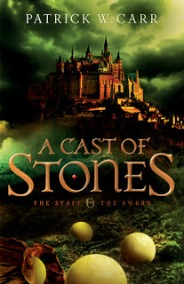

‘A Cast Of Stones,’ A Clash Of Tones

A Cast of Stones stumbles out of the gate with an ungainliness not dissimilar to that exhibited by its protagonist, a young drunk whose grand entrance consists of a muddy faceplant outside the entrance to a tavern. That’s not to say it’s immediately off-putting; from the very first page, it’s apparent that this novel, a debut high fantasy by author Patrick Carr, harbors lofty aspirations. It begins in medias res. It’s conscious of its own setting and makes a concerted effort to convey that setting to the reader. Its characters talk like real people. It cares about atmosphere and mood and all the subtleties which function, invisibly, to elevate prose into an art-form and cause us to feel that which we absorb from a page.

A Cast of Stones stumbles out of the gate with an ungainliness not dissimilar to that exhibited by its protagonist, a young drunk whose grand entrance consists of a muddy faceplant outside the entrance to a tavern. That’s not to say it’s immediately off-putting; from the very first page, it’s apparent that this novel, a debut high fantasy by author Patrick Carr, harbors lofty aspirations. It begins in medias res. It’s conscious of its own setting and makes a concerted effort to convey that setting to the reader. Its characters talk like real people. It cares about atmosphere and mood and all the subtleties which function, invisibly, to elevate prose into an art-form and cause us to feel that which we absorb from a page.

But it tries too hard — grasping a little too tightly at sophisticated-sounding language while neglecting a deeper issue: the fact that the reader has been given absolutely no reason to care about what happens. The protagonist, Errol Stone, is, as has been noted, a drunk. That in itself isn’t a problem; I’m actually quite impressed that a Christian author would choose to shackle his hero with such a high-profile, in-your-face character flaw. What’s a problem is the fact that he’s only a drunk. He has no redeeming qualities, no admirable traits. Everything he does, he does in order to lay his hands on yet another mug of ale. What’s even worse than this two-dimensionality is the fact that he likes it. He has no dreams, no vision, no goal in life. His only wish is to remain in a pathetic state of dependency deplored by the reader. He isn’t interesting in the slightest. He makes you want to put the book down and move on.

Keep reading.

It soon becomes apparent that Errol Stone is embroiled entirely against his will in a fracas of far-reaching repercussions. He’s contracted to deliver a mysterious parcel to a mysteriously reclusive priest, then fired upon by mysterious hit-men en route. Upon reaching his destination, Errol Stone discovers that things are even more mysterious than he’d thought. The priest, Pater Martin, and his companion Luis appear to be more than they seem (yes, that’s kinda redundant, but it’s what we’ve gotta settle for when the POV character isn’t interested in the plot). In the ensuing chapters we’re treated to cryptic, half-overheard conversations, much futile pitying of Errol the Addict, eye-bugging sentences like “Luis snorted a catarrhal sound that reverberated in his throat,” and the amazing fact that Pater Martin never rises from a seated position without “levering his bulk.” Errol himself is, of course, almost completely oblivious to all this; he’s a passive peon complacent in his squalor. Things have been set in motion by Errol’s coming — momentous things — but Errol himself remains as stagnant as ever. You can glimpse the shadow of a larger story coalescing in your peripheral vision. You just wish the protagonist would get with the program already.

Don’t give up.

It turns out that Luis is a Reader, an officer in the story-world’s powerful Catholic-analogous Church who accesses knowledge and foretells the future by casting lots. Readers are born, not made, and Luis quickly identifies a similar talent in Errol. This is such a big deal that Luis deems it necessary to dispense with Errol’s personal liberty and put a Compulsion on him — a magical directive which will ensure he shows up under his own power at the Conclave, a council of Readers in the distant capital city tasked with choosing a replacement for the heirless King of Illustra. And thus begins a journey as comfortably familiar to high-fantasy fans as are the stereotypically black-clad assassins dogging our heroes’ steps. But now Errol’s reticence seems even more selfish, since more than his own welfare is finally at stake. Fortunately, you’re now nearing the novel’s 25% mark.

That’s your goal. 25%.

