Speculative Fiction Writer’s Guide to War–part 1, Reasons

Today I’m launching a new series. (Or maybe I ought to say, “I’m harnessing my regular writing slot for Speculative Faith to motivate myself to write a book that’s been on my mind for years.” 🙂 ) My goal is to make a comprehensive guide to warfare, from beginning to end, from fantasy war based in the legendary past, to futuristic science fiction conflict. And we’ll start at the beginning–reasons. Why does anybody go to war in the first place? What causes conflict? And how do you use that knowledge to write a better story?

When discussing causes of human behavior in general, you’ll find that there’s much speculation and disagreement–and the subject of war is no exception to that. It’s not even universally agreed upon if war is natural to human beings. For almost all known societies over the entire world throughout all of known human history, at least on occasion wars are fought and at least a little formal training for warfare exists. Though it is also true that human beings in general show signs of having a natural aversion to killing one another–if we did not have such an aversion, training warriors to fight would not be necessary.

In terms of why wars begin, the Wikipedia article on war fairly represents the topic when it lists seven major categories of theories of reasons wars begin (Psychoanalytic, Evolutionary, Economic, Marxist, Demographic, Rationalist, and Political Science), many of which have sub-categories. In other words, there’s a lot of disagreement about this topic.

This Writer’s Guide for Speculative Fiction authors (which is focused on science fiction and fantasy) takes the view that warfare among human beings stems from aspects of human nature that are common to all human societies, but which require certain societal elements to exist before they can be expressed in warfare. In spite of occasional allegations of completely peaceful societies, there has never been a human society which has no concept of crime in general and murder in particular. Murder–in which one human being kills another for reasons the society does not see as valid–is very rare in some societies, but exists everywhere human beings live. Likewise, even in societies that practice sharing of resources, it still happens that people disagree over who gets what at what time on occasion, leading to conflict. Even in tribal societies that are very egalitarian, at times there is disagreement or even conflict about who will be in charge of a particular action. And even in tribal societies without a formal law code, it’s true that sometimes fighting occurs within the group over perceived injustice–usually relating to issues of crime, yes, but fighting can also erupt when a group of human beings cannot agree about what is and is not just or fair or right.

Murder, fighting over resources, fighting over position in a society, and disagreement over the rules can each be phrased in terms of a human trait that is the primary cause of each of these actions. While hatred is not be the only cause of murder, it’s a major one. While it may be possible to fight over resources without greed or envy, feelings of at least envy usually accompany such a fight. Seeking prominence over others is usually (fairly) associated with pride, and disagreement over the rules appeals to the innate human sense of justice. Hatred, envy (or greed), pride, and justice–all human societies express these traits to some degree or other. Note that the first three of these traits are generally seen as vices–and justice itself can be a vice, if misapplied.

Though not all human societies go to war, even if all societies have the traits that cause war. But even societies that don’t go to war, if they were invaded by others, would be able to define what’s happening based on the principles they already know. That’s true even if they are shocked by the level of brutality involved. For example: “Those people are murdering us to take our water!”

In speculative fiction contexts, it may be that fantasy races or alien species literally would have no concept of war and wouldn’t have any conflict within their societies either. Such people probably would not even realize they should run away when attacked, not immediately anyway. But in discussing warfare, let’s start with the baseline reasons of what is known about human beings first and then afterwards adapt that to non-human societies.

So if the reasons behind human conflict are found in all human societies, why is it that not all societies actually go to war?

The societies that don’t go to war fall into two groups: 1) tribal societies that occupy a niche in which war is unlikely 2) deliberately pacifist societies that come out of warlike societies and which consciously reject war.

The number 2 societies probably require the least explanation. They usually are part of a religious order that teaches that all human being are valuable, so killing any of them is wrong (think Amish or Mennonites or groups like them, or various monastic orders, or Jainists)–or on occasion are non-religious organizations that have high intellectual ideals that include rejection of violence (like some Israeli Kibbutzim). People raised in these societies who are taught to believe war is wrong usually live up to their beliefs and refuse to go to war.

Number 1 societies include tribes that are so geographically isolated that it’s very hard for them to make contact with other groups, let alone fight them. It also includes groups that occupy an ecological niche that other groups are not interested in. Example for both: Imagine a tribe living in a small oasis in a desert which is surrounded by well-watered lands–it may be that other tribes prefer to fight one another over the well-watered lands rather than cross the desert, leaving the oasis tribe to live in peace.

