Critical Race Theory has come to dominate how many modern people think about race and racism. I’ve mentioned this theory before, but have only offered a partial definition. Personal time doesn’t allow me a full explanation of the origins of Critical Race Theory (CRT), even though I think CRT is an important topic worthy of discussion. But it so happens that one of the founders of CRT, Derrick Bell, crafted a science fiction story called The Space Traders intended to illustrate the plight of black people in modern America. This post is a discussion of that science fiction short story and how its backstory stemmed from a number of the ideas central to CRT. And…by the way…we are finally on a subject that’s clearly on topic for Speculative Faith–science fiction!

Why Science Fiction?

The science fiction of Derrick Bell’s story isn’t particularly complex–the “science” element amounts to advanced aliens making an unusual proposal to the human race. Most of characters–well, all characters but one–are one-dimensional. Nor would I consider the story especially well-written. That’s not really surprising, because Derrick Bell was a law professor and not a science fiction writer.

But of course science fiction is the perfect medium for illustrating an idea. Science fiction has long been a means of social commentary by imagining counter-factual situations, such as: What if we are all in a computer simulation? (the Matrix) What if genetic fitness becomes the basis of a future society? (Gattaca) What if aliens invaded us in the same way we historically invaded colonial possessions? (the War of the Worlds) Etc.

As a short story, The Space Traders, first published in 1992, has been pretty successful. It’s been featured in several anthologies and was adapted for television once upon a time. (Here’s a link to the Wikipedia article on the story and also a link to the full text of the tale should you want to read it–it’s just shy of 12,000 words long). But again, I’d say that’s because of the controversial nature of the subject of the story, rather than it’s style. (Though on the other hand, it’s not a terrible story, either. The ending is pretty powerful.)

What the alien ship might have looked like. Image copyright: The Atlantic.

The Space Traders Summarized

The central character in The Space Traders is Gleason Golightly, a conservative black man who is an economic advisor to a white Republican president. As I’ve said, he’s the only character in the story with any depth. Though the story doesn’t begin with him.

The tale starts in a near-future scenario–from the point of view of the Nineties–in which aliens mysteriously arrive on January 1st and offer the United States unlimited clean energy and vast wealth–with a catch. All the aliens want is the USA to hand over every single person in the country who identifies as black. For purposes unknown.

The tale begins on 1 January and counts up until 17 January–which in the story world is a Martin Luther King Jr holiday…and also the day the United States ushers all black citizens into the alien ship cargo holds. Irony blatantly intended.

The story says the aliens adopt a voice like the former president Ronald Reagan, which causes all white people to trust them but causes suspision in all black people in America. I’ll comment on this further down.

Action leaps to the White House and of course the conservative cabinet is all for making this exchange. After all, in this story world, their conservative policies have wrecked the environment and bankrupt the country–they despirately need the alien technology and wealth to rescue the country from its dire straits. (I won’t comment on this further, but yeah this bit of story backdrop is more than a bit over-the-top-politically-liberal.)

But they want to hear from their token black economics advisor–the story directly calls him “token” (and mentions black people see this character as an “Uncle Tom”). The concerns of the cabinet being: “How can we sell this exchange to the public?” and “How can we justify our actions?” and “How can make this work legally?” rather than, you know, the ethics of the situation.

The story says directly that if the aliens had asked for any other sub-group of people, such as green-eyed red heads, the exchange would never have been considered for a moment. I’ll comment on this in a bit.

Golightly naturally doesn’t want the exchange to take place. The story from this point forth is about his efforts to first avert the exchange but when his efforts fall through, to save himself by escaping to Canada.

His strategy to derail the exchange is that he meets with a group of black Civil Rights leaders and attempts to persuade them they should speak out in favor of the trade. If they could only show that black people are in favor of the prospect of being hauled away by mysterious aliens, then white people would themselves wonder why black people were for it, which would be their best chance to save themselves. Because, you know, if black people want the exchange, white people won’t want to give it to them. Reverse psychology.

Golightly fails to persuade the black community leaders. They think his idea is crazy–but he despairs when they don’t listen to him.

To legally get rid of all blacks, the USA needs to enact a constitutional amendment in which the military draft is applied to black people. So all will be drafted into “service” for the good of the rest of the country. Bell mentions a few legal parallels to this, specifically stating the US Constitution itself sacrificed black people for the purpose of making the USA, so the idea the nation would do so again isn’t unthinkable.

The story spends a bit of time talking about the Liberal opposition to the amendment allowing the exchange. Part of New York City is shown to be shut down for a while due to protests led by Rabbi Abraham Specter, with the cooperation of many American Jews. The story says at one point what the Jewish motivaton is–they don’t want to be the ones stuck at the bottom of the social order to receive the full ire of angry poor whites. So they want black people to stay.