As the first act draws to a close, the story begins to change because Errol begins to change. Events are set in motion which forcibly separate him from both his companions and his continuous influx of ale. Purged of his flaw, Errol becomes a different person altogether: an interesting person. In fact, he now demonstrates such a refreshing proclivity to soak up instruction that you almost forgive the author for conveniently depositing him in the lap of The World’s Most Awesome Mentor Figure Ever, a mysterious farmer who, for little apparent reason and without incurring any apparent opportunity-cost in his day-job, takes Errol under his wing and turns him into a master of the quarterstaff. At this point the story dips dangerously close to a cringe-worthy “I know kung-fu!” moment, but the author manages to cram in just enough thwacks and bruises to make the whole thing feel marginally real.

And by this point it’s too late to stop reading, because we’re out of the doldrums and running before the wind, sails high. Patrick Carr has finally found his stride as a writer, and, buoyed by a protagonist we now actually respect, A Cast of Stones keeps picking up speed until its remaining flaws and hiccups flash past like the whistling ends of Errol’s staff as he ascends the merit-based ranks of a company of caravan-guards. I’m grinning now, because the stuff I’m reading is just as engaging as the very best offered by the secular fantasy market. The supporting cast feels distinct and complex — their schemes are well-motivated, their dialog seamlessly natural. The story just flows. It has purpose, direction. And combat. Lots of combat.

A word about the combat: I love it. Though it’s light on technical description (due, I’m guessing, to the author’s inexperience with medieval weaponry), it never feels either dull or unrealistically melodramatic. Carr knows when to skip past an event whose outcome you’ve already guessed, and he knows how to draw out the tension of a genuinely frightening encounter. And, though Errol may be a quick study, a lazy prodigy he is not. His sweat-drenched ardor to improve his newfound abilities is nothing short of inspiring. It leaves one wondering if he really could get so good so fast …

And all the while the Conclave is looming, growing in Errol’s thoughts. He’s been destined against his will to walk right into a real hornets’ nest of a third act in which the savage wayside and bawdy common-room give way to the haunted halls of a city besieged from within by an unknown enemy. A place where secrets will come to light and fates will be decided.

A Cast of Stones fulfills many of my long-held wishes for quality “Christian fantasy”: it pays attention to its syntax and occasionally engages in original metaphor, develops a confident sense of pacing which leaves the reader no room for tedium, features an innovative magic system complete with rules and limitations, demonstrates self-awareness by lampshading its cheesier moments, feels no obligation to strike a moralizing tone, and consistently cultivates genuine tension. It’s a glittering gem in its subgenre, well worth your time and effort. Its latter three quarters constitute a very good novel.

But it falls short of greatness.

Why is this? What prevents this good novel, this entertaining novel, from finding a place beside genre giants like The Way of Kings and The Name of the Wind? Before flipping the first page I had skimmed several unfavorable reviews which complained of Carr’s supposedly shallow worldbuilding or his story’s grievous lack of a flyleaf map, but now, having finished the book, I don’t believe such critiques to be substantive. Carr’s style lends itself to the material; at no point did I feel contextually malnourished. Not every high fantasy requires reams of cultural or geographical description. Carr doesn’t describe things before they become relevant to Errol, and his restraint in parcelling out information makes for compelling mystery-arcs. No, the novel’s limitations have little to do with its worldbuilding.

But as I digested the story over the ensuing weeks, I realized that it was limited. It had failed to move me, to pierce my soul in any meaningful way. I wasn’t mulling over its insights or grappling with its themes. Ultimately, it wasn’t a tale which would stick with me for longer than it’d take me to finish the next book in my queue. But why?

The answer lies in the relationship between the story’s internal and external conflicts. Specifically, in the fact that the two exhibit no discernible relationship whatsoever.

Here’s what I mean. Throughout the first act, Errol’s internal conflict — his alcoholism — dominates everything, drowning out nearly all hints of the upcoming external conflict with the forces threatening the kingdom. Those hints which do manage to penetrate Errol’s ale-addled brain seem disjointed and irrelevant. After all, who has time to care about the fate of the world when you know your protagonist doesn’t stand a chance of survival unless he sobers up? It’s what irritated me so badly about the story’s first quarter: the only thing I wanted was for Errol Stone to transmogrify into someone I actually liked. The internal conflict was the only thing that mattered.

