness just when the story is rousing itself to its climax. There is the rare movie that can extend to behemoth lengths without losing power or charm, but the key word in this statement is rare.

Excessive running times are one of the annoyances of modern movies. Theyâre a particular hardship in bad movies, of course, where (to paraphrase the great C.S. Lewis) length of minutes is only length of misery. But they dampen good movies, too, stirring up restlessness just when the story is rousing itself to its climax. There is the rare movie that can extend to behemoth lengths without losing power or charm, but the key word in this statement is rare.

Did you catch that date? Submissions will be accepted until midnight (Eastern time), January 21. That’s in one week, folks. One week!

Did you catch that date? Submissions will be accepted until midnight (Eastern time), January 21. That’s in one week, folks. One week!

Two of the most popular 2018 articles on Speculative Faith share a surprising connection.

Two of the most popular 2018 articles on Speculative Faith share a surprising connection.

And this year,

And this year,

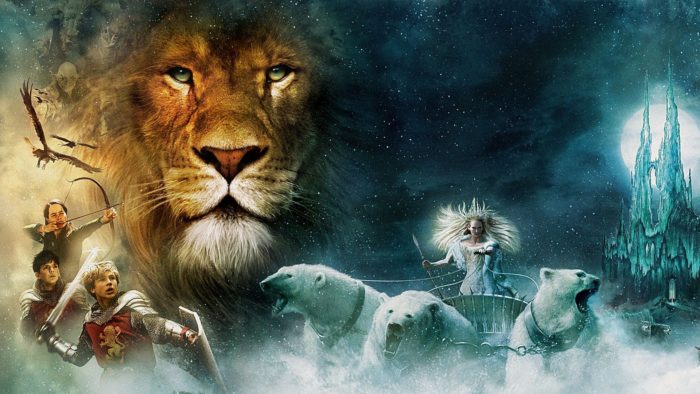

For example, in C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books, Aslan is the author’s answer to “What would God look like in this world?” In other stories such as Superman or Captain America, fans and readers or viewers who are Christian, if not the creators of the narrative, see the Savior depicted by the fictitious savior who does a sacrificial act to rescue those in danger.

For example, in C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books, Aslan is the author’s answer to “What would God look like in this world?” In other stories such as Superman or Captain America, fans and readers or viewers who are Christian, if not the creators of the narrative, see the Savior depicted by the fictitious savior who does a sacrificial act to rescue those in danger.