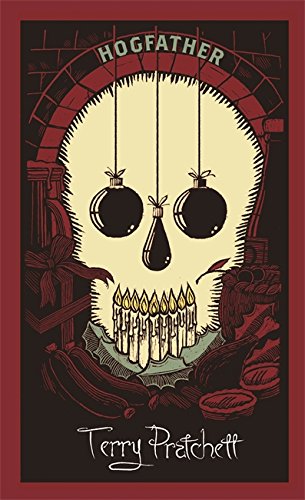

‘Hogfather’: In the End, a Discworld Story about Nothing

Several years ago I was introduced to Pratchett’s Discworld stories, and have usually enjoyed the ones I’ve read. In my own reading, Pratchett is unique in that he can very skillfully blend satirical elements with serious themes, giving the reader both reasons to chuckle and reasons to think.

Pratchett wrote some stand-alone Discworld books, but most of them follow one of a few different sets of characters. Hogfather‘s main characters are Death and characters connected with him, though Pratchett also brings in the wizards of Unseen University.

Summary

There are beings who want to destroy the Discworld, and they have the $3 million to make it happen. (Apparently, this was well before inflation, when $3 million could still be considered real money.) Meanwhile, the Assassin’s Guild has a member whose mind is so askew that he can find a way to assassinate a being whose existence is problematic: the Hogfather, the Discworld version of Santa Claus. So, Death has to keep belief in the Hogfather alive, while telling his granddaughter Susan to not get involved (and grandkids being grandkids, of course she goes right out and gets herself right involved).

Humor

Because this is a Pratchett story, of course he will fire all kinds of satirical shots. And of course the current commercialized state of Christmas can lend itself very well to such shots.

For example, there is the Hogfather (actually Death dressed up as the Hogfather) visiting the Maul, which is disruptive on all kinds of levels, not least of which is because this Hogfather thinks his job is to give kids the things they ask him for, including swords and ponies. This is a concern for parents (who want their children to have, well, toys) and to shop owners at the Maul (who want people to buy things, not have them given to them). And there are the Hogfather’s hogs (he doesn’t have reindeer pull his sled), who insist on acting like hogs, even in a maul, to the endless curiosity and delight of all the children.

Susan Sto Helit is one of the Discworld’s more fascinating characters. She is Death’s granddaugher, connected to him in ways genetics have no control over, and she lives in both the real world and in his world. In this book she’s a nanny, taking care of a couple of precocious children. One way she helps take care of them is to get rid of the monsters under their beds, in their closets, and in the basement, because she knows as well as the children that there really are monsters in those places. She takes no guff from those monsters, and she has a poker to make sure they give her no guff.

Humor?

With all the humor hits in this book, maybe it should be expected that there are some misses, too.

For some reason, Good King Wenceslas takes some jabs in one scene. The song is about the king giving some food and drink to a peasant he sees gathering wood. Pratchett makes this act into the king only wanting to be praised for his generosity, while not really being concerned at all for the peasant.

And even things Christian speculative fans may consider either sacred or near-sacred come in for some knocks. Among the sacred:

Death flicked the tiny scythe just as the bloom faded…

The omnipotent eyesight of various supernatural entities is often remarked upon. It is said they can see the fall of every sparrow.

And this may be true. But there is only one who is always there when it hits the ground. (42)

Sadly, Pratchett shanks this one, badly. It isn’t Death who is there when the sparrow falls to the ground.

Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? And not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father. But even the hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear not, therefore; you are of more value than many sparrows.1

And another one:

Goodwill to all men was a phrase coined by someone who hadn’t met Foul Ole Ron. (273)

Granted, Foul Ole Ron is a fictional character, but the ones who first sang the phrase “goodwill to all men” knew very well about people whose hearts were far darker than any fictional character’s, and they still sang of peace on earth and goodwill to all men. And they had reason to sing of those things, not because of man’s darkened hearts, but because of the one who was born that day in the City of David, Christ the Lord.

Among the near-sacred, there is a wardrobe that scares a man near to death, before seeming to consume the man to death, except his boots

“There are magic wardrobes,” said Violet nervously. “If you go into them, you come out in a magic land.”

Bilious looked at the boots again.

“Um…yes,” he said. (326)

I will simply say, those who create fantasy universes where flat worlds roam through the universe on the backs of elephants and turtles look silly when they try to mock magic wardrobes.

