What Is Intellectual Rigor?

In essence, when I wrote “Christian Speculative Fiction And Intellectual Rigor,” my Spec Faith post last week, I addressed what I believe intellectual rigor is not. It is not writing in such an obtuse way that only brainiacs can understand. It is not utilizing a story structure–and by implication, I intended to say, any other artistic device, even realism–that confounds meaning. It is not valuing how a story is told over what a story means.

In essence, when I wrote “Christian Speculative Fiction And Intellectual Rigor,” my Spec Faith post last week, I addressed what I believe intellectual rigor is not. It is not writing in such an obtuse way that only brainiacs can understand. It is not utilizing a story structure–and by implication, I intended to say, any other artistic device, even realism–that confounds meaning. It is not valuing how a story is told over what a story means.

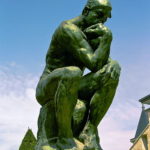

Only at the end of my article did I touch upon what I believe intellectual rigor, when it comes to fiction, actually entails: significance. In saying this, however, I need to qualify this point as I did in my last post. We are still talking about stories, not essays or sermons or non-fiction books. I believe a piece of fiction will not be significant unless it is a good piece of fiction.

Consequently, all parts of a story need to be given due attention. Characters need to be crafted in such a way that they are believable and realistic. They should be properly motivated and should develop in natural ways as a result of the circumstances of the plot. The events themselves should unfold in organic ways, one thing causing another in an understandable and logical manner. The setting also should be textured and fully developed.

But ultimately, the first three key story elements do not exist for themselves. They exist for the sake of the fourth, less conspicuous element: theme. All good stories say something. They have a point. After all, writing is a form of communication. Fiction writers, therefore, are making a statement, but they do so by showing rather than by telling.

It is this statement, this theme, I believe Christian writers must pay closer attention to, without diminishing our efforts in regard to characters, plot, or worldbuilding.

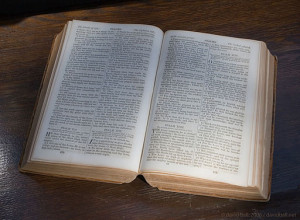

First, our themes need to square with Scripture. This point is perhaps the most complex issue for the Christian. Some writers sacrifice theme for the sake of art. However, the most artfully told story that says something untrue is nothing more than an artful lie.

First, our themes need to square with Scripture. This point is perhaps the most complex issue for the Christian. Some writers sacrifice theme for the sake of art. However, the most artfully told story that says something untrue is nothing more than an artful lie.

Some readers, and as a result, some writers, may become enamored with the beauty of the language, the depth of the characters, the realism of the world, or the intrigue of the plot. But a lie is still a lie. Good art will not only be beautiful but truthful.

On the other hand, some writers, and perhaps readers, confuse other elements of a story with theme. For example, I recently read one believer’s opinion that anything not squaring with the way God created the world, should not be in our fiction. Consequently, elves and hobbits and aliens and talking animals should be outside the realm of permissible Christian fiction.

Certainly I believe the Bible, and I believe a Christian’s fiction should square with the Bible. Does that mean every story must show truth in every aspect throughout? I suggest it does not. Stories in the Bible itself can best demonstrate this point.

In one of Jesus’s parables about prayer, He equates God with an unjust judge. Was He in fact teaching that God is unjust? Certainly not. That concept clearly contradicts any number of other passages of Scripture. The point of Jesus’s parable, however, was true.

In a story told by an Old Testament figure, trees were looking for a king, asking first one, then another to reign. The idea that trees talk and can organize a government contradicts what we know as reality: trees aren’t sentient. The point of the story, however, was accurate, even prophetic.

First and foremost, intellectually rigorous Christian fiction should deliver a Biblically true theme.

In addition, our themes need to be important to our audience. In this regard I agree with the intent of the commenter who criticized my post last week by saying, “Lewis engaged with and responded to (literary) Modernism, and I’ve yet to see anyone engage with Postmodernism in a way that looks genuine.”

The Christian understands that nothing matters in life as much as our relationship to God. Consequently, the MOST important theme, on the surface, is the one that presents Jesus Christ as Savior and Redeemer.

The problem, however, is that in our postmodern culture, many people believe Humankind is born good, or at worst, a blank slate. There is no need for a Savior, in this way of thinking, because there is no sin from which to be saved.

