First Man: An Example of Fearlessness

My fellow Travis (Chapman) is going through some personal difficulties at the moment, and I am too. So for this week I’m taking a break from our Speculative Fiction Writer’s Guide to War series to talk about a movie I watched yesterday–First Man. I think this movie shows an example of the type of fearlessness seen in warriors that T-2 wrote up in last week’s article on the nature of warfare.

First Man, for those who may not be familiar with it, is a highly realistic movie about the astronaut Neil Armstrong and the first landing on the moon. As such, while the movie is mostly straight-out confirmed biography. It strays into historical fiction at moments because nobody remembers some of the conversations it records and it also shows at least two events that for certain did not happen at all or not the way the movie portrayed them (I did a bit of after-viewing research). Which includes a moment the film gives great emotional importance on the surface of the moon (if you’ve seen the movie, I’m sure you’ll be able to guess what moment I’m referring to).

It’s not really a speculative film at all in the ordinary sense of the word, but I hope you will excuse me posting about it here. First of all, it contains moments of danger and drama, life or death issues for Armstrong–all of which actually happened, but which still are cut from the same cloth as drama you’d find in a speculative fiction plot. Second, it shows the best Hollywood portrayal of what landing on the moon was like–it really feels like the viewer is along for the ride. And the moon looks amazing in First Man–a totally alien surface, a place unlike anything anywhere on Earth. Which really stirred my longing for other worlds and places, a longing most often expressed in speculative fiction.

I’ve also got a third reason for writing about this movie, one I already revealed in my first paragraph. I think the movie shows a character portrait of the kind of fearlessness seen in warrior elites. That which characterizes a person who winds up being a hero in war–or in the case of Armstrong, in space. (I’m not mainly writing a movie review, but I’d give this film 4 out of 5 stars. FYI.)

Note though that this movie is very much focused on Armstrong personally. Not only the dangers he faced in the air and in space, but wife, his marriage, his children, and his friends. The camera angles are often close–you see a lot of Ryan Gosling’s face in this movie (and of other key actors). The film is not about NASA as a whole, even though many astronauts are portrayed. It makes only minimal efforts to explain what the space race was for or what was technically going on at any particular moment of the film. It instead provides a visceral insight into what it feels like to be physically jostled around, to hear the groans of aircraft wings, to have the sound escape the lunar module as the air flowed out. (By the way, by focusing on the visceral in Armstrong’s life, it feels totally natural for the film to focus on Armstrong stepping on the moon and to skip Buzz Aldrin planting the US flag later on.)

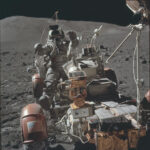

Gosling showing Armstrong boarding Apollo 11.

Armstrong himself probably only partially operated on the level of the visceral. He intellectually understood what was going on in a way the movie viewer would not and it seems his brain was highly engaged in solving his problems, not focused on what being there physically felt like. Though the movie actually portrays that, too, Armstrong in problem-solving mode, especially during his mission in Gemini 8, in which he saved his own life and his copilot’s life by cool thinking during a dangerous spin that he alone solved, without any guidance from Houston or anyone else.

The movie stuck to reality in portraying Neil Armstrong as stoic and cool-headed, the type of person who could make the right decision even under pressure and who had very little to say. I actually suspect that Gosling’s Armstrong is even more emotional than Armstrong actually was, yet there is no way to watch this film without seeing a portrait of a man who kept his emotions under control, who lived in his mind and intellect more than in his heart or emotions.

We could chalk up Armstrong’s fearlessness to his background and training (he actually was trained at the US Naval Academy and was a fighter pilot in the Korean War), but I felt when I watched the movie it was showing us something else. It portrayed the life of someone who would be a member of what I called “the Fearless Elite”–people who are wired differently than the majority of humans. People who are capable of feeling fear, but who are unaffected by it.

The movie also shows Armstrong not really being able to connect with his wife, with struggling to talk with his sons at a key moment. In other words, as someone who not only benefited from his emotional control, but who suffered the downside from emotional distance as well.

My fellow authors, that’s a realistic portrayal. Even if First Man overemphasized Armstrong’s lack of ability to connect emotionally (which I suspect it did), I think it was essentially correct in showing there is actually a downside to even the heroic kind of fearlessness. That is, a lack of ability to fully engage with others from the heart.

Thanks Travis! For those faithful followers, prayers appreciated. As you know, we are both still serving, both have had big life event stuff going on, and want to be the best resource for spec-fic authors writing about warfare. These seasons happen.

Also, I’m happy to reread to enjoy the portrayal of one of our grads. I can attest to the level of training this institution provides as I’m a product (Class of 2002) and a contributor. T-1’s analysis reveals an important lesson: those characteristics we value so much often (always?) come at a cost.