Nine Marks Of Widescreen Stories, Part 5

By day’s end, three million people will be carriers of the deadliest virus in history. There is no vaccine. There is no anti-virus. The world’s only hope is Thomas Hunter, and he has already been killed. Twice. Enter an adrenaline-laced epic where dreams and reality collide — and the fate of two worlds hangs in the balance of one man’s choices.

— Plot summary for Black, part 1 of The Circle Trilogy, 2004, Ted Dekker

“Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise; its continuing mission: to explore strange new worlds — to seek out new life and new civilizations — to boldly go where no one has gone before!”

— Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart), opening credit introduction, Star Trek: The Next Generation

It’s the year 1878! Sierra Samantha Victoria Hutchinson Dick Cheney O’Regan Begorrah Lancaster is a (select one: frontier doctor/lawyer/U.S. Marshal, daughter of Irish immigrants, abandoned orphan, child of Stern Amish Upbringing), who is (select one: trying to make her way in a career dominated by Men, struggling to understand a new land and find true love, struggling with her own loneliness brought on by the man who left her behind, trying to reconcile her faith and childhood abuses).

Will her faith in God be put to the Ultimate Test?! Maybe.

— A scientifically hybridized, generated back-cover text summary of approximately several hundred bestselling Christian paperbacks

5. An adventurous spirit, boldly going beyond small-scale stories

As they say on Sesame Street, “one of these is not like the other.”

That’s because, similar to last week’s fourth mark of widescreen fiction, An in-depth focus, with epic themes, a crucial aspect of speculative stories is a tendency to think in larger worlds, expanding a reader’s mind — beyond the familiar and the comfortable.

Perhaps it’s just me; I certainly realize not all people are the same in this regard.

And yet, though I hesitate to mention it without further Scriptural study, I carefully submit this: Might widescreen, speculative stories actually be spiritually “superior” to the smaller, “comfortable” tales?

Games of risk

One aspect of true Christianity that doesn’t get a lot of press now-a-days is the profound and freaky-scary element of risk that Christ called His followers to take in following Him. In the olden days, you could get thrown to the lions. In the new-en days, you could get laughed at on campus or by an in-law or two — an annoyance, but hardly dangerous.

So is it then wrong that we have it so easy in 21st century America, where religious freedom does exist?

I don’t think so. If God wanted us all to hide in catacombs, He wouldn’t have arranged for the U.S. and other religious-freedom-friendly nations, and He wouldn’t have put us here. We needn’t feel guilty for not living in one of those places where Christianity is illegal.

But even for those of us who remain in safer spots — is it not fitting that we recognize the dangerous aspects of the real world in our imagination, if it isn’t part of our reality?

Again, this next may seem controversial. But I might submit that we can grow more spiritually from our “widescreen” stories then we do with the somewhat human-centered, contemporary here-and-now stories that overall simply don’t stand the tests of time. Also, consider the amount of books on our shelves, both fiction and nonfiction, that would seem at all relevant to anyone outside of Western civ — persecuted believers China, for example, assuming they have time to read fiction.

Forging frontiers

On Monday, Rebecca LuElla Miller reminded Speculative Faith readers of the top-ten highest-earning films of all time, nine of which were fantasy / sci-fi-themed.

This continues to confuse me: why the Bible, the most “speculative,” fantastic and best-selling book ever, has nevertheless yielded a faith whose adherents mostly consider the most incredible parts as nice (though true) stories, and leave the epic good-versus-evil stories to the secular realm.

Further research might help us understand more of how the problem originated. But for now, the catch-22 seems to exist: speculative readers don’t believe they can find their favorite genre in the CBA; thus, CBA publishers are averse to publishing widescreen because the readers won’t expect it there; and the readers won’t expect it there because the CBA doesn’t publish it — and so it continues, the Great Circle of Life, ad infinitum.

