Feed The Right Wolf: ‘Tomorrowland’ and The Allure Of Fatalism

Peruse any antique bookstore or dated sci-fi periodical and you’ll find yourself confronting a conundrum: in the world of yesteryear, prior to the smartphone and the self-driving car, before even mankind’s ascent into orbit, the future was limitless and filled with wonder. Human colonies took root in the seabed and speckled the solar system, while new techniques of forestry and agriculture harnessed nature for our needs. We were ambitious, we were expansive. Technology was a toolbox without bottom, and we but journeymen in God’s great workshop, uncovering the uses of those implements He’d planted for us to find. No distance was too great, no challenge too immense. It was our destiny to overcome.

This was the world of Tom Swift and Gene Roddenberry, of The Jetsons and the World’s Fair. A world getting better all the time. A world drunk on hope.

That world is gone. And all the king’s smartphones and self-driving cars won’t put aplomb together again.

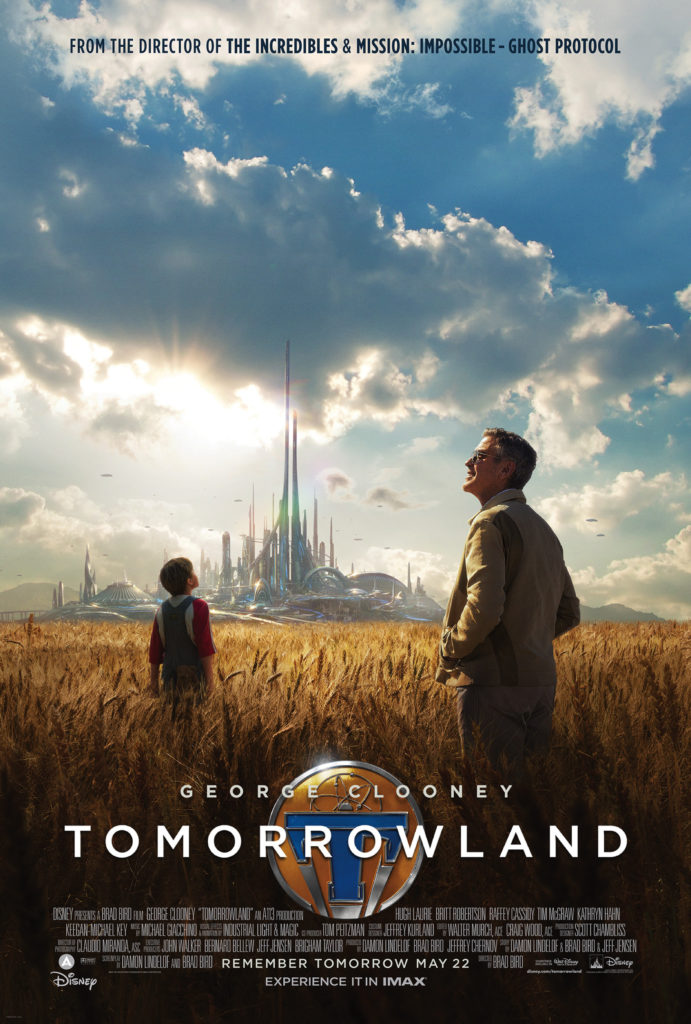

And yet to recover that galaxy far, far away is the self-appointed task of Tomorrowland, the latest film from virtuoso writer/director Brad Bird, he of Iron Giant and The Incredibles fame. It’s an ambition worthy of the plucky retro sci-fi to which the story pays homage, and, perhaps inevitably so, an ambition that appears futile in the face of modernism’s malignant malaise.

And yet. And yet what if …

What if.

Let me back up to the beginning. Tomorrowland begins when a young activist saboteur named Casey Newton, played with infectious enthusiasm by Britt Robertson, is presented with an invitation to a place that doesn’t exist. Awed by a virtual-reality utopia that materializes when she touches a pin, Casey sets out on a quest to discover the truth behind the illusion, picking up assassin-android pursuers and a mysterious, knowing girl who calls herself Athena (Raffey Cassidy) en route, and eventually, on a rain-lashed night way out in the sticks, winding up at the booby-trapped retreat of Frank Walker (George Clooney) a cynical recluse who’s visited utopia and returned, but not to tell the tale.