Other, non-Jewish Liberals are referred to in that thirty percent of the USA is said to be against the amendment, while seventy percent are for it. Note that the US population of African Americans is about eleven percent, so nineteen percent of the rest of America were against the exchange. The Jewish population of America is less than nineteen percent and I can’t imagine Bell missing this detail, so clearly other, non-Jewish Liberals also opposed “the Trade.” The story never says who were the other Liberals, but it does assign them a motivation: Guilt.

A scene from The Space Traders in the HBO special Cosmic Slop. Copyright HBO.

Golightly attempts to make the case early on with the cabinet that white people will be extremely afflicted with a sense of guilt after the fact if they trade off all black people for the alien tech. This doesn’t affect the cabinet, but as far as the story is concerned, guilt is the only motivator to want to help black people other than not wanting to be at the bottom of the social order yourself.

The aliens warn the United States government that they if they let black people escape to other countries, the deal will be off. The story references a few getting away, but the USA mostly blocking any escapes. The federal government promises to send a few prominent black people to other countries in exchange for their help, including Golightly and his wife, but they take back this offer in the end.

The second to last moment of the story features Golightly trying to escape to Canada but being caught by the US Secretary of the Interior, a colleague Golightly worked with and knew personally. His wife wondered if black people would have been worse off if Golightly had managed to block the legislation, because black people would be blamed for the country not receiving aliens’ benefits. The story basically leaves this comment hanging.

In the end, the aliens require all black people to strip down to a single article of clothing before boarding the ship. The story pointedly says they leave the United States in the same way their ancestors had arrived. As ship’s cargo.

The Space Traders Criticized

There’s much in this story I disagree with, but I can summarize all my objections in three points. However, Bell made one point in which I believe he was entirely right to criticize the United States. I’ll mention where I agree with him last.

Disagreement #1. According to The Space Traders, all Black People are the Same

This point isn’t secondary to the story. All black people in the United States suffer the exact same fate. The protagonist Gleason Golightly in various ways attempts to escape his fate, but in the end, being black is something he cannot escape. He is turned in and taken away, just like every other black person.

The story is just a story and is allowed to engage in hyperbole for the purpose of making a point. But I don’t think Critical Race Theorists see any hyperbole here. All black people in their view are in the same boat. Which is on the one hand ridiculous–there’s a huge difference between Oprah Winfrey and a black man who’s a fourth generation felon in maxiumum security lockup. To suggest otherwise in absolute terms is again, ridiculous.

However, there’s a tiny particle of truth here. Both Winfrey and the hypothetical felon I mentioned can be subject to worse treatment than they might otherwise receive due to racism. That much is true for both. But for Winfrey, being subject to occasional racist slights doesn’t prevent her from being a billionaire and one of the most admired people on the planet. The guy in maximum security has a different life experience.

However, my objection to the “same fate” assertion aside, my biggest beef with the idea that all black people are the same is that Gleason Golightly (hey, look at this last name for Pete’s sake) in fact is just as cynical about white people as all other black people. He just knows how to manipulate the system to his advantage better. So the story leaves no space for blacks to actually be conservative. No, if they seem different, it’s because they are working the system.

This is observed in the opening scene. The aliens speak like Ronald Reagan, which white people in the story trust, but black people don’t. All black people. There’s no room in the story for some black people to have liked Reagan–no, all are assumed to be the same. Or merely pretending to be different, like Gleason Golightly. There’s no space for individualism or individual convictions.

Note, someone could also say the story also portrays all white people as being the same, but it actually doesn’t. Jewish people are in particular set aside from other white people and the story further implies that guilt-ridden whites might actually desire to help blacks. I think that’s hugely significant and will say more about it in a bit.

Note also that Critical Race Theorists do not hold to real racial differences. They believe race is a social construct and the biological differences in race are minor–I totally agree there. But at the same time, they hold all of the United States–and broader, the whole world to a lesser degree, basically is acculturated the same way concerning race. So the unanimity of racial experience this story treats and inescapble and I think CRT in general treats race and racism as inescapable.

Disagreement #2. Racism is the Central Axis of Oppression–Nobody Would Sell Green-Eyed Redheads?

The story flat out says that nobody would have considered for one moment a request from the aliens to take, for example, green-eyed redheads. Really? Such an assertion is easily shown to be false.

Remember the post I did on Speculative Faith that talked about how early plantation owners found out African indentured servants were more profitable that Irish indentured servants? Because the Irish died at higher rates from malaria? At the end of a period of seven years service, both Irish indentured servants and African indentured servants used to be set free, with a small “gift” of land and a few tools…which didn’t cost that much for the Irish, because a lot of them didn’t live out the seven years.