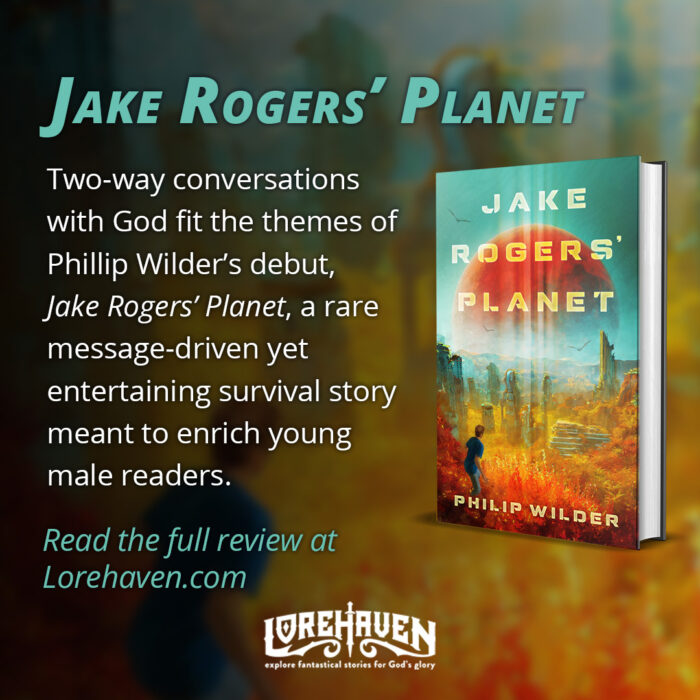

Anomalies exist along in the CBA, of course, giving hope to everyone. Despite the smaller, less-adventurous themes of most Christian books, widescreen authors have sneaked through: Frank Peretti, of course, and Ted Dekker, Stephen Lawhead, Joel Rosenberg, Donita K. Paul, Bryan Davis, et. al.; and yes, those Left Behind guys also count — what could be more speculative than the end of the world?

Might we assume that some of these popular, and increasingly popular, authors have achieved these profiles because their publishers have dared to take risks?

But they understandably won’t increase that risk-rate until more readers are willing to take the same risks, going outside their comfort zones into broader, pulse-increasing adventurous epics. Unfortunately, this market consists mostly of church attendees — many of whom aren’t necessarily known for fantasy/sci-fi, speculative mindsets.

God of adventure, God of widescreen

I hope to further this concept in the last three installments of the series.

But before members of the Church will accept more widescreen fiction, they will need to accept a bigger God.

He’s the Biblical God, not just of home and hearth, easy chairs and padded pews, but a God Who is running the show, Who doesn’t have a man-shaped hole that only we can fill, and Whose servants wage war daily against evil and basically do try to do something “cliché” like Save the World. To Him, our small-scale lives, “felt needs” and relationships and all that are certainly important. And yet, they only fit into the grand scheme of things — they needn’t be the sole focus of all our stories. (I hope to address this further, specifically regarding the element of Romance, in the next installment.)

By His very nature, the Almighty is the most awesome, epic, space of infinitude one can’t imagine. No words can describe Him; no picture, portray Him — we can barely even conceptualize the size of a galaxy, much less a universe filled with millions of them, much less a Creator of it all.

In that context, then, non-speculative stories are just as spiritually significant as the widescreen epics, in God’s perspective. Thus, the subcreated Sierra Samantha, etc., etc., can bring just as much glory to the Creator as Thomas Hunter; it is the heart of the human artist that counts.

Yet I for one can gain more from the timelessness of an epic-minded, adventurous fantasy story than I could ever gain from Sierra Samantha’s prairie romances. And here the weird term “inspirational,” too often used to describe cushy religious books, is actually relevant: for at the end of a speculative story, I want to be inspired.

Inspired for what? — merely to sit there and think about how lovely the story is?

No. I want to be inspired to do something: learn more about the Creator, work to enjoy His glory, explore strange new worlds, seek out new life … continue on an adventure, this risk-imbued journey that following Him truly is … and of course attempt my own works of epic, widescreen drama.

Reality here can already be small-scale. Why continue to produce only more stories that are the same?

Share your fantastical thoughts.