Serious matters

But the biggest problem with this book is its main message.

“All right,” said Susan. “I’m not stupid. You’re saying humans need…fantasies to make life bearable.”

REALLY? AS IF IT WAS SOME KIND OF PINK PILL? NO. HUMANS NEED FANTASY TO BE HUMAN. TO BE THE PLACE WHERE THE FALLING ANGEL MEETS THE RISING APE.

“Tooth fairies? Hogfathers? Little—”

YES. AS PRACTICE. YOU HAVE TO START OUT LEARNING TO BELIEVE THE LITTLE LIES.

“So we can believe the big ones?”

YES. JUSTICE. MERCY. DUTY. THAT SORT OF THING.

“They’re not the same at all!”

YOU THINK SO? THEN TAKE THE UNIVERSE AND GRIND IT DOWN TO THE FINEST POWDER AND SIEVE IT THROUGH THE FINEST SIEVE AND THEN SHOW ME ONE ATOM OF JUSTICE, ONE MOLECULE OF MERCY. AND YET—Death waved a hand. AND YET YOU ACT AS IF THERE IS SOME IDEAL ORDER IN THE WORLD, AS IF THERE IS SOME…SOME RIGHTNESS IN THE UNIVERSE BY WHICH IT MAY BE JUDGED. (pp. 380-381)

By the way, Death speaks in all-caps. So does Susan a few times, when she needs to. She’s Death’s granddauther, after all.

THERE IS A PLACE WHERE TWO GALAXIES HAVE BEEN COLLIDING FOR A MILLION YEARS, said Death, apropos of nothing. DON’T TRY TO TELL ME THAT’S RIGHT.

“Yes, but people don’t think about that,” said Susan. “Somewhere there was a bed…”

CORRECT. STARS EXPLODE, WORLDS COLLIDE, THERE’S HARDLY ANYWHERE IN THE UNIVERSE WHERE HUMANS CAN LIVE WITHOUT BEING FROZEN OR FRIED, AND YET YOU BELIEVE THAT A…A BED IS A NORMAL THING. IT IS THE MOST AMAZING TALENT.

“Talent?”

OH, YES. A VERY SPECIAL KIND OF STUPIDITY. YOU THINK THE WHOLE UNIVERSE IS INSIDE YOUR HEADS.

“You make us sound mad,” said Susan. A nice warm bed…

NO. YOU NEED TO BELIEVE IN THINGS THAT AREN’T TRUE. HOW ELSE CAN THEY BECOME? said Death, helping her up onto Binky. (381-382)

(Binky is Death’s horse.)

So many things could be said in response to these statements.

For example, the entire first chapter of Lewis’ Mere Christianity could be called to answer this charge about the non-reality of things like justice and mercy:

Now what interests me about all these remarks is that the man who makes them is not merely saying that the other man’s behaviour does not happen to please him. He is appealing to some kind of standard of behaviour which he expects the other man to know about. And the other man very seldom replies: ‘To hell with your standard.’ Nearly always he tries to make out that what he has been doing does not really go against the standard, or that if it does there is some special excuse. He pretends there is some special reason in this particular case why the person who took the seat first should not keep it, or that things were quite different when he was given the bit of orange, or that something has turned up which lets him off keeping his promise. It looks, in fact, very much as if both parties had in mind some kind of Law or Rule of fair play or decent behaviour or morality or whatever you like to call it, about which they really agreed. And they have. If they had not, they might, of course, fight like animals, but they could not quarrel in the human sense of the word.2

Death wishes to claim that somehow two galaxies colliding over millions of years is not right. But if he wants to say that justice and mercy are not realities, then he essentially undercuts his own statement. Without justice, what is right and wrong, just and unjust? Without justice, how can the collision of two galaxies be called “not right”?

And does believing lies really make them true? Do we really have to believe in the lies of justice and mercy, in order to make them become, to make them realities? Do we really need to believe in small lies, like tooth fairies and Santa Claus, so that we can then believe in big lies, like justice and mercy?

This is relativism writ large and ridiculous. If mankind is the creator of justice and mercy, if we create such lies by our beliefs in them, then these lies simply take on the forms we create them in, and since mankind would hardly be in unison about what those things would look like, they could and will look like anything. The lie of justice could look like trial by jury, and it could look like imprisonment without trial. The lie of mercy could look like giving medicine to the sick to help them live, and it could look like giving poison to the sick to help them die.