Note the existence of isolated groups that do not engage in warfare at all is the reason some anthropologists argue war is not natural to human beings. They imagine that the original state of the human race consisted of this type of isolated tribes that did not ever fight each other–only later when, say, agriculture was developed, could a society have surplus food to pay people to train for warfare full-time.

While it is true that desperately poor societies cannot afford to pay for a warrior caste, some tribal groups have existed in which everyone (or in most cases, every male) in the tribe was a warrior. That has been especially true for groups that live in areas that make for easy travelling and which have resources which are easily stolen (think the animals that pastoral nomads keep). These groups are usually the among the most warlike of all human beings.

So it seems there’s an element of necessity in who is and who is not warlike. Those who are vulnerable to attack are more likely to be aggressive (in self-defense) but the issue of resources also raises its head here.

Fighting over resources, whether water or food or even gold for societies that use precious metals, seems to be the primary reason for people to go to war. To either take or defend what they perceive they need. Humans also seem show a preference for not fighting over resources if they don’t have to–that is, societies which are vulnerable to loss of resources organize themselves to defend those resources, but ones who can obtain what they want or need “for free,” are much more peaceful–which is where the natural aversion to killing others seems to come into play. It does seem to be true that while some individuals may chose to kill (in the criminal sense) in any society, only societies who perceive they need train themselves in warfare actually do so. And that perceived need is mainly based on access to resources–though again note that almost all humans, historically speaking, have perceived a need to organize to protect resources, so this isn’t anything unusual. A pacifistic society is much more exceptional than a warlike one.

Note that while hatred of others may cause one person to kill another within a tribe and relates to a reason for warfare, it’s actually not usually the main cause of a war–but it can be an important catalyst. Especially because human beings are very quick to define other humans in terms of those who are part of our “in-group” and those who are part of an “out-group” (quotations are there because these are standard terms, though not necessarily ones I prefer). Humans find it much easier to hate someone who is not part of the in-group. When humans start thinking of the out-group as being less than human, which may not be limited to but certainly involves hating them, it becomes easier to go to war against them. Hating another human being to the degree that they are thought of as less than human, or another group of human beings, helps overcome the natural aversion to killing them.

Some people would elevate the fact humans divide into groups easily as a major cause of warfare. This tribalism in modern form can bleed over into racism and extreme nationalism, which certainly have been involved in many wars. While I agree that tribalism is important, that’s because we humans find it easier to hate those outside the tribe than those in it–tribalism itself is not the issue as much as hatred is. Without hatred and the willingness to kill empowered by hatred, tribalism or nationalism is mostly harmless–they amount to trivial things like which flag you wave at the Olympics.

Note that envy over resources in an environment in which conditions are harsh can easily become greed, in which one or both sides of a fight actually have enough to survive, but are striving for more anyway, hoarding gold like legendary dragons. Greed is a major cause of warfare–one nation or tribe seeking to take from another something it may not really need, but definitely wants. Think of Cortez’s conquest of the Aztecs, or even more so, Pizarro and the Inca, in which lust for gold, land, and women drove the Spanish conquest forward.

Pride (or prestige) as a motivation for warfare is a bit more complex. Societies that develop a warrior class usually laud praise on their warriors–and rightly so under many circumstances. They are, after all, protecting the in-group, and providing for resources people either need to survive or don’t need but want anyway.

There’s quite a bit to be gained in being a successful warrior in terms of how well others treat you. Certainly Cortez and Pizarro not only were greedy for gold, they knew in the warlike society of Spain, they would be admired as conquerors. They’d be given prestigious titles–they’d be seen as heroes (and they were then, though not anymore). Those who like to put things in evolutionary terms say the prestige successful warriors gain gives them the opportunity to produce more children, which they see as a basic drive. While it is certainly true that the prestige warriors have heaped upon them may help them marry and reproduce, the historic warriors who have reproduced the most did not have women flock to them because of their prestige as much as they took the women they wanted because of their desire to have them (greed/lust)–think Genghis Khan.