Whereas for the West Africans, many of whom carry a recessive sickle cell gene that makes them resistant to malaria (one of only a few genuine biological differences in races), that got too expensive. So the plantation owners pressured the colonial legistatures to change the legal status over time, so that black people would not be set free. To protect their profits. (Then the society became increasingly racist to justify their position of dominance.)

But let’s not forget that at one point in Colonial history, a certain number of green-eyed redheads were in fact shipped to the Americas and forced to work on plantations. White people did in fact sell white people.

And not just there. Slavs sold other Slavs down the great rivers of Russia for money (some people claim the word “slave” derives from the more ancient ethnic term for the Slavic nationality). Aztecs enslaved other tribes of Central Mexico. And West Africans in positions of power helped capture other Africans–and sold them to European slave traders.

The central premise of the story, of human beings selling other human beings to gain something for themselves is something we see over and over again in the pages of history. Sadly. Tragically.

But the idea that only because of racism would someone consider such a trade–that idea is false. Easily shown to be false.

Disagreement #3, White People Will Only Help Black People from Negative Motivations

In the story, there are only two motives given for white people to help blacks. One, to not be left alone at the bottom of the social order, specifically applied to Jewish people–which might make sense in the context of the story, but does it make sense in the real world? Do Jewish people help black people with the notion that doing so will always keep black people inferior to them?

Actually, if we imagined this to be true of white people who help blacks in general, it would be subversive to CRT, or at least I think it would be. Could it really be that white people believe helping black people will keep them eternally superior, social-standing-wise, to blacks? Ugh.

Look, I have no trouble perceiving that human beings are riddled with evil motivations, but that’s some awfully dark stuff right there. If this idea were to be taken seriously, even the so-called white “allies” of black people are not to be trusted. They are really doing it for themselves.

Lest someone say I’m reading too much into the story, Derrick Bell directly said that the only time white people help black people is when “interests converge” so that white people are getting something out of it (he said so in multiple ways, but for an example, follow this link).

Hey, is it true that a lot of what human beings claim is helping others really has a lot of selfish motivations, at least most of the time? Yes. Again, I agree humans are sinners. But is it always true that the only time any white person helps blacks is for self-interested reasons? Is this particular kind of self-interest worse than all other kinds? No, it isn’t. (Or else white people would not have gone through cycles of helping and oppressing one another in Europe before the Transatlantic slave trade ever began.)

And the other motivation the story give? Guilt.

White Guilt But Not Empathy

The Space Traders doesn’t portray a single white person showing genuine empathy for black people. Rabbi Specter seems empathetic for a bit–but then his true motives of self-interest are revealed in the story.

Guilt is mentioned as something white people will experience after the fact of betraying blacks–but isn’t guilt at least somewhat related to empathy? Isn’t it possible to appeal to those white people who have suffered in life based on their hardship that black people are also suffering? Some of whom are suffering worse? All of whom who are subject to random racism?

But that’s not the argument CRT makes. Instead it talks about “white privilege” in the singular, as if all white people have the same life experience as one another. A proposition which white people who have suffered more than normal in life find especially distasteful.

Doesn’t tapping into “white guilt” seem to be the motivation behind mentioning “white privilege”? So The Space Traders and Critical Race Theory acknowledges there’s such a thing as a guilty conscience. That in spite of being sinners, we have this grace that can lead to repentence.

This is very important to undestanding Critical Race Theory in my estimation–such theorists want to help black people and other oppressed minorities. But in general, they only think white people will help them if they get hit between the eyes with their own guilt of racism.

Almost Like a Revival Meeting

Isn’t this almost like the old-fashioned Evangelical revival meeting? “You know you are a sinner! Come forth and repent, and you shall be made clean by the blood of Jesus!” And people got up and walked the aisle, thowning themselves down in repentant prayer.

“You know you are a racist! Disavow your racism and denounce those who have not yet repented! Then you can feel that you are clean!” So people come out, snarkily attacking anyone who dares question white privilege. Creating a divide, where the “repentant” develop true missionary zeal, but people who might be empathetic on racial issues become less empathetic, because they don’t believe they are especially sinful, thank you very much.

You know, I don’t want to deny individualism. I deeply believe in it. So I will not assert all white people who embrace CRT have the same motivation. Not so.

But if we are going to play the game of imputing motivations on people other than ourselves in broad, sweeping terms, such a method can make supporters of Critical Race Theory look as bad as anyone else.

A Point of Agreement

One thing The Space Traders pointed out that I agreed with and which I’d never thought of before. The story makes the observation that black people had been sacrificed for the nation before, so doing so again wasn’t unprecedented.

It specifically made mention of the US Constitution, which I also talked about in a previous post. I said in my previous post that the Constitution’s 3/5 compromise was a result of a political compromise between those who were against slavery and those who were for it. And so it was.