Pratchett, through the character of Death, gains nothing by calling these great virtues big lies, he merely loses everything. He loses the right to say that colliding galaxies are “not right”; he loses to right to have a truly just city guard; he loses the right to use his books to make social commentary; he loses the right even to write books, for he has no right to write about heroes and villains, for he has no standard by which he can tell us who is a hero and who is a villain, who should win and who should lose, or what the world should really be like.

But the great virtues are not big lies. We can appeal to justice, not because we have created the big lie of justice, but because there is a God who is just. A person can say that something is right or wrong because, whether he or she believes in it or not, there is an absolute standard, which man did not create, by which we can judge whether something was right or wrong.

Conclusion

There was plenty of humor in this story, and I had a good chuckle every now and again. And some of his satire was smart enough to smart. But, overall, the ideas this book puts forth are not all that good. I can’t give it a rousing recommendation.

I’m not making the connection between “playing with words and absurdities” = “somehow authorial moral failure.”

I interpreted Death’s comment on justice and mercy is that it’s not naturally occurring in the world, i.e., that it’s artificial. Are artificialities also lies? In some contexts, yes, that is the connotation.

Is it just a deepity? Perhaps. But people talking out their butts is not necessarily a moral failure. Heck, it may be one of the most common occurrences in existence, and while common =/= moral, the common does influence our sense of what is normal, and what is normal does influence what we think is fair, and isn’t societal justice largely based on our sense of fairness? Isn’t the struggle between the ideal of justice and its manifestation in the real world as societal justice what makes our culture change and sometimes advance?

Am I talking out of my butt? Is justice something we pull out of our butts? Are rhetorical questions pretentious?

But Lord help us if you ever discover Kurt Vonnegut. Do let us know if he’s allowed to write stories when narratives have beginnings and ends while his Tralfamadorians are supposed to exist outside time.

–I interpreted Death’s comment on justice and mercy is that it’s not naturally occurring in the world, i.e., that it’s artificial. Are artificialities also lies?

I interpret the comment as saying that justice and mercy and not realities, that they are simply concepts that man has made up, like tooth fairies and Santa Claus. It is only belief in them that gives them any kind of “reality”.

“AND YET YOU ACT AS IF THERE IS SOME IDEAL ORDER IN THE WORLD, AS IF THERE IS SOME…SOME RIGHTNESS IN THE UNIVERSE BY WHICH IT MAY BE JUDGED.” This “rightness in the universe” strikes me as being similar to what Lewis wrote about, that we do have the concept in our minds of a moral code, on by which we can measure our own actions, and those of other people. But Death, or Pratchett, holds up that idea as being false. I disagree.

Pratchett’s great gift was to tell stories where people behaved like we more or less expect people to behave, erratically and thoughtlessly, performing the comedies of errors that are everywhere in real life, then to pivot in the last chapter or three and reaffirm his belief or his hope that, okay, overall we’re dumb, but collectively we tend to arrive at just action just by trying all the bad options first–that the arc of history is long, and bends toward justice

what Pratchett is really doing is being conciliatory to not just religion but to stories in general. if you haven’t, you absolutely must read his book Only You Can Save Mankind, which is about this from first page to last. a boy is playing a video game in the early 90s; the alien ships surrender to him. he thinks it’s just a joke, but they start showing up in his dreams demanding safe conduct, and across the whole world stop appearing in the game, too. the question of whether it’s real stops mattering. if you dream of a person and they feel real, do you second-guess yourself? do you hurt them because you’re not sure?

Pratchett covered a lot of ideas in his time, but the central thesis he always came back to was that the stories you tell yourself, the dreams you have, are important, and there is -no check on whether they’re true or not.-

Terry was not down with religion. but he was recognizing the power of a story to have real meaning in a person’s life. he had an optimism in him that it would average out to match a kind of pragmatic, liberal justice, by the modern understanding. I’m not so sure, but his hope does buoy me up a little.

“why do dwarves think that they have no religion and no priests?” Sam Vimes would ask himself when he watched dwarven society, which really does seem like a religion to our eyes

“Tak did not ask that we think of him,” a grag once answered him. “he just asked that we think.”

you also left out the most important line from that sequence, which is an apt summary of this whole dumb post of mine:

“‘These mountains,’ said Susan, as the horse rose. ‘Are they real mountains, or some sort of shadows?’

YES.”