People influenced by postmodernism also believe in relativism and are apt to oppose authoritarianism. The idea of God as a judge condemning people to an eternal destiny in hell or as an all-powerful sovereign who allows suffering, grates against their moral understanding.

The Christian writer who offers Jesus as the answer in a “come to Jesus” type story is actually offering gold to a thirsty man. The giver of gold will appear to be foolish, even though he knows what he is offering will provide Everlasting Water and is precisely what the thirsty need. The thirsty man, however, will curse him for his insensitivity and look elsewhere for something to drink.

Intellectual rigor in fiction, I believe, means bridging the gap between what our culture perceives to be their needs and what Scripture says each of us actually needs. Sometimes that requires stories that don’t present Christ, at least not overtly and not even allegorically.

Instead, stories may need to challenge the postmodern assumption that there are many ways rather than one true way. They may need to challenge the assumption that seeking without expecting to find is wisdom, that God is mystery and therefore unknowable apart from whatever each individual perceives him to be. They may need to challenge the belief that now is all that truly matters, that pleasure is always better than pain, and that an individual has the answers within himself if he’ll only look.

Those stories would not contain the gospel, but they would challenge the presuppositions of readers influenced by postmodernism–presuppositions that can cloud the thinking of people in contemporary culture so that they do not understand what the gospel is all about.

Thus, when it comes to fiction, I’m all for the kind of “intellectual rigor” that makes stories eternally significant. Those stories may include an overt communication of the gospel, or not.

Great thoughts, Rebecca. I know I could use some more attention to, “What am I SAYING here?” while I write. Thank you for the food for thought!

Thanks, Bethany. I’m a believer in being intentional about what we say in our stories. It adds another whole layer of meaning. Glad this sparked some thoughts for you.

Becky

It seems to me that “intellectual rigor” definition all depends upon what aspect of writing fiction one is talking about. There can be some intellectual rigor demanded on the writing craft itself in various forms. It could be in reference to the science behind the story, or the consistency of world building. In what you are referring to, the intellectual rigor is on theme.

Both you and Mike, I think, were ultimately addressing is the intellectual rigor of addressing your target audience with meaning. Different approaches, but similar goals. One focusing on delivering the theme in a meaningful way within the story while another on those issues and themes that would relate to that audience. Overlap, of course, but maybe different starting points.

But a question. My Virtual Chronicles series I wrote to be fun space opera, with no intentions or goal of a specific theme when I sat down to write it. That’s not to say themes didn’t evolve from it, and reviewers see some I didn’t, but I didn’t set out to make the story say anything as such. Just a fun YA space opera story. Meanwhile, the Reality Chronicles is definitely theme, message oriented, with even a couple of “come to Jesus” moments in them.

Do you think there is a place in a writer’s list of works for both kinds, or is writing any story without an intentional theme a bad idea, as a Christian writer?

Both are acceptable. I don’t even see a problem with an author who only ever writes “fun” stories without “significance” or deep themes.

First of all, we err if we judge another for what they write. “Who are you to judge another man’s servant?” (Romans 14)

And secondly, there is always a place for enjoyment without overt message. God gave us taste buds — for pleasure. He could have made food nutritious without giving it flavor. Same goes for so many things in life. God made us for enjoyment of life. Children and otters and dolphins play for the delight of it. Beauty is gratuitous.

I see no contradiction with orthodox theology in having stories that are enjoyable simply for the enjoyment of them — given the assumption that they are enjoyed for reasons that aren’t at odds with His truth (enjoying porn may be enjoyable, but it’s still destructive).

It’s up to the reader not to overdose on the fun stuff, not to use your enjoyable stories to escape from the reality of his or her life.

Glad you’re writing both kinds, Rick!

Thanks, Teddi. I do, however have a method to my madness. 😉

I figure if I write good general market stories, it will entice those readers to check out my more Christian oriented books. Sort of a bridge strategy to gain more exposure for the books we often feel are stuck in the “void” between the Christian and general market.

I meant to say in my original post, Becky, that I’ve always felt my goal was to, “…they would challenge the presuppositions of readers influenced by,,,” fill in the blank -ism. I think fiction is a good vehicle for that, because a reader gets to experience someone else’s reality. Where their walls might go up in a discussion on the subject, they’ll be more open to seeing it in a character and their experiences.