But then Errol quits his drink cold-turkey, just in time to man up for the plot’s demands. And that’s that. It’s over. At no point during the remainder of the novel does he suffer a relapse. Sure, there’s token gestures to temptation, but nothing which actually influences the plot, nothing which informs the external conflict. It soon becomes apparent that, even though an abusive priest has alienated him from organized religion, Errol possesses a highly-developed and totally unmotivated sense of honor which precludes his willingness to cast lots for profit, among other things. Errol Stone has traded one form of conflict — the kind that pitted him against himself — for a more superficially interesting variety dealt with via whirling lengths of ash. It’s like the whole first act didn’t even matter. And ironically, the moment at which I began enjoying the novel was the same moment it threw away its shot at saying something profound about existence.

If the conflict within Errol and that without had been blended, if the two had somehow been linked, what a realm of thematic possibilities would have opened before this story! No longer would Errol’s alcoholism have been a mere impediment to be shrugged off before the real plot could begin, and no longer would the real plot — the entertaining plot filled with adventure and intrigue — have felt as empty as it did in retrospect. I imagine a decision to explore the consequences of addiction in a high-states environment would have been a difficult one for any author to make. What’s more, the results would have likely proven unpleasant at times for readers. I don’t fault Carr for forgoing that route. But I must therefore question his decision to make Errol an alcoholic in the first place. Why burden the guy with such a distinctive vice only to whisk it away when push came to shove? It seems meaningless, as though Carr simply sat down in front of Errol’s character profile, noticed a blank checkbox labeled “Primary Flaw” and obligatorily decided to fill it in with something nonstandard.

Don’t get me wrong: this fundamental disconnect doesn’t ruin the story by a long shot. But greatness is all about meaning, and meaning isn’t easy to achieve. Like the answer on a Reader-carved lot, it becomes visible only after innumerable pares of the knife, each as careful and precise as all those that came before. When the sculpting finally ceases, not a stray particle remains to mar the internal cohesiveness of the work.

A Cast of Stones, though shaped from sturdy stuff, could use a few more turns.

I had dismissed the book for that very reason. Now, maybe I’ll have to read it some day.

Your conclusion about Errol’s flaw is interesting. I appreciate that Carr was trying to portray a genuinely flawed hero, somewhere beneath the stereotypical knight-in-shining-armor on the Hero/Anti-Hero scale. Even if it didn’t really work, I’m glad that even “clean” Christian fantasy is up to making the effort.

I just hope that Errol’s rehab doesn’t correspond to a salvation analogue. I viscerally dislike Total Transformation themes in Christian fiction. Even if it doesn’t involve any kind of conversion or spiritual revival, there’s a potential for some truly uncomfortable analogies to the Christian life. Especially if you’re giving this book to Christian children.

At any rate, great review!

I didn’t feel that Errol’s rehab was tied to any kind of conversion message. In fact, a point in the story’s favor is that it doesn’t contain such a message at all — merely the implication that Errol’s assumptions about life may be flawed. As a character, he’s allowed to reject and resent the story-world’s Church without getting preached at by the narrator (by other characters, sure, but not by the narrator). And, by association with Errol, I as a reader feel free to make my own judgements and draw my own conclusions about the story’s entities and institutions. That’s a very good thing.

But just ’cause Errol’s transformation was emotional, psychological, and chemical rather than spiritual in nature doesn’t mean it was realistic. That’s because it was contained within that relatively brief section of the story set aside for what I can only describe as a protagonist swap, in which the flawed, unlikable Errol morphs into the clean, competent Errol before getting on with the narrative.

As a writer, I am both frightened and awed by this review. 🙂 Wow! Nice work, Austin.

Thanks, Kerry! That means a lot, coming from the likes of you.

I’ll post my own review over this book in a few days, Austin. I have some specific areas of disagreement with what you said here. The first is that I immediately found Errol to be engaging. I said in my review that I didn’t know how Patrick Carr pulled that off, but I’ve thought about that some more. I did feel his humiliation in the opening scene. I didn’t know that anyone should be treated the way he was. That was immediately followed up by a scene that showed he had a skill surpassing that of anyone else in the community. In other words, he wasn’t worthless or no good, even though he was a drunk. That was immediately followed by the scene in which he’s been targeted by an assassin. Well! Now I know there’s more to this character.

And yes, he still thinks only about getting back to the pub, but when he needs to step in and act heroically to save lives, he does that. All this happens in the first 25% of the book! Errol may not have a goal other than get his next drink, but clearly he’s got more going for him than that, and I want to find out what it is.