What Frank tells Casey instead is that the world’s ending. He’s seen the coming cataclysm in a machine he built on the other side — in Tomorrowland, a hidden realm for artists, engineers, and all who dream of a brighter future.

Needless to say, he didn’t stick around long.

What follows is a quest worthy of a ten-year-old’s daydream: a kind of Men in Black meets National Treasure. They’ve got to get back to Tomorrowland. Now the plot devices are flying thick and cryptic, and viewers who hate soft sci-fi won’t be mollified by all the lampshade-hanging, even though the cast clearly believes. The acting here is delectably good, by the way, what with Robertson throwing herself into her role while Clooney and Cassidy cultivate a compelling chemistry. But even so, the film still demands something that’s in short supply these days: a childlike sense of wonder. If yours has been seared by CGI and the Internet and the idea that “what’s real is dark,” I’m afraid you’ll find nothing here but cheese.

And yet, if you’re willing, Tomorrowland wants to reboot your imagination.

The mystery arc’s heating up now, but its resolution remains elusive. One of the things I’ve always admired about screenwriter Damon Lindelof is his ability to not answer questions. Where others would feel compelled to show their hand, Lindelof glories in the unknown. It’s a tendency that’s been known to backfire on him (Lost, Prometheus), but here it works like a dream. Tomorrowland is a slow-burning reveal — a magician who savors his setup, knowing it’ll only intensify the trick. What is Tomorrowland? Who is Athena, really, and what’s her relationship with Frank? Can Frank’s machine be trusted? Does any hope remain? These questions go unanswered till the end.

And yet it’s worth the wait. Why? I’m glad you asked. Spoilers ahead!

At its heart, Tomorrowland is a battle between competing philosophies. While everyone agrees that the world in its present state has a date with destruction, proposed solutions differ. The governor of Tomorrowland, a man named Nix (Hugh Laurie), has been broadcasting a premonition of impending doom for decades. It’s his firm belief that the only way to spur people to change is to play upon their fears. But fear has long since succumbed to acceptance, and now people gorge on dystopian fiction and set fire to their own neighborhoods, anticipating nothing in their future but chaos and death, convinced they have nothing left to lose.

Whenever young Casey used to feel overwhelmed by circumstances, her father would pose her a riddle: “Two wolves are always fighting. One is darkness and despair. The other is light and hope. The question is, which wolf wins?”

Nix thinks he knows. “All around you the coal mine canaries are dropping dead and you won’t take the hint! In every moment there’s a possibility for a better future, but you people won’t believe it. And because you won’t believe it, you won’t do what’s necessary to make it a reality. People don’t care about the future because it doesn’t cost them anything today! The future asks nothing of you. We saw the iceberg and we warned the Titanic. But you sailed anyway because you want to sink.”

Ouch.

Wait, are we still in a Disney film? And we’re actually acknowledging the failure of modernism? What happened to following your heart and wishing upon a star? And isn’t this Nix guy supposed to be the villain? So why do I find myself nodding in agreement as he points the finger at me? By respecting my agency, he’s condemned me to despair. For what can man do against his own kind’s total depravity?

Which wolf wins? “The one you feed.”

As Nix’s barb is driven home, Casey Newton explodes. “You’re feeding the wrong wolf!” she cries, and then the battle is joined.

And there I sit, stunned by my own indecision. Is Nix right in his assessment, or is Casey? Is it naive to expect more from people than shortsighted selfishness, or is such doomsaying a self-fulfilling prophecy? How much of a difference does what we tell ourselves really make? Is it better to focus on harsh realities or potential glories? Is the former a kind of resignation, or is the latter just wishful thinking?