While it is sometimes true that a warrior caste will seek to go to war because of the prestige or honor involved (honor is how they’d put it), going to war simply because they can (like Klingon warriors) is actually not as common as fighting over resources. But having a warrior caste with intrinsic reasons to fight can certainly be a catalyst for a war.

Fighting for justice is not often listed as a reason for warfare by experts on the topic, but should be. When we think of wars of religion, weren’t people fighting because they think their religion is right (just) and the other religion (or lack of religion) is unjust? When revolutions happen, such as the French or American Revolutions, wasn’t part of the fighting taking place over perceived injustices and abuses? Like taxation without representation? Or anger at the abuses caused by the so-called divine right of a monarch?

Note that a sense of justice can be a catalyst for warfare in a different way that other traits listed here. People want to think of themselves as being in the right and it is much easier to defend violence that is perceived to be honorable than to do so for other reasons. Please recognize that’s true even if you assume there is such a thing as just war (and I believe there is). The existence of just war does not mean that every single appeal to justice is actually fair or true.

Often nations have a stated reason for war that’s different from their actual reason. The stated reason for the Crusades was that they were about justice–Muslims were heaping abuses on Christians in the Holy Land and furthermore had no right to be there as far as the Crusaders were concerned. Yet the actual reasons had a lot to do with overpopulated European territories, looking for lands (and resources) elsewhere, a warrior caste in Europe itching to go war (for the prestige involved), and the fact it was easy to see the Muslims as an “out-group,” not only because they were perceived as racially different, but more importantly because they did not share the Crusaders’ religion.

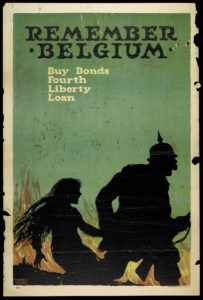

This WWI poster is about “The Rape of Belgium”

The “real” causes of the Crusades has been debated widely and will continue to be debated. Even if we grant that the Crusades really were about perceived injustice (a.k.a. a war of religion), it’s ridiculous to think Cortes and Pizarro invaded the Aztec and Inca Empires in order to right the wrongs those empires perpetuated, including their perceived errors of religion. Yes, the consquistadores probably felt better about themselves bringing priests along to justify some of their actions in the rhetoric of spreading their faith (which they would see as undoing injustice)–but their greed for gold, land, and women is well-documented as their primary motivation.

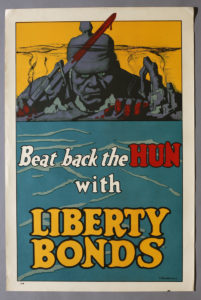

To leap to a much more recent example, did the United States really enter World War I “to make the world safe for democracy” (as US President Wilson stated)? Well, partially–the motives were to protect American shipping and businesses, but also there was a sense of justice involved, especially over widely-reported German abuses in Belgium (called in the press at the time, “the Rape of Belgium“). And also important was a wave of anti-German hysteria that swept through America–hatred of the other, the Germans, our enemies, the “Huns” as seen in the classic poster. (Note the imagery of the “Hun” is of a savage, barbaric invader from the East.)

“Hun” = German

You’d find if you dug into details that there were layers of motivations for the entire country, the basic causes interacting in a complex way. And also that the motives for going to war for a single soldier varied a great deal from soldier to soldier in that conflict–which would be likewise true for almost every war. Motives probably even varied for the same individual soldier at different moments.

And while the reasons for a nation going to war are more complicated than those of a single soldier in that nations often primarily seek to gain what they want by negotiation and only go to war when negotiations break down (as reflected in the war theorist Carl von Clauswitz saying, “war is the continuation of politics by other means”), the same basic reasons apply to all wars, even when political factors not named in this post are also involved (such as a nation overestimating its ability to win a war).

I’d say there are four basic causes of wars, listed in order of actual importance for most conflicts (though the order does in fact vary from war to war and person to person as mentioned above):

- Resources (or as a vice, greed/envy)

- Tribalism (as a vice, hatred of other groups)

- Prestige (pride)

- Justice (as a vice, false justice or religious extremism)

In order of stated importance, publicly declared importance, reasons for war are usually:

- Justice (nations usually proclaim themselves to be right–and only on occasion actually are)

- Prestige (calls to service and self-sacrifice are common, especially in modern wars)

- Tribalism–hating the other (though some wars have used so much propaganda against enemies that hateful tribalism or nationalism is openly more important than number three)

- Resources/greed (most societies talk least about their actual reasons, which are usually-but-not-always about possession of territory or other material things)

As you apply these principles to stories, think about how these motivations play out for the individual human beings involved, which may or may not be the same as collective national or tribal reasons to fight. Note that stated reasons for war are often different from actual reasons. Writing a complex mix of motivations for a war makes for a more realistic and more interesting story.

