I’ve done a series of posts on Speculative Faith that concluded by looking at Satanic influence in entertainment (I’m linking the last post in that series here). Of course there’s an inherent problem in even suggesting that it’s extremely common for Satan to attempt to influence the content of stories. First, it sounds like I’m minimizing human responsibility for sin, which I don’t mean to do (just because the serpent tempted doesn’t mean Adam and Eve weren’t responsible for doing wrong). Second, by pointing out where what we could call “negative influences” are laced into many stories, it may sound as if I’m rejecting creativity or denying stories can have good purposes–which I don’t mean either, not at all, or I wouldn’t be a writer and publisher. And third, so many people have freaked out about Satan in an over-the-top way that even mentioning the Devil causes some people’s eyes to start rolling around, assuming nothing but a paranoid rant follows (and mentioning Satan causes some other people to freak out and overreact). Neither a rant nor freaking out is what I have in mind.

So perhaps when talking about looking at negative influences in stories, to be better received, it would be more to my advantage to avoid using words like “Satan” or “evil” or even “a potential for evil,” at least for now. Though please do understand that I believe it’s not an accident that so many “negative influences” are in a great many stories. In that light, this post is a case study in looking at negative influences based on two stories, the G-rated tale, Frozen. And the R-rated movie, Grand Torino. Hint: I don’t see the rating as a strong indicator of whether a story is clear of negative influences or not.

Are G-ratings automatically good?

I’ve already telegraphed that my answer to this question is, “No.” But why? Doesn’t a G-rating guarantee a story doesn’t have content that won’t traumatize a child? Doesn’t clean, family-friendly fiction equal good?

I think Bambi was traumatic for lots of kids, by the way. However, Bambi was not a primary example I picked for this post. My point in mentioning it is yes, G-ratings are generally geared towards making sure a child isn’t exposed to trauma, but there have still been traumatic G-ratings. And also–G-rated films at times have had powerful impacts on public opinion, as a linked article about wildlife conservation discusses the effects of G-rated movies on attitudes about animals.

So if Bambi and other G-rated movies can change people’s attitudes about animals (Finding Nemo made the clownfish an extremely popular aquarium tank addition, for example), could it be a G-rated film would have influence towards sin, even if it doesn’t necessarily show sin “on camera”? Just as the death of Bambi’s mother didn’t happen on camera but still was a powerful part of the story?

Yeah, I’m saying G-rated films can have a negative influence.

But don’t you like clean fiction?

Last week’s post included me mentioning I like the Netflix series The Kingdom and that I also find it relatively clean (no nudity, no profanity, even though it it is at times quite graphically violent). The fact I mentioned “clean” as a virtue would seem to indicate I hold clean fiction up as a good thing and graphic fiction as bad.

In fact, it’s an extremely common attitude among Christians to see G-rated “clean” as good and R-rated as bad. Though it’s getting to be a rather old-fashioned attitude now.

More common now, at least in the circles of friends I have, is to think profanity amounts to just words that only have the meaning people assign to them (as opposed to being intrinsically bad), so they mean nothing, so they are just fine in fiction. Acceptance of nudity in film is less common, but some people do accept it de facto by watching, say, Game of Thrones. And some few people accept nudity in media more openly as being only natural or not much of a big deal or “something I don’t like, but it doesn’t affect me much.”

So where am I on the spectrum of G to R? I’d say I’m not really on that spectrum at all, because there are G-rated films I don’t care for and R-rated media I think are generally good. Though I do think R-ratings are in general more prone to showing content a Christian should reasonably object to. Here’s why I say so:

On “normalizing”

In general, if you expose someone to something in a story enough times, a person comes to see what they observe in a tale as normal. Whereas a story may attempt to portray something as abnormal or show something bad with the intent of showing it being bad, in general, people identify with the protagonists of a story. If the protagonist does something, people think what the protagonist does is good and normal. Generally.

This is one of the primary ways that stories influence people. Sure, it isn’t the only way, but in general, if a story shows the central figure of a story doing something, it’s promoting the audience doing and thinking the same thing. Again, of course it is possible for a viewer to see the protagonist as aberrant and not identify with him or her. But generally a reader or viewer will have no interest in a story in which they have nothing in common with the main character. Again, generally.

So what do I think about some of the main behaviors R-rated movies are known for normalizing?

On profanity

Yes, it really is true that words only have the meaning a culture assigns to them. Which means in terms of meaning attached to sounds, “duck” isn’t any dirtier a sound if you start it with the letter “f” than if you start it with a “d.” So what? A word isn’t just a sound, it’s a meaning attached to a sound. And we live in a culture in which mostly comedians but other folks as well systematically used many of the most offensive words they could in order to shock people into laughing. Or reacting.

