What Constitutes “Derivative”?

Due to the common use of the same textual sources employed by Tolkien and [Richard] Wagner there are a large list of close parallels between The Lord of the Rings and the Der Ring des Nibelungen. Several critics have made the assumption that the novel was directly derived from Richard Wagner’s operas.

Despite the similarities of his work to the Volsunga saga and the Nibelungenlied, which were the basis for Richard Wagner’s opera series, Tolkien dismissed critics’ direct comparisons to Wagner, telling his publisher, ‘Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases.’ According to Humphrey Carpenter’s biography of Tolkien, the author held Wagner’s interpretation of the relevant Germanic myths in contempt.

In the contrary sense, some critics hold that Tolkien’s work borrows so liberally from Wagner that Tolkien’s work exists in the shadow of Wagner’s.

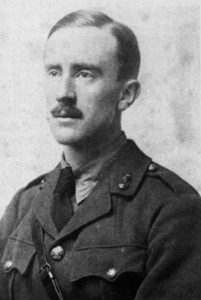

J.R.R. Tolkien, derivative? So those critics claimed.

I find that to be thoroughly ironic because the great accusation against writers of high fantasy today is that their work is derivative, a mere shadow of, you guessed it, J.R.R. Tolkien.

While Tolkien denied taking his ideas from Wagner, he did not hesitant to mention others who influenced him such as William Morris, H. Rider Haggard’s novel She, and S. R. Crockett’s historical novel The Black Douglas.

So what’s the difference between derivative work and that which has come under the influence of another?

Whether Tolkien mentioned it or not, his work bears clear markings of Finnish, Anglo-Saxon, and Norse mythology. Some think there’s even a dose of Celtic mythology, though Tolkien claimed a distaste for those works.

But “derived”? Only the similarities to Wagner seem to have stirred this accusation?

Maybe the easiest way to come at this would be to identify what did not illicit the derivative accusation.

1. Including mythical creatures such as elves and dwarfs.

2. A fictive world pitting good versus evil.

3. Similarities between Hobbits and the “table high” characters in Edward Wyke-Smith’s work.

4. Monsters apparently influenced by such works as Beowulf.

5. A paraphrased Anglo-Saxon poem as an illustration of the poetry of one people group in Tolkien’s fantasy world.

6. An adapted Shakespearean scene.

7. Intentional imitation of Morris’s prose, style, and approach.

8. Borrowed setting elements such as Mirkwood and the Dead Marshes.

If none of these earned Tolkien the accusation of derivative, what then, qualifies as such?

the accusation that a work is derivative seems to be leveled at fantasy more than at stories in other genres. When was the last time, for instance, that you heard someone criticize a romance for being derivative? Never mind that category romances, for years, followed a strict structure that was taught as necessary for the success of a novel.

I suppose, rather than “derivative” these works are considered formulaic, but didn’t they derive from one original work that contained the elements that have since become requisite to romance?

Still, I find it odd that fantasy similarly can’t fall into an easy formula and be acceptable, despite Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Rather, fantasy that cuts too close to an established work is labeled derivative, and this accusation is the kiss of death. It’s a wonder that Lord of the Rings became so successful once the derivative accusation began to swirl around Tolkien.

What exactly was it that brought the criticism, since it wasn’t setting, imaginative creatures, plot points, people groups, poetry, names, prose or style?

I suggest, in the case of Lord of the Rings, critics saw similarities with the central premise in Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen:

The plot revolves around a magic ring that grants the power to rule the world

– Wikipedia

Add to this that the ring was cursed, enslaving whoever would possess it, and you have strikingly similar central plot points. Discussion swirls around the idea that the similarities exist because Tolkien and Wagner drew from the same influences. Yet some scholars cling to the belief that Tolkien knowingly “borrowed” Wagner’s core concept.

Interestingly, some fantasy is intentionally derivative. I think of Bryan Davis’s Raising Dragons derives intentionally from the legend of King Arthur and Stephen Lawhead’s King Raven Trilogy from the Robin Hood myth. However, both, in unique ways, twist familiar stories in such a way that they become unique.

Interestingly, some fantasy is intentionally derivative. I think of Bryan Davis’s Raising Dragons derives intentionally from the legend of King Arthur and Stephen Lawhead’s King Raven Trilogy from the Robin Hood myth. However, both, in unique ways, twist familiar stories in such a way that they become unique.

The accusation of “derivative” is not used in such instances. Instead, it seems to be reserved for works that either model themselves after another work (which is what Christopher Paolini seems to be accused of) or those that utilize someone else’s unique development (science fiction that employs Star Trek technology and lingo, for instance).