To briefly mention how to apply these principles to races or species who are not human, while it might be interesting to attempt to invent reasons for warfare that have no connection to how human beings behave, it’s probably best to simply change the order/priority of war reasons that also apply to humans. It will seem more realistic (to human readers anyway 😉 ) but can still provide some interesting twists.

What if, for example, other species always stated their actual reasons for war openly? Or if a fantasy race had a much stronger sense of justice than human beings have so they don’t ever care in the slightest about resources they could gain? Or if a race had no tendency to be tribal, but still fought for other reasons? Or if they had no actual aversion to warfare in the first place? Or on the other hand, what if a non-human society were naturally non-violent because of an inability to hate others (which is not necessarily the same thing as being good and pure in every way), yet learned over time it was necessary to defend themselves, taking much more time to process what war is than humans require?

Please excuse the length of this post, I’ll strive to keep future ones shorter, but I hope you’ve found it informative. With so many academic opinions on this subject, I don’t imagine for a moment that everyone will agree with what I’ve listed here. So what are your thoughts on the reasons why people go to war?

When it comes to conflict, there’s probably a sense of escalation that tends to happen. Let’s say person A caught a deer. Their neighbor, person B from the neighboring tribe, demands that person A give up some of the deer. The exchange can be civil at first, the A saying no a few times before taking on an angrier tone. B gets frustrated, and reaches for the deer to hack off a piece. A lashes out to keep B away. B is angry and strikes back. They fight and struggle until one dies.

That can be applied to more modern situations as well. Two people, or even nations, might not set out with the intention to hurt each other, but it happens over the natural course of two sides having interests that clash. Both sides get angry, or are unwilling to give in, so the only recourse is to fight until one side is incapacitated.

It is also interesting to note how human conflict compares to many(though not nearly all) animal conflicts. When conflict comes, at least between members of the same species, animals might prefer to use threat displays, or short contests to compare strength. In those cases, the weaker one typically runs off before grievous injury occurs. This is because actual fights are risky, and wild animals can’t get medical care. So if they know they aren’t going to win, they’d rather avoid the risk and find a way to obtain their desires through less dangerous means.

Now and then this might apply to humans, since we might try to warn or negotiate before fighting. But could you imagine two countries in real life avoiding war merely by having two athletes face off in a contest? Humans place a lot of importance on the things they are willing to fight for. If they want something bad enough, be it land or resources or freedom, they aren’t going to accept the results of a petty contest.

In my current WIP, one reason fighting happens within a particular area of the world is that the residents of that area consider fighting and hardship to be necessary to have a worthwhile life, to give beings the ability to adapt and survive, etc. Their philosophy is a bit complicated, but that’s why they purposefully live in a war torn area. They usually still have reasons for attacking each other, though, like the reasons you mentioned.

Autumn, one of the major views of causes of warfare (what we can call the “Political Science” view) is that war is essentially caused by a breakdown in negotiations leading to escalating hostilities and eventually conflict. The example you give is a basic version of that happening.

While I agree that breakdowns in negotiations often happen in warfare, I would say they are not primary. The reason why they aren’t is some wars have started with no negotiation at all–the launch of a surprise attack driving for taking whatever the goal of the war is. Yes, breakdowns of negotiations happen–not only in wars, but in personal situations that can escalate into murder. But even though an escalation is common, as is a breakdown in negotiations, are they essential to conflict? Again I say “no.” What is essential? What are they essentially fighting FOR in your example?

In your example, the deer. A resource. The conflict over the deer isn’t the fault of the slain animal itself–it stems from the fact both parties long to have the deer. Envy or greed or some other emotion motivates them to prize the deer so much it’s worth killing over.