Now it’s become a cultural habit for many people to routinely use the most shocking terms available to them out of a menu of all possible terms. Yeah, since it’s become cultural, a lot of these terms have lost a lot of their shock value and in effect are becoming less vulgar than they used to be. And due to shifting cultural attitudes, some other terms are more vulgar than they used to be, like racial slurs. (But certain comedians use racial slurs, and in general comedy seems to keep using whatever terms are most shocking, so this is an ongoing issue…)

Still, it’s the very act of seeking the strongest language possible that’s objectionable. Why should Christians be cool with that? Don’t we believe our mouths belong to Christ? So I think in general Christians should be against profanity.

Though we should also recognize not everyone uses “bad language” with the same intent. For some people, it’s just a habit they picked up from others. We don’t have to act offended and holier-than-thou when talking with such people. But we don’t have to imitate them, either!

So in general I prefer media in which the main characters don’t cuss. However, I also like media in which people deal with adult issues like death, suffering, violence, and hardship. And it’s quite challenging to find media that deal with adult issues without using “adult language” (which could be better called “shocking language”). So sometimes I accept profanity in media I consume, even though I don’t want to produce profanity in what I write or publish. Because it’s just not necessary to use the worst words available for emphasis.

By the way, to anyone who would think that cussing is only normal if the situation is tough enough, I’d say yeah, that’s a little true in that people who would not otherwise swear are more likely to do so when things go bad. But I’ve generally avoided using profanity in my life, even when surrounded by it in the military. Though I did use the four letter word referring to excrement when getting rocketed in Iraq. Which I suspect had more impact when I said it because I normally don’t use that word. But anyway…

On nudity and violence

Look, some stories refer to nudity because it’s important to the story. Nazis really did strip down death camp victims before sending them to be gassed in the showers. But most stories don’t need it at all and those that include it don’t need to play up the sexiest aspects. Even if one character is seducing another, it’s not necessary to show everything.

Plus I have a problem in which I can’t look at the body of a healthy nude woman without feeling some desire. I think my problem is a pretty common one, but not many people I know openly mention they have an issue. So in general I’m against the normalization of nudity in visual media.

Violence I am more accepting of–but that’s in part because I find violence repulsive and not attractive. I don’t like gore or bloodshed. Though I can’t say I am not drawn to the shock value of violence at times, moved by the portrayal of violence at times. As in Saving Private Ryan or The Passion of the Christ and many other examples.

Though I think normalizing gore, as in getting people used to seeing it so that they are not shocked by it, is a negative effect. So I would prefer violence to be suggestive rather than realistic in most cases, though there are exceptions.

So aren’t you contradicting yourself? (Or, on bad behavior.)

No, not really. In general, I find stuff that tags a movie or other media with an R-rating is not necessary. But there are exceptions. The thing I’m most concerned about is effects on me. My own potential for bad behavior.

I don’t want to be exposed to so much profanity with the purpose of being shocking or funny (yes, I’m talking about you, Deadpool) that I use it without thinking. Because I don’t want to use the most offensive language possible to me–that’s rude at the very least.

I don’t want to be exposed to nudity that causes me to lust. Nor do I want to see so much nudity that I think nudity is simply normal and I have no sensitivity to it anymore. But I don’t see nudity as absolutely forbidden in stories.

I want to see violence that shocks me and makes me feel the stakes are high, i.e. landing on Omaha Beach in Saving Private Ryan. I don’t want to see so much violence I no longer care about it. Nor do I want to see a celebration of violence as funny or somehow cool.

So let’s get to the comparison: Frozen and Gran Torino.

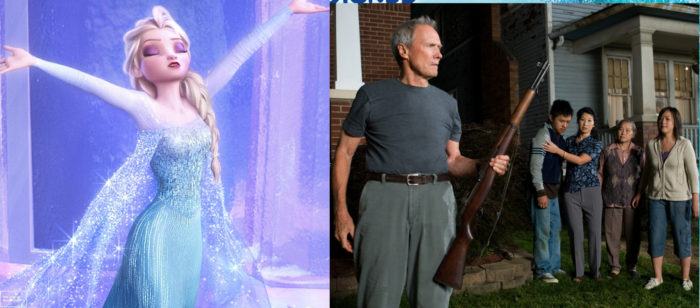

Gran Torino main cast. Image copyright: Warner Brothers.

Image copyright: Disney

Readers, most of you have probably deduced by now that I’m going to say I think Frozen is a worse movie that Gran Torino. Yep, that’s what I think. (By the way, I’m going to assume you are familiar with these films without explaining them–if you’d like to look them up on Wikipedia to find out more, feel free to do so.)

Gran Torino

Note my general approval of this Clint Eastwood film in spite of me having some real reservations about Gran Torino. Not only does it do a lot of normalizing of profanity, it also includes a lot of racial slurs. A lot. Which I definitely don’t think are good and don’t habitually want to pick up. Though we can fairly say that the movie also goes out of its way to show the protagonist, Walt, is habitually profane and doesn’t necessarily mean it the way other people would.