I also remember one person who reviewed this book saying that Errol’s reaction to drink after he dried out was very true to life. I thought it was believable. He handled it primarily by staying away from it, but that doesn’t mean it became a non-issue for him. Not at all.

I was one who was critical of the worldbuilding, not because it didn’t feel fully developed. It did. But it lacked the typical fantasy accoutrements–the map, glossary, character list–that help readers of a series keep the world straight. This is a big cast, and it grows bigger; a big world and it expands further. I think the need for those extras grows as the series progresses.

I guess readers will have to determine which side of these various points they fall.

Becky

And now I see I already posted my review here at SpecFaith.

Becky

I agree with Rebecca. I somehow liked Errol and felt sympathy for him even though his actions were a mess. I think part of the reason he still had a conscience was that it’s almost too cliche to show the drunk who doesn’t care about anything but the bottle. Errol’s drinking was taking him down that path, but until someone forced him to stop, he couldn’t be bothered to take anything else seriously–an attitude that can be seen in many people, drunk or sober.

I’d add too, that the man who cared for Errol and mentored him actually became a father figure, and the lack of a father was the very reason he’d dived into the bottle in the first place (I don’t remember if this is revealed in the first book or in the one that follows, A Hero’s Lot). So, not only did someone stop him, but a significant someone who was a far better replacement for his escape mechanism.

Becky

Becky,

So why do you think Errol starts out as a drunk? I don’t mean in terms of character motivation — the story covers that fairly well. I mean in terms of broader thematic purpose. What purpose is served by Errol’s alcoholism, other than to preach to the reader that “alcoholism is bad”? Why did Patrick Carr choose to introduce us to a protagonist so pathetically helpless as to be incapable of engaging with the plot until entering, against his will, an entirely new state of existence?

First there’s Errol the Addict, annoying burden on everyone around him. Then that Errol falls into a river and gets swept away to the isolated abode of The World’s Most Awesome Mentor Figure Ever (father of The Token Girl Who Begs Our Hero for a Shirtless Scene, by the way), a man who literally beats the cravings out of him. When Errol arises from this convalescence — cleansed, empowered, and pretty much resurrected in every conceivable fashion — it’s as a different character: Errol the Hero. Not once does he suffer a relapse. Not once does his prior alcoholism influence the ensuing story one iota (other than bringing his adoring fans to tears at the thought of what a wretch he’d once been). Prior to Errol’s personality swap, we saw no hints of what he’d eventually become. After the swap, we see no hints of what he used to be. It’s as though Errol’s a perfect man who just happened to get tragically victimized by drink. Take away the drink, confront some childhood trauma, and everything’s all good now.

That sequence of events doesn’t feel real to me.

Is there a thematic purpose to Errol’s alcoholism larger than incidental moralism? If so, I don’t see it in A Cast of Stones. Is there something I’ve missed?

Why must there be a “broader thematic purpose” to Errol’s being a drunk, Austin? Why can’t there just be a logical character motivation revealed through the backstory? It completely works for me and is believable. And while he does struggle with drink as someone might who has been sober for years and years rather than for months, I think the change shows his deeper development–that he no longer has the need to escape life as he once did.

I don’t think the alcoholism in the story “preached” anything. I mean, no one lectured about the evils of alcohol that I recall. It’s pretty hard for a story to “preach” when all it does is show.

You asked:

I maintain that’s a mis-characterization of Errol. He wasn’t helpless–which was why he was given the job of carrying the message and communion supplies to the pater. Which was why he was able to escape the attempts on his life. Which was why he had the wherewithal to save the two men he was with from dying because of the poison they’d ingested. Clearly he was engaging with the plot.

Errol the drunk was never a burden on everyone. He had the sympathy of a good number of people who understood why he’d fallen. They knew the emotional blow he’d been dealt when he was orphaned before he reached manhood. They actually wanted to help him, though they didn’t know how.

Of course you’re right that “coincidence” plays a part in the story, considering who finds him washed up on the riverbank. Or not–considering the character of the person who would reach out to save a someone he doesn’t know who is at death’s door. Would an evil murderer or a fellow drunk or a cruel duke have given the inert body lying beside the river a second look? Would they have taken him in, nursed him back to health, then agreed to teach him (rather than simply use him as slave labor)? Of course not. The choice was either for good people to find him or for him to die.

