The Mirror Theory Of Speculative Fiction

I once heard a speaker say that good fiction mirrors reality. This can be easy to see in historical fiction or contemporary fiction. Of course it mirrors reality. It’s our world, just a few non-real people and places thrown in. It could be real, under the right circumstances.

I once heard a speaker say that good fiction mirrors reality. This can be easy to see in historical fiction or contemporary fiction. Of course it mirrors reality. It’s our world, just a few non-real people and places thrown in. It could be real, under the right circumstances.

But what about speculative fiction? Fantasy and science fiction and the other “weird” genres often don’t look remotely like our world. Can that be a mirror?

Yes, it can. After all, mirrors come in all shapes and sizes. They can be tilted and turned, which changes the reflected picture. There are the mirrors in the fun houses at county fairs that make people thin or fat or give them extra big noses on their balloon-shaped heads.

Perhaps, mirrors can even show reality more clearly. Sometimes in a mirror, shadows and light are more stark. A sunbeam that isn’t visible in the room shines on the mirror and turns the mirror world into a dazzling, sun-doused version of the much darker room it reflects. Words written upside down or backwards—gibberish as they currently are—can be read in a mirror.

Historical fiction or contemporary fiction is a pretty, but standard mirror. But speculative fiction is a tilted, wacky mirror that highlights different angles than other types of fiction.

As Christians, our reality looks different than in secular fiction. Our reality has a God who created the world and sent His Son to die to redeem His people. It has stuff like miracles, walking on water, plagues, and a world-wide Flood. All stuff the “reality” we see around us with just a physical eye says is impossible.

Speculative fiction, in that sense, is more important to Christians. Speculative fiction takes out the “reality” that only serves to mask God’s reality as revealed in the Scriptures. In speculative fiction, Christians can highlight spiritual warfare, the depths of darkness, the utter brightness of light, and the rumbles of God’s power that courses through the world hidden by physical reality.

Fantasy, science fiction, and the other speculative genres show all this by what doesn’t change in Christian speculative genres, no matter how strange and unfamiliar the world might be. God’s greatness and power doesn’t change. The beauty of redemption doesn’t change. Light and dark doesn’t change. Christian speculative fiction mirrors this in a vast variety of ways, but it is there.

In that way, Christian speculative fiction is more real than the physical reality we see around us. Our jobs, worries about money, and life distract us from the deeper reality we’re supposed to be seeing.

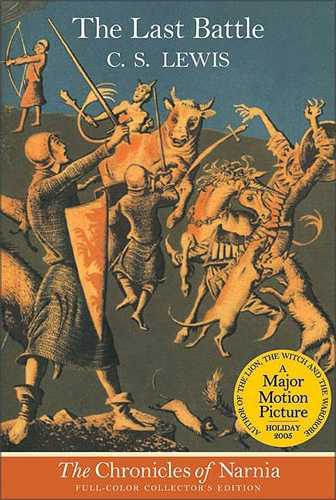

C.S. Lewis says it much better than I can at the end of The Last Battle:

C.S. Lewis says it much better than I can at the end of The Last Battle:

It is hard to explain how this sunlit land was different from the old Narnia as it would be to tell you how the fruits of that country taste. Perhaps you will get some idea of it if you think like this. You may have been in a room in which there was a window that looked out on a lovely bay of the sea or a green valley that wound away among mountains. And in the wall of that room opposite to the window there may have been a looking-glass. And as you turned away from the window you suddenly caught sight of that sea or that valley, all over again, in the looking- glass. And the sea in the mirror, or the valley in the mirror, were in one sense just the same as the real ones: yet at the same time they were somehow different–deeper, more wonderful, more like places in a story: in a story you have never heard but very much want to know. The difference between the old Narnia was like that. The new one was a deeper country: every rock and flower and blade of grass looked as if it meant more. I can’t describe it any better than that: if you ever get there you will know what I mean.

It was the Unicorn who summed up what everyone was feeling. He stamped his right forehoof on the ground and neighed, and then cried:

“I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now. The reason why we loved the old Narnia is that it sometimes looked a little like this.1

Tricia Mingerink

This is perhaps why we love speculative fiction so much. We catch a glimpse of the real country in the fantasy ones, just like we sometimes spot flashes of the real country in our own world. Speculative fiction shakes us from our comfortable lives in this world. After all, we aren’t supposed to be completely content with this world. We’re supposed to be longing and looking for something better. If we wish we could live in Narnia or Middle Earth or Ilyon or the Goldstone Wood because they feel greater and more beautiful than our own world, it is because we know there is a world to come that is more beautiful and better than the world we live in now. After all, our world is itself only a mirror—a tainted, flawed, pitted, dark antique-glass sort of mirror—of things to come.

- C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle (New York: Collier Books, 1976), 170. ↩