A Pot Of Message

One of the complaints commonly launched against Christian fiction is that it is all so laden with messages. The artistic defects of this have been dissected, along with the grave insights it offers into our contemporary Christian culture. (Hang around long enough, and you will learn that just about everything offers grave insights into our contemporary Christian culture.)

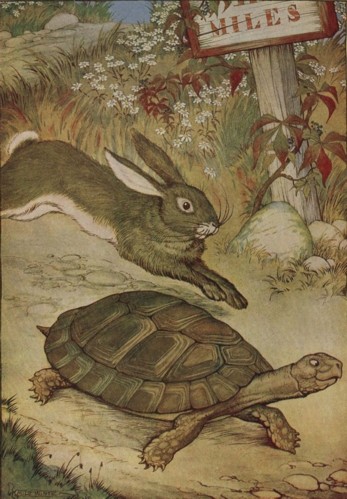

But it’s worth remembering that using stories in service of messages is an old and diverse tradition. Jesus Christ, Aesop, and many  long-forgotten originators of folk tales did so without compunction. Even the novel proper – a relatively newfangled art form – has quite a history of mixing art with messages.

long-forgotten originators of folk tales did so without compunction. Even the novel proper – a relatively newfangled art form – has quite a history of mixing art with messages.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin rendered an emotionally powerful and politically explosive portrait of the “peculiar institution”; it’s not without reason that the historian Paul Johnson called it the most successful propaganda tract of all time. It was the best-selling novel of the nineteenth century.

Charles Dickens, like Harriet Beecher Stowe, was not in his novels shy about his political and social views. Everyone can see that in his most famous creation; A Christmas Carol explicitly jabs at the workhouses and the Poor Law, and even takes aim at Thomas Malthus when Scrooge despises the poor as the surplus population. The backhand to Malthus is even clearer in the Ghost’s rebuke: “Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!”

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle told the story of an immigrant who worked in a Chicago meat factory. The novel helped to usher the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act, a landmark in the federal government’s expanding scope. But this was an accident on Sinclair’s part: He was trying to set forth the evils of “a system which exploits the labor of men and women for profit”. As he put it, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

H. G. Wells made plain in The Time Machine that the Morlocks were evolved from the Have-nots and the Eloi from the Haves, their division a result of “the gradual widening of the … social difference between the Capitalist and the Labourer”. He went religious with Mr. Britling Sees It Through in 1916, and then in 1917 explained himself in the nonfiction God the Invisible King. It got to the point that G. K. Chesterton remarked, “Mr. Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message.”

It’s an interesting criticism from Chesterton, who wrote The Man Who Was Thursday in response to the pessimism that brooded over some  literature in the 1890s; whose The Napoleon of Notting Hill is, upon analysis, an exposition on patriotism; who in The Flying Inn created a courageous, intellectual villain whose raison d’être was the prohibition of alcohol.

literature in the 1890s; whose The Napoleon of Notting Hill is, upon analysis, an exposition on patriotism; who in The Flying Inn created a courageous, intellectual villain whose raison d’être was the prohibition of alcohol.

George Orwell survived the bloodbath of the Spanish Civil War and in 1946 wrote an essay entitled “Why I Write”. There he stated: “The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” Three years later, he published 1984.

To bring the discussion into our own day, Darren Aronofsky said regarding Noah, “There is a huge statement in the film, a strong message about the coming flood from global warming.” Dean DeBlois, director of How to Train Your Dragon 2, explained the insertion of homosexuality into a kids’ film this way: “I think it’s nice. It’s progressive, it’s honest, and it feels good, so we wanted to keep it.”

So when I hear people criticizing Christian fiction for all its messages – and especially when I hear grave insights into American Christianity on account of all the messages – I wonder: Do they think we’re the only ones who do this?

And also: Why can’t we do this?

Amen! 🙂

Great thoughts!! I don’t feel called to share particular messages through my stories, but I often find messages in them as I flesh them out.

That seems like the better route to me. People who try too hard at theme tend to end up wielding it like a sledgehammer.

Please tell me the homosexuality reference for HTTYD is a joke. But the idea of stories with messages is not just a Christian thing–look at Cameron’s Avatar for a secular film that most people would call preachy.

Shannon:

Julie D:

(Nods gravely) It’s no joke. Here at SpecFaith in June I wrote an expose at Three-Second Comment Defeats Entire Storyline of ‘Dragon 2’.

Here’s the line: “This is why I never married. This and one other reason.”

It’s pretty innocuous, and left to myself I would never have interpreted it as a reference to homosexuality. In fact, if you just watch the movie and pay no attention to the commentary, you’ll find no homosexuality in it.

But if you do listen to the commentary, you’ll find that what they intended by that line is, to quote the director again, “Gobber’s coming out in this movie.”

I’ve had a long day, so can we try that again, shooting straight? *returns after checking site.?* As if the world wasn’t messed up enough…

So then, let’s skip the “you do it too, neener-neener” and start a conversation on how to incorporate “agenda” (it seems to need scare quotes) without it being crappy. Or just forgettable.

Because we have all of three messages.

1. Come to Jesus.

2. Abortion is bad.

3. Hey you! Navy SEAL! You need to marry this woman, pronto!

We used to have four, but…

4, New Age is bad!

…seems to have dropped off a cliff recently.

Seriously, it’s not so much message but the lack of variety.

LOLZ. Have a thumb.

It’s a sad/funny thought that it just might be possible to sum up the thematics of all Christian fiction in roughly two categories: 1) come to Jesus and herd as many as possible along with you; 2) Here is this single narrative of family friendliness we would like to press upon you.

I don’t think it’s possible not to have messages in the stories we write. Every author, whether knowingly or unknowingly, imparts some of his/her worldview into his/her writing.

Problems arise when we become so obsessed with the message that we forget the story. I believe if we focus on writing a truly great story the message will come along naturally.