In some cases, it seems as if critics are simply weary of stories with tropes such as good versus evil, at least ones that represent good as good and evil as evil. Normally bad vampires, as good seem to be all the rage, but then the Twilight books are hardly high fantasy.

I guess my point is this: the accusation of “derivative” has been around since Tolkien first made fantasy literature a thing of its own. Does the mere suggestion that a story is similar to some other source mean it does not have merit? I think millions of Lord of the Ring readers would say otherwise.

First posted at A Christian Worldview of Fiction November 2009

I always thought that Tolkien set out to give England a proper mythology, since its own is a hodgepodge of stuff from warring cultures that never settled down, like other civilizations did. So he took bits of stuff from other myths.

Wagner isn’t the only storyteller with a magic ring. I’ve run across other stories with them (although the titles escape me). Magic trinkets are fantasy standard. Just because Wagner and Tolkien used the same tropes doesn’t mean one copied the other. They probably drew on the same source material. The critics don’t seem to have thought of that.

I always thought “derivative” meant “copied directly from”, whereas there’s also this thing called “paying tribute”, which C.S. Lewis did with That Hideous Strength, including all of Tolkien’s Numinor lore. “Paying tribute” goes on all the time in the entertainment industry, from quoting popular lines to doing the Safety Dance or Rickrolling something.

Eregon is extremely derivative. My sister and I read it with our noses wrinkled as we picked out exactly who he had copied at what point. Kid becomes a Dragonrider of Pern with one of Pern’s psychic dragons, fights evil Orcs from Lord of the Rings, and has Obi-Wan Kenobi/Gandalf as a mentor, who then dies. He didn’t even bother to try to give each trope his own personal spin.

NetRaptor, yes, I think I read somewhere that one of Tolkien’s desires was to create England’s own myth. I think he succeeded quite well! 😀

You’re right about the ring not being exclusive to Wagner, which makes the criticisms of Tolkien ludicrous. Then there’s the whole idea that the first person to use an element, character, or device, somehow owns it and no one else can use it. I mean, if one artist in some genre at some time uses an object, can no other artist for all time use that same object? That’s ludicrous too.

As I’ve thought about this more, I’ve landed on a word in the Oxford English Dictionary definition of derivative: imitation. I think the difference between what Tolkien did in making use of Celtic lore and what Paolini did in copying the tropes of other speculative fiction is tied up in the way each used the works that came before.

I agree, there’s also an intentional nod to another writer–an element or name that others who know and love that work will recognize.

I guess my big complaint is that some people sort of automatically think a story with a sword or a castle or elves is derivative. No, just like Tolkien used a ring similar to Wagner’s and was not derivative, so stories today can use tropes Tolkien used, and not be derivative.

Becky

Thanks for this article! You raise a very interesting question, since I know for myself I like how Tolkien weaves so much of the older lore into his works–it’s fun to read Beowulf and see Meduseld’s similarities to Heorot, for example. At the same time, I would probably (and in some cases have) put down other authors for borrowing from Tolkien in a similar way. Do you think it makes a difference that Tolkien was using older and less-known sources at the time? (Not counting Wagner, of course.)

Audrey, Tolkien did lean upon Celtic lore, so you make a good point–his source material, if you will, went so far back it wasn’t on the radar screen of his contemporaries reading his stories.

Even today, knowing that he gleaned from old stories, we don’t generally think of that as derivative.

Perhaps the key is that he wasn’t imitating them, but using them. There is a difference between the two, I think, though many who throw around the “derivative” accusation seem to be oblivious to it.

Becky

Becky–

Thought you might be interested in this Tolkien-related article over at Blue Zoo Writers: “Six Writing Tips from J.R.R. Tolkien“. It’s not about derivatives, but it’s good writing advice.

Thanks, Keanan, I’ll definitely take a look at that article. I love discussions about Tolkien and his work. 😀

Becky

I have come to the conclusion that literature is in conversation with itself, through authors, over generations, and cultures, and centuries.

Sherwood, what an interesting take on the subject. It makes a lot of sense–one author responding to (i. e. Phillip Pullman to C. S. Lewis) or mirroring another (all those considered derivative).

And of course those who don’t write fiction aren’t party to these choices. Although I think the fact that so many people want to write fiction shows that we want to enter into the conversation.

Becky

But those who don’t write fiction get to decide who gets accused of being derivative, and who gets upheld as a great writer, and who simply gets ignored. Non-writers interpret the conversation, or comment on it, maybe the way a reader comments on a blog that he or she doesn’t write for. And we non-writers don’t always interpret or comment fairly. 😉

Ha! Good point! 😆

But interrupting or commenting is part of the conversation, as is getting to decide who’s great and who to ignore. There’s more than one way to get an opinion across, yes?

Becky