Teddi, you made some excellent points. I think what you’re saying fits in what Stephen has said from time to time about our writing glorifying God because He is the giver of the talent and ability to write in a beautiful way.

I also like the idea that play is part of how God made us. The one thing I’ve found, though, is that play changes as I grow older. I don’t enjoy at the same level some of the games I played as a child. Games now take more planning, more skill. Applying that to my writing, I’d say I wouldn’t enjoy a story as well if it doesn’t also make me think. It can be a fine story, but if I don’t remember it tomorrow, I tend to steer away from the next one from that author. I don’t want to waste time on what feels to me like fluff. It’s like cotton candy. When I was a kid, I thought that was the end all for treats (probably because Mom hardly ever allowed us to have any). Today, if you offered me cotton candy or a tuna sandwich for lunch, I’d take the sandwich. The cotton candy wouldn’t take care of my real hunger needs.

Becky

Rick, I was presupposing that we’re already putting thought into how we create our characters, setting, and plot. I do think those need to be well crafted, but I don’t think that’s what Mike had in mind. Something you said in your comment to his post clicked with me–about theology of art. I still could be wrong, but I think Mike is reacting to the idea that art should be utilitarian, that Christians see it as a means to something else and not as an entity with value in and of itself.

Which connects with your question about your “non-thematic” stories. I tend to think it’s nearly impossible to have a no theme story. If a character develops, if someone wins, all these are tacit statements of meaning the reader can derive from the story.

Which is why I think we should be intentional. If we don’t think about what we want to say, we will probably say something fairly shallow (honesty is the best policy, love wins in the end, don’t forget to fuel the space ship 😉 ).

I agree with Teddi, though. I don’t think it’s up to any of us to judge another writer’s decisions. If someone asked my opinion, I’d say, non-Christians care about depth as much as Christians do. There’s lots to say in a story that isn’t overtly Christian and yet might spark deeper thinking for a general market readership. I’d suggest doing that than trying to write something light with the idea that those readers will then enjoy your more thought-provoking, more Christian thematic stories.

Becky

Thanks for the thoughts, Becky. Yes, I too don’t think Mike wasn’t referring to craft. I think you are both thinking with the same goals, but different approaches.

On the topic of intentional vs. unintentional theme, I get what you are saying, but let’s explore this a bit more to see if we can gain more clarity.

There are two valid ways for a theme to emerge. One is to decide what that theme will be and write a story you feel will highlight that theme. The other is to find a good story to write, and see what themes arise from that story. Either method can produce deep or shallow themes. IOW, I’m not sure the goal to tell a light and fun adventure of necessity means shallow themes.

You are correct that even when you are not putting theme into a story intentionally, that they arise. In the Virtual Chronicles, for instance, I realized about halfway into writing it, that a theme of trust was bubbling to the top. That theme has continued to pop up as I wrote the other two books. One reviewer identified it as themes of friendship and loyalty. But I didn’t start out to write a story to illustrate those themes. They simply arose from the experiences and decisions of the MC and his friends.

Now, I don’t think it is the intentionality or lack thereof that can make it shallow. I don’t think it is the theme itself that makes it shallow. Rather, it is how that theme is integrated realistically into the experiences of the characters in a way that allows the reader to authentically experience that theme/truth and get them to think about it.

That can actually happen more authentically when it arises naturally from the story than when someone starts looking for a story to tell that highlights a theme. Not that the later can’t happen, but it takes skill to make an intentional theme appear to have risen organically from a story instead of the story serving to illustrate a theme.

Barring literary works which are theme driven, most non-Christian, even Christians, when they pick up a story, if they catch a whiff that the author wrote a story to tell a truth, will react negatively. Which is why a lot of CBA stuff is limited to the CBA and often doesn’t cross over into the general market. It can, but it is rare. Mainly because general market readers suspect, it not blatantly obvious in the story, that the author wants to save them. Which is why one reviewer returned my novella, “Infinite Realities” with the note, “I don’t review Christian propaganda.”

One more point. It isn’t the idea that a theme is present, so much as what the theme is. What makes it taboo isn’t that there is a theme, but that the theme is contrary to one’s perspective. A story that illustrates the evils of racism won’t get too much push back, because while there is some unconscious racism still around, true racists are seen as radicals and one of the evils best left in the pages of history. But write a story about abortion.