They might also fight because of a sense of justice. Example: “Hey, you shot that deer on the hunting ground that MY tribe uses!” “Yes, but I shot it, so it’s still mine.” People often at least appeal to justice when disagreeing with one another (and sometimes they really mean it).

The sense of justice comes out especially in the terms of their debate over who gets the deer. And appeasing the other person’s sense of a “fair deal” (which I’d say is justice in the economic arena) is how a negotiation can successfully avoid a conflict.

Yes, it is true that risk to self is a reason most parties try negotiation first before straight-out attacking. Though I will make the case in another post there is another reason–humans empathize with other humans to the degree that killing another person up close is usually very traumatic for the killer. So yes, humans usually attempt to negotiate first and only fight after an escalation.

But I still don’t think negotiations going downhill leading to escalating anger are primary causes of warfare. Though there are very common and perhaps I should have said more about them.

Yeah, I definitely don’t think it’s the only/primary cause. I brought those things up earlier as factors and details, not necessarily primary causes.

Personally I think war is usually caused by a combination of things, and the particular combination will depend on the situation. Sheesh, it might even depend on the person one asks. Now days, the decision to go to war is made by groups of people on both sides. Each politician or whatever might have slightly different motivations for saying ‘Yeah, let’s attack them.’

Have you seen Naruto, Naruto Shippuden, and Fate Zero? Their takes on war and conflict are very interesting.

I’m sorry but I have actually seen relatively few Japanese-produced movies or series. The ones I have seen are mostly Gundam based–I especially liked 0083 Stardust Memory and 0080, War in the Pocket. Have you seen those? (Their view of warfare embraced both heroic and tragic aspects.)

You realize that means we have to spam you with suggestions until you become as otaku as we are, right?

Noob’s first anime: Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood (is on Netflix). Brotherhood is the adaptation that didn’t outrun the manga and therefore has a coherent story. Also the dub is A+

Like, all of Studio Ghibli’s works, but my personal picks are: Laputa: Castle in the Sky (considered a seminal steampunk piece in Japan), Princess Mononoke (pretty good dub, SO PRETTY ANIMATION). Those are distributed by Disney so there’s a good chance you can find them to rent at a library (or maybe thru inter-library loan).

Also one more military-oriented is “Space Blazers.” They remade it in 2016(?) so it looks slightly less egregiously 70s. The real Japanese name is “Space Battleship Yamato 2199.” It’s on the streaming site Crunchyroll, but it may or may not have a dub (I watch it in subs).

Actually haven’t seen a lot of those yet XD

What do you tend to like/dislike as far as anime genre goes, notleia? A lot of my faves have probably been classified as shounen and I guess seinen. Now and then I watch some shoujo stuff too though.

I’m pretty tired of shounen, TBH. Right now most of what I’m watching is moe trash with high school girls and slice-of-life and not much plot but okay for junky decompression watching. Seinen’s generally okay, every once in awhile I’ll watch a shoujo.

I’ve been trying to catch some of the well-known older works, but it’s very much dependent on what I feel like watching.

Eh, yeah. Haven’t been keeping up with a lot of the newer shounen releases, but from what I’ve seen some of them haven’t been all that great. Haven’t really had time to watch a lot of new anime, though. There’s several on Netflix of various genres I might want to try later, though.

Have you seen Wolf’s Rain? Not sure what genre it’s in, but it’s an older show, and it’s one of the few anime I like watching the dubbed version of. Haven’t seen it in ages, but it was one of my first anime.

I’ve been watching Kakuriyo: Bed and Breakfast For Spirits lately as well. It’s sort of in the same vein as the happy fluffy decompression idea you expressed.

Totally on top of Kakuriyo. Still think she should’ve taken up Matsuba-sama up on his offer to take her to Mt Shumon so she’d have to deal with at least 90% less bullcrap that the plot keeps throwing at her. On the flip side, there would be 90% less plot.

Have watched Wolf’s Rain, but I’d like it better if I could ever find the OVA with the ending. I think they miscast Crispin Freeman, tho.

I don’t think I even knew there was an OVA, so all I really saw was a glimpse of them in the rebirthed world.

I’m just here to gush about FMA: Brotherhood and the “whole new world” it introduced to me, namely, manga/anime, when I watched it for the first time this January. ?

I mean, I knew from what I’d heard about that whole world that once I let myself enter it, I’d love it, but it also…. was ….. so…. nerdy.

