Join Our June 11 Livestream On How Authors Can Escape the ‘Writing for Writers’ Echo Chamber

For whatever growth God has granted Speculative Faith, and now the Lorehaven project, we might attribute this one manmade reason:

We have chosen to focus on fans, not writers.

Beyond the ‘writicism’

Back in 2013, I codified this renewed focus in the article The Forgotten Reader. In this article, I recalled:

Seven years ago I attended my first writers’ conference. That was a heady experience:

Wow here are other writers just like me who like writing about actual science fiction and things like that and best of all from a Christian perspective so where do I sign up and will you listen to my very naïve science-fiction novel proposal please with a minimum of laughing?

It bore fruit. That’s how I made real- and aspiring-author friends. I joined Speculative Faith. That site grew. Other sites, networks, independent publishers, and even some traditional Christian publishers’ slow acceptance of some fantasy, also grew. That’s fantastic. And it’s likely true that any growth here may be better than none.

But this can reach a plateau. Many websites and writers neglect the main reason they should grow. They turn into what I’ll call Writers Who Write about Writing for Writers Who also Write about Writing. Writers end up practicing writicism.

No, I’m not saying this is sin. I’m saying it’s limiting. It’s shooting ourselves in the foot.

We’re doing the same thing we’d do if we decided: Hey, let’s try not to reach out to regular readers.

Focus on the fan-ily

Some years ago, this focus on fans, not writers focus became more of a guiding policy here at SpecFaith.

At least, this was certainly my hope as the writer who helped reboot the site in 2010.1

For example:

- We began encouraging guest writers to focus on universal story ideas, not writing tips and tricks.

- We all but banned professional industry-talk about agents, editing, publishing, and such-like.

- For my part, I became near-legalistic about SpecFaith writers’ phrases like “as writers, we …”

- (In such legalisms, I became a nonfiction Editor, and I have no regrets.)

How did this fan-focus help SpecFaith and later, Lorehaven?

This decision to focus on fans, not writers, probably brought short-term loss but long-term gains.

By “short-term loss,” I mean that for a large segment of dedicated writers who spend a lot of time on websites, they may have felt SpecFaith became less practically useful to them.2 As we became more fan-focused, you couldn’t come here expecting to learn about verb tenses and protagonist arcs. For proposal formatting and agent-seeking, you’d have to look elsewhere (such as the fine folks at Realm Makers!).

But by “long-term gains,” I mean that our audience has certainly grown thanks to our emphasis on fans.

- We still talk about stories in-depth, but from a place of mainly receiving them, not just making them.

- Generally (for my part) I think we try to avoid authorly jargon. Disregard protagonists; acquire heroes.

- We put far more time into cultivating the Lorehaven library and especially the reviews section.

Break out of the echo chamber

On this I’ve much more to say. However, I’d also love to hear your thoughts as fans, authors, and anyone in between.

Therefore, I invite you to join us this Thursday, June 11, for a special livestream event at Realm Makers on Crowdcast.

What and why: When writers only write for other writers about writing, we ignore readers! Join this quest to overcome “writicism” in our marketing so our stories can find more fans.

Where: Realm Makers on Crowdcast

When: Thursday, June 11 at 8 p.m. (7 Central)

How: Sign up for your place in line here. You can get notifications when the event goes live, and for future Realm Makers livestream events. Crowdcast watchers can interact in chat, answer the poll question, and pose their own questions. (The video will also be mirrored at the Realm Makers page on Facebook, but without the interactive options.)

Meanwhile: Hear how top authors address ‘PG-13’-rated story content

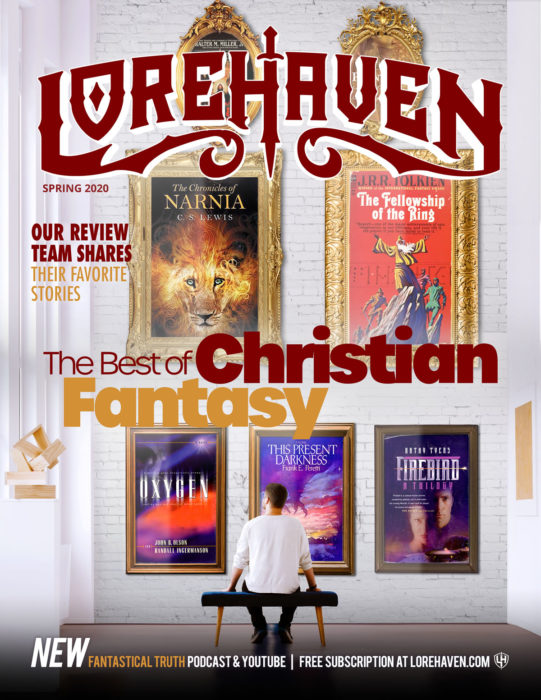

To be sure, we share plenty of fantastic behind-the-scenes content across the Lorehaven star system.