I’ll argue, there was no personality swap. Errol had shown himself heroic before he got sober. More than once. He showed himself in need, too. And the father-figure who came into his life, gave him what the bottle could not. So why would he return to it? That’s not only not likely, it’s not good fiction. Readers don’t want to see a character deal over and over again with the same issue. They want to see growth and development. That’s in this book (and the next) in spades.

I’ll say again, I don’t think there was moralism involved in Errol’s being a drunk. I don’t think people in our society need to be convinced that alcoholism is a bad thing. It’s sort of an established given, as it was in Errol’s world. Even the people running the pub didn’t want Errol to be a drunk.

I also don’t agree with the idea that there has to be a thematic purpose for ever decision an author makes regarding character motivation or action or reaction. Errol’s choice to drink is believable given what his life was like and the traumatic event that orphaned him. Does it have to have some greater spiritual significance? I don’t think so. There’s plenty of spiritual significance in his hatred of church and the men of the cloth. I tend to think the spiritual themes are quite overt.

Becky

In a story, everything must serve a purpose. If it doesn’t, then it has no reason to exist on the page. This is the Law of Conservation of Detail, and it’s the only way that I as a writer can command a reader’s attention, conjure order out of chaos, or weave a sturdy story out of the fraying threads of everyday existence. Readers, being savvy, rightly expect this law to always be in effect at all times. Therefore, if I as a writer spend a quarter of my book focusing on a particularly annoying trait in my protagonist, only to dispel said trait from his life without his incurring any lingering consequences therefrom, my readers will be fully justified in wondering why, exactly, I bothered obsessing over said trait in the first place. That’s why I ask what thematic or narrative purpose is served by the alcoholism of Errol Stone.

I appreciate that you sympathize with Errol’s initial plight and respect him in spite of his flaws. I understand that the difference between our reactions thereto is likely due to personal taste more than anything else. (Although I completely disagree that Errol had “shown himself heroic before he got sober,” since he does nothing in the first 25% of the story that isn’t motivated by pure self-interest other than moving faster than he otherwise would’ve to a place he was already going in order to tell someone else that his friends needed help.) But regardless, my challenge still stands. Since the latter three-quarters of A Cast of Stones wouldn’t have changed one iota had its first quarter simply been absent, why was the first quarter even necessary?

Allowing ale-addled Errol to open this tale was a risky — perhaps even gutsy — move on the part of the author. It carried with it an inherent risk: that people like me would simply lose interest and walk away. I don’t make it a habit to read about people who don’t interest or inspire me in the slightest. And Errol didn’t. To be frank, the only reason I kept on slogging to the one-quarter mark was because I’d promised you, Becky, that I’d go ahead and read the book on your recommendation. Ultimately I didn’t end up regretting that resolution, but this shouldn’t cloud the fact that the novel utterly failed to hook me on its own accord. And it didn’t have to be that way. If the author had opted to ditch the idea of Errol as an alcoholic, then I’d have been engaged from the get-go.

So my question, again, is this: why was it worth the risk? What does Errol’s alcoholism add to the plot that, if removed, would render the whole structure unstable? Why is it necessary? Why is it important? (Other than to deliver to the reader the message that “alcoholism is bad”?)

And this brings us to my point about greatness. The reason I picked up A Cast of Stones in the first place is because I happened to be grousing about the lack of truly great Christian spec-fic post-Tolkien, and its title was proffered to me as worthy of such an adjective. The reason I don’t consider it a great novel — good, yes, but not great — is because, for a narrative issue of such plot-stifling magnitude as Errol’s alcoholism, there’s no apparent justification, no apparent greater purpose. It doesn’t even feel real. It feels forced upon the story from outside.

Why doesn’t Errol have a relapse or two? Why don’t we get to see him struggle — really struggle, not just get his hand rapped by The World’s Most Awesome Mentor Figure Ever until he stops reaching for a bottle — with the fallout from his neigh-lifelong habit during the ensuing months chronicled by the narrative? Why isn’t he tempted? Why don’t his adversaries use his weakness against him in some meaningful way? Why is he suddenly this goody-two-shoes prodigy when he’d be so much more interesting as a conflicted character? Why isn’t his addiction put to good storytelling use? For the first quarter of the story his problem as a character is that he isn’t even slightly conflicted about his lust for liquor, and, for the remainder of the story, his problem’s that he entertains no doubts about his abstinence therefrom. It seems it’s either one or the other with Errol: he’s either a pathetic pariah or a shining example.

But both realism and relatability lie between those two extremes.