But The Space Traders pointed out that this compromise in effect sold out black people for the greater interests of the country. If the anti-slavery founders had been so anti-slavery, why had they not insisted on getting rid of slavery before making a federal union? Why hadn’t they refused to form a union with people dedicated to slavery?

We can say much about the history of the time, that the general expectation of many in the North was that slavery would come to an end on its own and that the Constitution actually reflects this expectation. Yes, I agree that was the common belief in the North and even some Southerners also agreed slavery would eventually end (though some disagreed with that very much). But so what?

It is actually true that anti-slavery Northerners sold out black people for the sake of making a single federal union. They compromised–in a negative way.

We could imagine things would be even worse for black people if there had been a Northern Union and a Southern Union from the beginning. But we can’t be sure about that–and it’s no excuse anyway. Yes, it really has happened in US history that black people were sacrificed for what some people considered expedient. Though not just black people–but Critical Race Theory applies to other groups as well, so there’s no disagreement here.

Conclusion

My next post will talk about some other things that I think Critical Race Theory actually has seen correctly (in addition to offering new criticisms of it). There’s actual evidence of structual inequality in America. But such inequality doesn’t quite run down racial lines like is often implied. Nonetheless, such inequality should be addressed in a society that wants to be a meritocracy–it’s not fair to make some people run a metaphorical race with weights strapped to them that others don’t have.

But that’s for next time.

As for this week’s post, who has read The Space Traders? Do you agree or disagree with my analysis? Do you know of other science fiction or speculative stories that address race in a way as meaningful (or more) than The Space Traders? Please let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

outside their characters in their narration, taking the tone of an observer of rare acuity and no inclination to cover over anything. Neither ever saw a fool without observing and declaring the fact. They are unsparing. At the same time, they draw so comprehensive a sketch of their characters that it feels a little like empathy. The fools may have been lampooned, but they were at least understood.

outside their characters in their narration, taking the tone of an observer of rare acuity and no inclination to cover over anything. Neither ever saw a fool without observing and declaring the fact. They are unsparing. At the same time, they draw so comprehensive a sketch of their characters that it feels a little like empathy. The fools may have been lampooned, but they were at least understood.

âYou wouldnât eat brownies with a little dog poop mixed in!â

âYou wouldnât eat brownies with a little dog poop mixed in!â âYou donât need to swim in the sewer to know whatâs in it.â

âYou donât need to swim in the sewer to know whatâs in it.â âGovernment agents learn to recognize counterfeit bills not by studying counterfeits, but by studying the real thing.â

âGovernment agents learn to recognize counterfeit bills not by studying counterfeits, but by studying the real thing.â

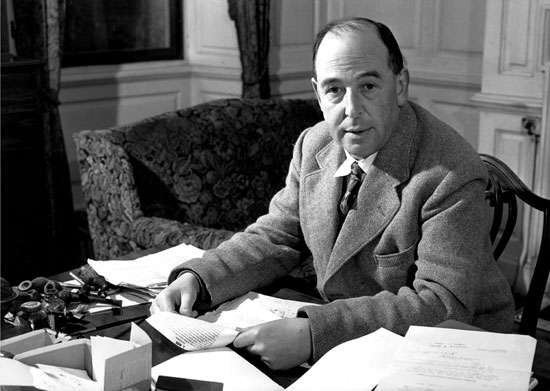

C. S. Lewis was wrong to insinuate in this story that a man who worshiped a false god could somehow also be serving the true God.

C. S. Lewis was wrong to insinuate in this story that a man who worshiped a false god could somehow also be serving the true God.

Lewis: ‘I couldn’t write in that way at all’

Lewis: ‘I couldn’t write in that way at all’ But Lewis doesn’t stop with the raw imagination

But Lewis doesn’t stop with the raw imagination

Story stage 2: ‘The Form’

Story stage 2: ‘The Form’ Story stage 3: ‘The Man’

Story stage 3: ‘The Man’

The tap, tap, tap of rain drilled into Achilusâs brain, holding him captive against sleep. He flopped over yet again, kicking the confining coverlet, and stared into the darkness. Would this reek-cursed night never end?

The tap, tap, tap of rain drilled into Achilusâs brain, holding him captive against sleep. He flopped over yet again, kicking the confining coverlet, and stared into the darkness. Would this reek-cursed night never end? An Army brat, Ronie Kendig grew up in the classic military family, with her father often TDY and her mother holding down the proverbial fort. Their family moved often, which left Ronie attending six schools by the time sheâd entered fourth grade. Her respite and âfriendsâ during this time were the characters she created.

An Army brat, Ronie Kendig grew up in the classic military family, with her father often TDY and her mother holding down the proverbial fort. Their family moved often, which left Ronie attending six schools by the time sheâd entered fourth grade. Her respite and âfriendsâ during this time were the characters she created.