I did that one time. And honestly, I didn’t know it was going to illustrate abortion until I came to the end of it and it became obvious that’s what it was. So I went with it. In that future world, abortion was looked at as evil as we see racism now. The story was rejected because as one of the submission editor’s said, “I felt like I’d been hit over the head with a hammer.” If that same story had somehow illustrated racism was bad, I doubt it would have elicited that response. Might have even been accepted and praised as a very meaningful piece.

I don’t fault them for that response, however. Reading over the story, it didn’t look like the theme had arisen from the story. It looked like I’d written the story with the full intention of making a statement on abortion. But I didn’t. It organically rose from the story and the world I’d built.

Back to your point. I think someone who allows a theme to organically arise with the goal to tell a compelling story can be just as deep, and in the end, intentional. After all, we do edit our books. As a theme arises, we can latch onto it in later books. Which I’ve done with both series. The last book tends to really intentionally focus on the theme(s) in the previous books.

So maybe it isn’t a matter of intentional themes, but recognizing themes and developing them within the story.

Okay, I’ve rambled on long enough. What do you think?

I thought perhaps Mike and I were thinking along the same lines when I read his post, but after his last comment to me, I’m back to thinking we’re on different pages. Be that as it may, it will be interesting to see where God takes us.

About intentional themes, Rick, you said

Amen and amen! I think there hasn’t been enough instruction about how writers go about countering “preachy” without losing intentionality. It takes skill and hard work. A writer needs to believe in it and work at it to make it happen.

That some authors are satisfied that some theme, any theme, will appear in their fiction means, it probably hasn’t been given the attention it deserves. It hasn’t been thoughtfully woven into the fabric of the story.

When I said “shallow,” I meant that the things we believe and sort of take for granted are probably the ones that emerge if we’re not being intentional. These are probably themes that most people, Christians and non-Christians, hold in common.

I agree with you, though, that a writer can go back in a revision and develop a theme that they notice. It’s the way a seat-of-the-pants writer works, as I understand it. Character, plot, all of it eventually emerge–they find the story, so I can see that they also could find the theme.

I don’t look at that as all that different from the planning work I do before I start writing a manuscript. It doesn’t really matter when the intentional part comes about, I don’t think–before the first draft, after the first draft–at some point the writer needs to work that thread into places in the story instead of “front loading” or “back loading” it in a pile of preachiness.

The thing about Christianity–it is known well enough that people think they see it and think they’re trying to be converted as soon as a Christian shows up in the pages. I recently read a review of Jill Williamson’s Captives at Goodreads, and the person said she would have given it a 5 instead of a 4 but it was so intolerant because it only showed Christian people. Such an odd remark. The story shows one community with a strict, paternal structure that alienated some of the younger generation and another community that was a benevolent oligarchy without any moral code. I don’t think “Christian” ever came up in the whole novel. You could tell that the patriarchal community had Christian underpinnings, if you knew about Christianity at all, but it wasn’t a utopia by any means. It wasn’t depicted as “this is the right way.” So “intolerant”? Only because that’s what the reviewer things of Christianity, I’m guessing. But that was a big aside. Sorry!

Becky

I don’t think you can really interact with postmodernism if all you’re doing is outlining your plans to debunk it. The opposite of relativism isn’t Christianity, it’s the traditional sense of order, with the neatly lined boxes. I wonder if people don’t tend to conflate their religion with their sense of order to the extent that their sense of order IS their religion.

Just play with the ideas without an agenda. Postmodernism IS pretty much playing with ideas without much/any of an agenda. It pretty much only has meaning to the individual who experiences it, but literature takes great pains to capture the individual’s experience.

I just might have to write that story myself.

Notleia, I lost my response to you last night, so both of us are having computer woes to keep us from continuing this discussion! 😮

In my post, I named a handful of things that I believe have cropped up via postmodern thought which make it more difficult for a non-Christian to hear the simple gospel message Paul laid out in 1 Cor. 15:3-4–Christ died for our sins and rose from the dead. Someone who doesn’t think Christ was an actual historical figure isn’t ready to hear this answer. Someone who doesn’t believe he sins isn’t ready to hear this answer. Someone who thinks when we are dead that’s the end of life, isn’t ready to hear this answer. In other words, as with any other philosophy that contains components contrary to Scripture, it’s imperative for Christians today to understand the framework in which those around us are operating if we want to speak to them. For fiction writers, we also have the best way of challenging these premises that are in contradiction to reality–through story, which postmodernism understands and values.