The latest such craft-building delight just dropped today at the Fantastical Truth podcast. In our latest episode, you can hear how authors Terry Brooks, Brent Weeks, Robert Liparulo, C. W. Briar, and myself explore that constant challenge of “PG-13”-rated (or worse) content in fiction. That’s courtesy of our friends and allies at Realm Makers, who provided the panel recording from last year’s Realm Makers conference.

Get the full show notes, or listen below to the complete episode 19.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

- I make these mild disclaimers about the reader (not writer) focus because SpecFaith has volunteer writers who choose their own topics. Apart from light touches for headlines and social media shares, we have no editorial structure for regular writers. Heavier edits are reserved for reader-submitted reviews and guest articles. Lorehaven magazine also has a set editorial structure. By the way, this is partly why we don’t have an open submissions policy for Lorehaven magazine articles and reviews. ↩

- I base this on general observation about trends, and no specific feedback. ↩

It’s interesting to think about targeting fans instead of other writers. Technically a lot of authors are doing that, even if they feature a lot of writing advice, and there are a lot of fansites out there. But Specfaith actually seems like it’s useful to both, without being so overt about the writing part that it chases regular readers away.

Something that’s been useful for me, in terms of learning how to address readers, is to pay close attention to comment sections and the trends in fandoms I like or that have similarities to my work. This can help authors learn a lot of things, like the intrinsic reasons for people shipping certain chars together and how they can build and talk about those ships(romantic pairings) in a way that engages their fans.

Your mention of terminology is interesting and sort of reminds me of the debate over ‘big words’ in stories, especially children’s stories. A lot of people say to avoid big words, and there’s an extent where that’s true. Using too many uncommon words can bog down the prose with things readers have to look up in order to understand. That might be especially frustrating to children, but that doesn’t mean that ALL big words should be avoided. One youtuber I listen to complained that the word ‘acquiesce’ was in a kid’s book(from the Warrior cats series) Acquiesce isn’t THAT hard a word. There’s a chance someone can pick up its meaning based on context. And if it’s one of the few ‘big words’ in a story, then it challenges and educates most young readers without causing an issue. Plus, Warriors is a fantasy book, and a fun aspect of certain types of fantasy is its use of formal language. The added benefit is that readers learn what a lot of formal words mean.

Extending that to the idea of avoiding writer centric jargon…that can have merit, in the sense of not clogging the site with it. But a little bit of writer jargon is a very good thing, because it helps people learn, even if they aren’t writers. And using writer jargon can help articles be clearer in their meaning. Protagonists and heroes are not the same thing in a lot of cases. Yagami Light is a protagonist, but not a hero by many definitions, even if he might think he is. Protagonist and hero are often used interchangeably, but protagonist usually refers to one of the main chars, whereas, hero has the connotations of morally good behavior or fighting for the right thing. Light wanted to get rid of all the bad people in the world, but even though his goal comes from a good place, he hurts a lot of innocent people and basically ends up being a tyrant. So calling him a hero runs the risk of implying that his behavior is good.

Good episode. I agree with a fair amount of what they discussed, though I think when addressing sexual issues I’ll mostly do so through implication, character conversations, etc. A lot of times it’s the causes, effects and mindsets of these situations that need to be addressed, and helping readers notice those, even when they’re subtle, can go a long way in helping people identify/avoid those issues in real life.

Something I will point out though is that, even though authors should be reasonably conscious about what they depict, there’s no way they can actually account for every person. Of course they can analyze fan behavior and INFLUENCE their reactions on multiple fronts, but in a large pool of readers there will probably always be some that react differently than the author likes, even if those people never say anything. It doesn’t matter if someone writes the most innocent family friendly show ever. Someone out there will invent a dark or crass fanfic about it, whether that fanfic stays in their heads or gets posted online. So a lot of it is actually on the reader, even if the authors should try to influence their readers positively.