Austin, honestly I’m not trying to be irritating here, but I think I already answered all your questions. First, Errol’s inebriated state IS NECESSARY, but not for some theological purpose it seems you want to impose on every element in the novel. It is necessary for character development, which is at the heart of good story telling.

I’m sorry you missed the diamond in the rough which I saw Errol to be. I thought of another thing which made me like him–he was likeable to the other characters in the book. All except the priest who beat him. And there was another reason this character, drunk though he was, engaged me: he was mistreated. For no apparent reason. But he didn’t become murderous in response.

The fact that he saved the two priests’ lives certainly was heroic, especially in the face of his attitude toward clerics in general. He had made it clear he didn’t want to go with them. What he wanted was to get back to the friendly confines of the pub. He had the chance to do this as they lay dying. The herb woman didn’t even hold out much hope that the priests had survived, but Errol acted selflessly and led her back to them. He also stood against the assassin, not once but multiple times, and attempted to lead the attack away from the others. But I suspect, having not cared for him from the beginning, these things were not noteworthy in your estimation. They were for me. It’s what we’ll have to chalk up as the differences between the way people read.

As to the subject of relapse and the idea that this is the only way you would see the character as really struggling with his drink, I’ll reiterate my points: 1) not all alcoholics fall off the wagon; 2) readers don’t want to see characters deal with the same issues over and over–they want to see growth and change. In my estimation, that’s what we got–not some magic transformation but a believable, though truncated, process (and you seem to have missed the scenes where he in fact had an internal struggle with drink, showing he did doubt); 3) his state of drunkenness or his choice to escape his problems via alcohol is secondary to his choice to escape. Once his REASON for escape was gone (he thought), his need to escape was gone as well. The story was never about Errol triumphing over drink, which is what you seem to think it was by your continued reference to a moralistic message that I never saw present.

Again, I don’t know if you’ve read The Hero’s Lot or not, and that second book in the story may be informing me of some of my views. I read the two one after the other, and don’t know what facts came out in the first and which in the second. It might be beneficial to keep reading the story. It’s a lot bigger than the alcohol. That was a device Errol used to medicate his pain. But his pain was always the real problem. And his pain is something he still needs to face.

So now I’m wondering if all this character development in an action fantasy series entitled the Staff & Sword is more what women readers care about than guys. Seems the story got interesting for you when the battles started coming. I enjoyed all the action too, but I certainly didn’t think seeing what Errol’s “normal” looked like was without purpose, uninteresting, or off-putting. I found Errol to be relatable from the start, and I found his changes to be believable.

So I guess we disagree. Which is all I was saying in my first comment. You gave your reaction to the book. I gave mine. Now it’s up to readers to see what they think.

Becky

Character development is essential, of course, for any character in any story. I just don’t think that Errol Stone’s development over the course of A Cast of Stones was particularly belivable or meaningful. Though I can’t speak for Hero’s Lot, the emotional trauma which incited Errol’s alcoholism was indeed revealed in Book One. But just ’cause I understand why Errol fell into drink (and that account I did find totally believable and compelling) doesn’t mean that I buy the means by which he escaped therefrom.

But it does appear that we’ll have to agree to disagree about this. And that’s okay — this is all part of a robust and healthy conversation about storytelling in general and this story in particular. 😉

On first blush that sounds like a statement about man’s deadness in sin to me.

But I haven’t yet finished the book. Alas for my old smartphone with Kindle on it, which suffered a cruel fate at the hands of a closed pocket and washing machine!

By the way, Becky may have already published her review. But I have not.

So there’s still hope for further conversation on this story. 😀 Which is excellent.

I certainly hope it wasn’t the author’s intention to make Errol’s alcoholism analogous to his deadness in sin, because that would give rise to some unfortunate implications. For instance, what would we be supposed to make of the fact that Errol doesn’t drink — doesn’t sin — even once following his “salvation”? How would we interpret the fact that his alcoholism was ultimately just a coping mechanism with which he mitigated the pain of a severe childhood trauma? And what would be our response to the idea that, for Errol, deadness in sin is a matter of morals — that “new life” is a function of just shaping up and getting it together?

No, I don’t think Errol’s alcoholism was intended as a sin-analogy, because the analogy swiftly falls apart. I think it was intended to be no more than it appears. But I still can’t figure out why it was necessary, or even useful, in either a narrative or a thematic sense.