Becky

And you’re still not really engaging with Postmodernism.

I’m not trying to engage with Postmodernism, notleia. I’m trying to inspire fiction writers to see beyond what so many have believed is what Christian fiction must have because it is the most important factor for this life and beyond–the gospel. I’m saying, contemporary thinking, influenced by postmodernism, has many people unprepared to hear the simple gospel. Writers who are aware of this can do something else in their fiction, something that can initiate thought about subjects that put barriers before people, keeping them from hearing the plain truth.

I’m sorry I wasn’t clear about my intent in this post.

Becky

Now I’m confused. What is commonly labeled “postmodernism” does include some unique truths, but it’s truths that SpecFaith’s regular contributors and most readers already believe — e.g., that experience informs worldview, that life is more than mechanical logic and neatly ordered categories, but also includes narrative and culture and imagination, etc. Speaking for myself, I’m quite comfortable with those things and how they’re based not in “postmodern” notions, but Scripture itself. Systematic theology, categories, and such can be helpful, but yes, they’re not the sum total of Christianity. To the extent that beliefs categorized “postmodernism” help us rediscover that, they’re helpful, but after that let us be done with the label and its associated (and ironically systematic) emphasis on anti-Biblical absurdities. There is only so much we can do to say “away with categories and boxes and arrogant certainty” without ending up trying to categorize and box up and become arrogantly certain that all labeled “postmodernism” has all the answers about how there are no sure answers. ‘Tis better to rely on God’s lovingly revealed Word about such things.

I agree with you, but I’m cautious about knee-jerk reactions against perceived postmodernist semantics. For instance, I think God could be said to be the ultimate Mystery, even though mystery is not all that He is, since He has revealed Himself to us in ways that are sufficient for our purposes. Postmodern ideologies clearly get a lot wrong, but almost everything wrong about postmodernism can be spun to illuminate an aspect of real truth. At any rate, we shouldn’t fight Postmodernism by trying to go back to old Modernist rationality or even the religious nominalism that existed before that. We should present the truth through great storytelling the best that we are able (and as readers and critics, see the truth even in works that try to deny it), irrespective of the latest cultural fads.

That probably sounds like an opinionated argument, but it’s really not. I agree with this post, almost 100%. I just differ in emphasis, I think.

Bainespal, thanks for bringing up this issue about mystery. It’s one of my little bugaboos, I guess.

I think a lot of evangelicals, or maybe Christians of all stripes, have picked up on the word “mystery,” but it’s not something the Bible teaches about God. It does teach His transcendence, but that’s not the same as unknown or unknowable. Because God is transcendent, we couldn’t know Him unless He chose to reveal Himself. Since He did, in fact, choose to do so, He is eminently knowable.

“Mystery” in the thinking of postmodernism applies to God because there is no absolute, because language can only be known within its context. We can seek God, catch glimpses of him as we perceive him to be, but we won’t know him–or so the postmodern philosophy prescribes.

But I agree with you as far as picking modernism over postmodernism as a philosophy for life. Both have strengths and both have weaknesses. As my former pastor said when I asked him what he thought about postmodernism, we are to live Biblically, not tied to any particular human framework. Makes sense to me.

Becky

My browser crashed, so I don’t know if my comment got posted or not, so here goes again.

It’s not really going to work if your interaction with postmodernism is just to debunk it. The opposite of Christianity isn’t relativism, it’s the traditional sense of order. The neatly lined boxes. Then again, some people’s sense of order is so conflated with their religion that it’s more like their religion is their sense of order.

Just play with the ideas without an agenda. Postmodernism IS pretty much the play of ideas without much/any of an agenda. It may not have much meaning outside the individual’s experience, but a great deal of literature is the capture of the individual experience. Use Deism if it helps.

I began writing a story from one image with an overwhelming sense of awe and peace, but it ended up having a strong sense of the Holy Spirit, which was definitely nothing I set out to write.