Which means that authors can’t completely eliminate the possibility of lustful reactions, at least assuming they keep writing interesting chars and situations. One thing I’ve noticed while lurking around fandoms is that the character’s appearance, flirting, or inappropriate behavior isn’t always what triggers lust in the audience. Like, sure, it helps in a lot of cases, but sometimes if a char behaves that way too often they might just come off as obnoxious. And if the char is a pretty face and not much else, he might not be very noticeable to fans. Like, these are stories we’re talking about. Lots of other chars are good looking, too, but don’t automatically garner much attention. And in anime, so many of the chars have the same basic facial structure, so their looks can get somewhat redundant. So the char’s portrayal, behavior, backstory, beliefs, etc. can actually play a huge role. Not necessarily in the sense of all readers liking the same chars, but in the sense that each reader needs a reason to pay attention to the char and either A: find them fascinating, or B: have at least a vague bond or sense of sympathy.

This can happen in a purely platonic way, where the reader simply cares about what the chars go through and therefore roots for them. But I’ve noticed that it can have an impact on who readers ship or find attractive in the first place. It’s practically like the fans having a crush or falling in love. Sometimes they may do so in an innocent way, but sometimes there can be an element of lust to it. It’s not necessarily that the author did anything wrong…in fact, it can mean the authors did all the right things, such as making cool chars with interesting pasts and interpersonal interactions. But in real life, people are not only attracted to each other’s looks, but also their behaviors and the relationship they build with them. So it shouldn’t surprise authors when some readers have that kind of reaction to a char they like.

That said, readers will ship almost any pairing. Like, if you had a machine that picked two random chars every minute, each one of those pairs would probably find one person that would ship them, even if only as a joke.

Ok, one more post. As someone that was raised fairly conservatively and also doesn’t struggle with lust as much as other people seem to… Growing up I had a somewhat harder time being understanding toward other people’s struggles in that area. I mean, I didn’t really say much about it, but when reflecting on such issues I could ACKNOWLEDGE that temptation was difficult for people, but part of me just didn’t understand what that would actually be like for them. So I had an oversimplified view of things, which could have made me a little less useful if, for some reason, a friend asked me for relationship advice. But I pay tons of attention to the cause and effect of what other people say and do. And while writing I do my best to put the readers fully within the char’s shoes. Considering how varied my characters are, that means having to understand people that aren’t like me at all, in terms of perspective and interacting with the world around them.

Because of that, I understand a lot more than I used to and have a better chance of writing chars that actually help people. None of that would have happened if I completely censored what I read. Granted, I definitely still avoid actual sex scenes, but reading stories that at least portray varying viewpoints on sex helped a lot, especially when I read the accompanying author notes and reader comments and analyzed them.

Exactly what people should read will vary. And people need to be honest with themselves. Are they doing research, or are they doing ‘research’?

I still haven’t seen Beastars, but I listened to a couple more analyzations of it that got me thinking of some things. It sounds like it discusses a ton of important issues in a deep way, both in terms of society and individual struggles. But it does seem to have a lot of scenes dealing with sex. Maybe not full on sex scenes, but certainly a lot of uncomfortable ones that get pretty close to the chars actually doing something. But from the analyzation I was listening to, it sounds like those scenes were there for a reason, to discuss important issues. Mainly in that Haru was making bad sexual choices in her life and was judged and bullied for them. It seems that the audience is given a chance to develop compassion for her while she learns from her mistakes.

The Beastars chars look a bit…uncanny. Like, they’re humanoid animals, and the mishmash of human and animal traits looks weird on these chars. I’ve even seen people say negative things about the chars’ eyes and such. So from that standpoint my first reaction was that this could be a way to discuss sexual issues without inciting lust in as many people. To an extent that’s true, since less people would probably be attracted to this. But the obvious fact is that some people will still be attracted to it. And then there’s the fact that people might react with lust simply because the situations/discussions are sexual, not necessarily because they actually feel attraction to the chars. So…I dunno. I have a feeling they went a little more explicit than they needed to, but the situations at least have a purpose beyond fanservice.

But what people need to be aware of and prepare for is the way their reading and writing choices come across. Regardless of the intentions the author of Beastars had, people are going to make a lot of nasty assumptions about it and therefore be less likely to understand the valuable lessons it might contain. So if someone writes that stuff, or even reads/watches it, especially as a Christian, they better be pretty aware of how that comes across and be ready to have a well thought out conversation about it to clear up any misunderstandings.