Well, it’s happened, and I’m in now. ?

ONE OF US ONE OF US ONE OF US

I second that.

Welcome to your new nakama, Jo.

Haven’t seen those. Not much of a mecha fan usually, though I might watch them some day.

To quickly summarize, the warfare in Naruto/Naruto Shippuden is often depicted as a cycle of hatred. So revenge and loss and loneliness are big themes there. There’s a lot of sub themes in there as well, such as political corruption(which has a lot to do with the plotlines surrounding the Uchiha clan.) It’s very interesting since the show basically follows the struggle to attain long lasting peace. Once the show gets into the origins of Konoha, (the village the main character is from), that theme is felt very strongly. Before Konoha’s formation, ninja clans fought each other constantly, even sending little six year olds out to fight and die. Average life expectancy was around thirty for the lucky ones.

But then Konoha is built, and children weren’t sent into combat until around twelve, and it was something people from that generation would have seen as a blessing. But then as future generations suffer, they see twelve year olds sent into combat as a tragedy, and want to get rid of war and conflict so no one has to fight anymore.

Fate Zero is rather dark and complicated, and almost seems nihilistic on the surface. The main character, a jaded assassin named Kiritsugu, is fighting for the Holy Grail so he can end all conflict in the world. The entire show is basically a small scale war, with the characters fighting for their own goals, hurting others and suffering in the process. The heroic and tragic aspects of war are explored heavily in this show as well, so maybe it’s like Gundam in that way. There’s still some hope and happiness in the show too, though, like with Alexander and Waver’s plotline, or the very very last scene involving Kiritsugu.

0083 especially is not really about the mecha. It has them, but it’s about a lot more. I’d like to think you’d enjoy it.

I might give it a shot 🙂

If you do watch it, bear in mind that the first couple of episodes are not the best of the bunch.

I started two of the Fate series on Netflix (Fate/Stay Night, and another one that I don’t remember, but what I read about it said it was an alternate history, but still connected to the Holy Grail War.)

But I haven’t tried Fate/Zero – which is also on Nf, apparently. I just added that one to my list… ?

I’ve only seen Fate Zero, the new Fate Stay series (Unlimited Blade Works I think) and maybe one or two episodes of Apocrypha. Fate Zero’s probably the best and most well written thus far, but it’s very dark. If you really pay attention to everything the chars are thinking and feeling, it can really put you through the emotional wringer.

And it’s so deep and complex that you have to watch it several times to truly appreciate it. There’s some great girl chars in there, too. Fate Zero’s one of those shows that can give a character lots of depth even when that char’s only in there for only one or two episodes worth of time.

There’s also Attack On Titan, though I haven’t seen nearly all of that show yet. I think their philosophy on war is going to be along the lines of human/political corruption and beings doing everything they can to survive against vicious threats, though. Yet another amazing show on my list of things to finish.

No fair Travis. You can’t write this book, because I have my outline of “War, and Things Like It: How To Write Better Conflicts From Skirmish to Campaign” well in the advanced draft stage for the same purpose! (Smiles) This is great. Writers need great resources like this!

Well, my fellow Travis 🙂 I happen to be open to collaboration. Perhaps we could merge our ideas into one book?

Perhaps you wouldn’t want to do that–but think about it anyway and let me know if you might be interested in a joint project.

It’s a big project writing a book like this–I certainly feel it could profit from perspective other than my own.

As a traditionally-published speculative fiction author who has also self-published a series of 10 novels based on the air war in the Pacific in 1941-42, I find this both compelling and fascinating, and to the extent that human war can be summarized briefly, you’ve done an excellent job. In an old Anthropology class, I studied New Guinea tribes that did not have war as we understand the topic. They would sometimes fight over arable land, but since they use slash-and-burn agriculture and move on once the land is spent, such actions seldom take place. It’s more about pride and women, but even then, deaths are rare. However, I think they are the exception, akin to your oasis example.

More to the point, few would think of Hitler as a man driven by religious fervor; yet he was savvy enough that the belt buckles worn by each German soldier in World War II read “Gott Mitt Uns” (God with us). Imagine that – Nazis thinking that God blessed their racist slaughter.

Thanks for this intro – I look forward to the other elements in your series.