The movie was also both praised for including real Hmong people as actors and condemned by some for including certain stereotypes, including getting some common characteristics of Hmong culture wrong (most importantly perhaps, that Sue is raped by a gang that would be part of her clan, which would be as much anathema to Hmong culture as to anybody else). So we ought to accept the limitations of what the movie shows about Hmong.

We could also say the movie perpetuates stereotypes of tough guys (“toxic masculinity” someone might say) as heroes. But I would say that the film shows a real downside to Walt’s masculine perspective on the world, including alienation from his family (never being able to connect with his sons). In some ways, he expresses himself more to his neighbor Than than he had done for decades prior. Which we can see as a thawing of typical male “toxicity.” (Note I am not saying I see something inherently wrong with being masculine–I don’t think that way. But there’s a point in going too far, especially in not expressing emotions.)

The film has also been criticized as not being sufficiently subtle or nuanced. Yeah, there are more nuanced films. But lack of nuance makes it easier to use here as an example.

Another complaint about this film is that a white person helps a non-white person. “White savior” is what that’s called. Honestly, this gets my eyes rolling–what, it would be better if he were an apathetic white person? But I can actually concede the point that while Than (Spider) and Sue are very important characters to the film, they are in some ways portrayed as lacking the ability to resolve their own problems or “lacking agency.”

Overall, it can be fairly said this movie has a message pointed at a white audience more than an Asian one. Ok, fine. But what is that message?

The film on the positive end of things includes:

- Someone who seems more racist than he is (but who really is racist) developing compassion and empathy for people of another race.

- The protagonist shifts from being hostile to his neighbors to loving his neighbor as himself.

- The protagonist literally dies to save the life of his neighbor. In fact, when he’s shot dead by the Hmong gang, he even opens his arms wide, his supine corpse forming the shape of a cross.

Walt’s death. Image copyright: Waner Bros.

- The death of the protagonist buys freedom, i.e. salvation for the secondary character of Than.

In short, the essential theme of Gran Torino is self-sacrificing love. A very Christian view of that kind of love, including a nod at substitutionary atonement. Even though it has other characteristics we should admit to and confront and not celebrate.

So what’s wrong with Frozen?

Just as I conceded bad things about Gran Torino, let’s admit good things about Frozen. The film is clean of course, which means it doesn’t normalize racial slurs or profanity. That’s a good thing.

Also, the movie does a course correction on the general “love at first sight” thing that Disney princess movies have way over-done. (Is “love at first sight” an actual thing? Ask around and you will find out it is–but is it the only way people get married and come to know each other? Not even close!) By casting Hans as a bad guy, we can say Frozen does provides an important on-the-other-hand to older Disney films.

And we can in addition celebrate that the climax of the story features Anna sacrificing herself to save Elsa and everything turning out well as a result. Isn’t Frozen the same as Gran Torino, each a story about self-sacrificing love? Um, no, I wouldn’t say they are the same, even though there is some similarity at that point. Not even in the self-sacrifice part. It isn’t the same because Anna doesn’t actually die, but only appears to. And sacrificing for a close relative is the most common kind of self-sacrifice in the real world–it’s much more powerful (I would say) to self-sacrifice for someone you are not related to.

But more importantly, the hit song that everyone remembers from Frozen is not about self-sacrificing love. Anna’s love for Elsa and vice versa are very important to the story to be sure, but something else, another idea, is more important to the story and more memorable. Let it go.

So Elsa’s parents tell her in essence to control an aspect of herself in order to prevent harm to other people. And even have her cover up with gloves and such. Eventually, Elsa realizes she can’t cover up and can’t be what her parents want: she has to “let it go!”

What’s wrong with letting it go?

The story of course is G-rated, the closest it gets to tying letting “it” go to sexuality is Elsa takes off the extra clothing and gloves her parents say she needed to wear. Though I rather suspect many people will wind up subconsciously linking the “it” of “letting it go” to sexual behavior at some point. Because people think about sex, people. Honest!

Oh, I’m being a dirty-minded prude, am I? That’s what some people are thinking on reading this.

Ok, lemmie admit that the “let it go” thing is very general overall, with only a few hints like clothing that point in the direction of sensuality. It could well be someone could see this film and never, ever pick up on what I’m talking about. Though just because that’s possible, that doesn’t mean most people would never subconsciously pick up a connection–but anyway, it doesn’t really matter. The point doesn’t change much if “let it go” has a general reference.

“Let it go” could be applied to anything. Even good things. Maybe you’ve been suppressing an artistic talent and you need to “let it go.”

But does our society in general have a problem with being too suppressed, too under control? Does our society as an overall whole need to let things go more often? Eh, I’d say, “No.”

