Beauty And Function

From time to time Christian evangelicals are criticized for our view of the arts. The critics believe something that is truly artistic can exist for no other purpose than to be truthful and beautiful. A song, a poem, a painting, a novel–none of those has to serve a greater purpose than to shine as art. In contrast, Christian evangelicals always want art to be functional–especially if the function is to declare something about God.

From time to time Christian evangelicals are criticized for our view of the arts. The critics believe something that is truly artistic can exist for no other purpose than to be truthful and beautiful. A song, a poem, a painting, a novel–none of those has to serve a greater purpose than to shine as art. In contrast, Christian evangelicals always want art to be functional–especially if the function is to declare something about God.

The ironic thing is, this criticism often comes from other Christians, and the next plank in their argument is to point out that God made beautiful things in the deepest parts of space which no human eye has seen until modern science captured these glories on film. Same with things growing at the bottom of the ocean. What function does the beauty of those objects hold?

Add to that argument, the one from the Old Testament about the beauty of the objects connected with worship—the priestly garments with the gem-studded breastpiece; the ark overlaid in gold and covered by the carefully crafted mercy seat with its gold cheribium; the perfumed incense; the curtains made of fine twisted linen and blue and purple and scarlet material, with embroidered cherubim.

God wanted all these things to be beautiful. He specifically picked out two craftsmen to “make artistic designs” though many of the objects would not be seen by the public but only by the high priest once a year.

So does beauty exist for beauty’s sake? Are evangelical Christians wrong to think art can and should do more than just be beautiful?

It’s a much more complex question than it appears on the surface. First, the “just be beautiful” argument neglects the twin arm of art–truthfulness. Real art is more than a picture of an angel of light because Satan himself walks around in that guise. He is not truthful, so regardless of his outward appearance, he is far from “art.”

If someone painted his portrait showing him as an angel of light, no matter how skillful the painting, it would still not be good art because it didn’t reveal truth.

If someone painted his portrait showing him as an angel of light, no matter how skillful the painting, it would still not be good art because it didn’t reveal truth.

There’s another principle to consider, though, besides the definition of art. That is the idea of an integrated life. When a person becomes a Christian, Scripture says we are made new. We have a new self. In other words, Christianity isn’t tacked on. It isn’t layered over top our existent lives. We’re not adding on a little religion like we might add on a hobby or a new friend.

Rather, Christianity gives a person a new core that ought to have radical implications all the way out to our fingertips. In other words, art is simply an extension of our Christianity in the same way that driving should be an extension of our Christianity or Facebook commenting should be an extension of our Christianity or getting our job done at work should be an extension of our Christianity.

In this view, all of life is “functional” in the sense that all of life should be a reflection of our relationship with God through Jesus Christ.

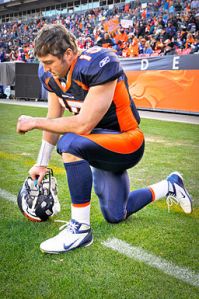

Tim Tebow comes to mind as an example of a man who is intentional in this regard. He wants others to know that at his core is this relationship with God that changes every other aspect of who he is.

Tim Tebow comes to mind as an example of a man who is intentional in this regard. He wants others to know that at his core is this relationship with God that changes every other aspect of who he is.

Some people hate that Tim talks about his faith so openly and so repetitively. Other people are attracted to the reality they see, whether he’s leading the Broncos to a playoff win, getting cut loose by the Patriots, or trying to catch on with the Eagles.

In many respects, Tim represents Christian fiction that is overt. Reporters who interview Tim know that there will be a point where he will talk about his faith in Jesus Christ. So, too, in some Christian fiction, there will be Christianity front and center at some point in the story.

Other Christians, even those in the limelight, are less verbal about their faith. A. C. Green who played for the Lakers alongside Magic Johnson comes to mind. His faith and his moral compass were the same as Tim’s, but he didn’t use every interview to draw attention to his relationship with God. Same with Clayton Kershaw, current pitcher with the Dodgers.

Is A. C. Green’s life or Clayton Kershaw’s more “artistic” because it is more subtle? Is Tim’s more “artistic” because the truth is front and center?

In my way of thinking, both are living integrated lives. Their Christianity comes out of their pores, but that doesn’t mean their lives must look exactly the same or that they handle all circumstances alike.

So, too, with art. Some beauty has a function. Male birds have more colorful plumage than their female counterparts for a functional purpose–to attract said females. The design of some animals camouflages them from predators. The sweet scent of flowers attracts insects that spread their pollen, and so on. God gave function to some beautiful things, including those Old Testament items involved in worship.

Because a piece of writing or a painting or a song carries an overt theme does not disqualify it from being artistically great. If the opposite were true, no great art existed in Europe until the twentieth century. Michelangelo wasn’t a great artist, Milton wasn’t a great writer, Handel wasn’t a great musician, Charles Wesley wasn’t a great hymn writer.