I think you can guess which side of this issue the film comes down on, but the fact that it confronts the question at all left me agape. Nor is the solution easy: it requires real sacrifice to put a stop to Nix, real commitment. Ironically, our heroes are fighting as much against death as for life. Their response to fear is far from apathetic — but it’s only because they see light, not darkness, at the end of time’s tunnel.

Tomorrowland is more than the narrativization of a Disneyland attraction, more than a nostalgic romp through the dreams of yesteryear, or an excuse for Damon Lindelof to toy with viewers’ patience. It’s even more than an environmentalist call to action, though it contains such overtures. At its core, it’s a confrontation of the fear and apathy that’s gripped the American pop imagination since the seventies, and a plea for refocus. Things don’t have to be this way, it says. Fatalism grows because you feed it. Stop feeding it. Then, someday, just maybe, we’ll enter the land of promise, the land of Tomorrow.

As Christians, we know we’ll never arrive in Tomorrow until Christ reigns on New Earth. But this film does make me wonder. How much farther might we go, if only we reached for the stars?

I’d say that wheat is mystical because it’s successfully a monoculture. Look at that stuff. No rye, no cheat. Mystical Wheat probably gets good test weights, too.

Yes! If only people were a monoculture, too. But no, instead we have to have Matthew 13:24-30. *grumblemutter*

Those old science fiction books were optimistic because they had no idea of what they were talking about. They thought technology was magic, and that all they had to do was take the inventions of today and push them through to the future by renaming them. A rifle would be an electric rifle and a motorcar would be an atomic motorcar. Going to the moon would be like a long boat trip. You can live on Venus. Essentially they were daydreams, and they faded when the future showed to be not like the present at all. This happens in the negative too though; reading William Gibson’s Neuromancer is even more dated than 50’s SF.

Tomorrowland sounds interesting, but this is a deep argument and I think the movie will be simplistic. I think you’ve convinced me to watch it, though.

I don’t think anyone is believing, or suggesting, that we really by now ought to have jetpacks and moon cities, and because we don’t then someone is to blame.

Instead it’s an overall criticism of our society’s growing cynicism toward all these.

We’re not as often using scientific progressive as a symbolic stand-in for, well, victory and paradise. (The Christian would want to limit these to symbol-only anyway.) Instead we see “science” as a means to our own flippant entertainment, “secular” legalism, or else, as Tomorrowland warns, our own shrink-wrapped version of a “fun” apocalypse.

Modernism’s enthusiasm didn’t peter out because the future didn’t turn out like the present; it petered out because the future ended up looking exactly like the present, but with more conveniences. Turns out all that education and affluence and infastructure and SCIENCE(!!) didn’t do a dang thing to improve the base nature of man. I think that’s when the excitement began to wane: when people realized that technological advancement didn’t equate to moral advancement. And without that sense of Manifest Destiny to motivate us, conquering the universe just looked like so much work.

I don’t mean to say people are angry about the lack of those things. It’s more that the kind of scientific optimism/better future through tech mindset as found in science fiction relied more on possibility than realism. As we live through some incredible technological revolutions, we’ve seen how it plays out in reality. It might be cynicism or it might just be acknowledging complexity.

The idea of a christian idea of science…maybe we need our own Tomorrowland. Our own novel about those themes.

As a movie, I thought Tomorrowland was a stinker. So many things that just didn’t work.

As far as acting goes, the only one that manages passable grades is Cassidy (Athena). I don’t fault Clooney or the the rest of the cast, I fault the script and the director.

Slow first half, but not because the movie didn’t try. The script simply changes the story halfway through and then a third of the way through.

The movie starts out about a misunderstood genius girl on the run, but half-way through it turns into some burned-out old guy having romantic tension with an android that still looks like a twelve-year old (BTW-that was just creepy). The last third becomes a story about rescuing some Utopia. Any three of these would have worked as a reasonable movie plot (except the 12 year-old and the old guy- creepy).

This is a movie that simply tries to do too much, then can’t focus, and simply falls short by the third act.

Thematically? Well, everyone is too cynical and we need to return to the past, but wait, we can’t, so lets try a new future. I was bored and uninspired.