On the other hand, absence of truth does disqualify something from being great art, though not all truth is represented in any one piece of art. The function of some great art, then, is to depict something sinful–the crucifixion, Humankind’s rebellion against God or mistreatment of each other. These may have poignant beauty and gut-wrenching truth and be some of the best art of all time.

But function? As I see it, function does not qualify or disqualify a work from being artistic–and certainly not the function of declaring God’s glory or His work in the world or in the hearts of men and women. What could be a more truthful, more beautiful event than the change that takes place when “The Lord my God illumines my darkness”?

Originally posted, minus some slight revisions, in 2013 at A Christian Worldview Of Fiction

When we were discussing the difference between art and Art in lit class, one of my peeps’ criteria was offensiveness (more to the status quo than to the individual). And I think that’s true, if only because we’re more likely to remember it, lol.

E.g., I find impressionistic style paintings to be more memorable because it’s offensive to the photorealistic sensibility encouraged by photography and HDTV. Maybe I should phrase it “offensive” with quotes, because I don’t really find it offensive-offensive.

Interesting, Notleia. I’ve never heard of “offensive” as a definer of art. I suppose that would work today because undoubtedly a large segment of people who prefer Art are offended by the Christian themes of those Medieval artists and musicians.

Becky

A beautiful and timely post, when there is such a pull in Christian art and media between the “be overt” camp and the “go under the radar and speak the Gospel with actions” group. This is a false dichotomy. There is a need for both. And I would challenge overt message believers and under the radar believers to take care that they aren’t becoming proud in their position, as if how they show the Gospel makes them somehow better. And also, never say never. God may ask an overt Christian to show their faith with actions, or challenge an under the radar Christian to speak out.

Well said, Janeen. And yes, I thought discussing art was again necessary because there’s been a recent push against Christian themes. “Christian lite” one author called it.

Becky

The image of the male and female birds was quite intriguing. I may have to ponder that image for a while.

Kind of shatters what people commonly think about God and sex, don’t you think? 😉

Becky

Tolkien’s sub-creation theory generally seems consistent with this argument. One of my great privileges I’ve had in my unremarkable education was the opportunity to learn that Tolkien was inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement — a movement that emphasized authenticity and skilled craftsmanship in design (lettering/textile design) and home decorative arts.

William Morris was both a textile designer and a the author of one of the first fantasy books. Maybe the more English/humanities oriented people around here could say more about the relationship between A&C and contemporaneous movements in fine arts and literature, but point is there was a relationship. Practical applications and pure impractical artistry went hand-in-hand.

Tolkien wrote about creative beings — God’s creation, gods’ muddling and remixing of God’s creation, mortals creating powerful and real things that are also beautiful. He did not write about elves and hobbits who wrote their own fantasy novels, however. Without practical application, the dream of speculative fiction is vain. We don’t generally read stories about stories; we read stories about real things—and I think that we search for the wonder that we find in stories in the real world.

Thanks for your thoughts, Paul. I’m not familiar with the Arts and Crafts Movement, but from what you say here, it does fit in well with Tolkien’s sub-creation approach. I also like what you say about Tolkien’s invented people not making up stories. Very interesting! They made up songs and poetry, but their storytelling was history, not make-believe—something else I hadn’t thought of before.

Becky

I am impressed. You know about A. C. Green!

Martin, I’m a long time Lakers fan. How could I not know about A. C. Green! 😉

Becky

Love this piece, Becky. I wish I had caught it the first time around.

I think one reason why many Christians are so nervous about the truth that good art by Christians should be intentionally beautiful/good/truthful, and thus function as an expression of intentional God-ward-ness, is that we wrongly believe worship and praise of God are boring. We assume they are limited to (supposedly) dull and ritualistic practices such as church liturgy, or prayer and Scripture reading. Instead we ought to see that the purpose of these things is to train us for the tasks of intentionally “functioning” as God-glorifiers in all of life. And that function is no more un-beautiful than the function of a beautiful watch mechanism, or one of those beautiful nebulae drifting or quasars pulsing silently, unseen, far out in deep space.

Interesting thought, Stephen, that our expectation of worship may be something routine and uninteresting. I’d never thought about that before. Of course some people look at worship as a event that engenders emotionalism, so for them it’s not worship unless people are on the verge of tears or so moved that they want to clap or raise their hands. But of course worship isn’t about us at all and it really doesn’t matter what our emotional response is. We are the givers in worship, acting because of who God is and what He’s done. The focus should rightly be on Him and not on us.

Which is what I think Christian fiction should be at some level. Big topic. I don’t have time to elaborate in a comment. Maybe another post one day. ! 😉

Becky