Doesn’t fighting against sin in general in a Christian’s life include suppressing things you know you shouldn’t do? Yeah, a Christian should “walk by the Spirit” which includes the Spirit guiding a person to do good things from an inner motivation. But what if at any given moment you don’t want to do good? Is it in general OK to “let it go?”

Um, pretty much, no.

The overall impact of “let it go” might be different if it went to Victorians. Arguably, they were too repressed and needed to relax at least somewhat (ironically, maybe Walt in Gran Torino could “let it go” a bit). But is that what our culture needs? This reminds me of what C.S. Lewis had his demon offer up as advice in The Screwtape Letters:

“The use of fashions in thought is to distract men from their real dangers. We direct the fashionable outcry of each generation against those vices of which it is in the least danger, and fix its approval on the virtue that is nearest the vice which we are trying to make endemic. The game is to have them all running around with fire extinguishers whenever there’s a flood; and all crowding to that side of the boat which is already nearly gone under.”

Yeah, I don’t think “let it go” is a good message for our culture. Yes, I think it’s subversive overall. Even though it could be applied to good things.

So are you saying we should ban Frozen now?

No. Not at all. First of all, negative messages are very common in stories. Including some G-rated films. Banning them all doesn’t even make sense. If you don’t want to watch a particular show because you think it’s bad, that’s fine. But protesting to Disney or getting angry I think is a waste of time.

As a creator, if I don’t like that kind of story, my most logical option is to attempt to make one I think is better–though there is no guarantee I will be able to do so in terms of quality and production. It fact, beating the appeal of Disney is awfully hard. (That doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try!)

Confront the negative, emphasize the positive

What I am saying we should do is admit the troubling aspects of calling out in general to this society to “let it go.” If our kids see Frozen, we should talk about the issue of whether Elsa really did have to let it go. Were her parents wrong to ask her to do that in the first place? Was there perhaps another solution available to them? What if the impulse Elsa was fighting was to steal from people? Or murder people? Would it be OK for her to “let it go” then? When is it and is it not OK to “let it go?”

You can also talk about positive way to see “letting it go”–maybe you could deliberately link it to creativity. Or honesty.

You could alternatively say (especially if talking to other people’s kids, when you don’t have as much freedom) what you really like about the story is Anna’s self-sacrifice for the sake of love, but that the other part of the story you didn’t like as much.

There are in fact lots of ways to react. But I think confronting the negative or potential negative is a part of a healthy reaction. If you aren’t doing that, you aren’t really dealing with the world we actually live in. A world in which, yes, it really is true that an evil spiritual mastermind is trying to influence our culture.

We don’t have to freak out–we don’t have to ban things–we don’t have to over-react. But we should admit real issues, confront them, and also accentuate what is good.

Ask yourself this, did Jesus ever confront wrong attitudes in people–He actually did. Often. Though not by rejecting supposedly bad people outright.

We can do the same.

Be sober, be vigilant

What I’m talking about is all part of walking a spiritual walk. Like good soldiers (2 Timothy 2:3), we endure the difficulties of life, we prepare ourselves by putting on the armor of God (Ephesians 6:10-18), and we remain alert to what the enemy can do (I Peter 5:8), confident in our weapons being able to face anything thrown our way, but alert to something taking us by surprise. Which means we can in fact enjoy things around us, but we have to enjoy with a weapon strapped to our hip, so to speak. Our guard should never go all the way down. Not even for G-rated movies.

Don’t judge a film by its rating as much as what messages it contains–not that ratings don’t ever matter.

So, dear readers, what are your thoughts on this topic? I’m perfectly fine with you disagreeing if you wish. I’d like to hear your point of view!

(By the way, I’ve recorded a version of this post to a podcast–one where I covered the same material in different words:)

https://travissbigidea.podbean.com/e/it-s-not-in-the-rating-looking-at-negative-influences-in-stories-frozen-and-grand-torino/

Notice, Churchill was not saying, it’ll all be over soon and we can get back to being comfortable and living in ease. He held up one hope: survival. And to achieve that, he asked his people for blood, sweat, toil, and tears.

Notice, Churchill was not saying, it’ll all be over soon and we can get back to being comfortable and living in ease. He held up one hope: survival. And to achieve that, he asked his people for blood, sweat, toil, and tears.After evacuating the Capitol earlier in the day, roughly 150 Members of Congress came together in the evening on the building’s East Front steps to convey the resolve of the nation during a time of great tragedy. Senators stood by Representatives, Democrats next to Republicans, and the leadership of both houses gathered as a symbol of strength for a country shocked and saddened by the day’s barbaric acts of terrorism. Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert of Illinois addressed the Nation . . . After Members observed a moment of silence over the dayâs tragedies, those assembled broke into an impromptu rendition of âGod Bless America.â

In turn those alien creatures attacked the vessel. Enter Voyager, not knowing why the other Star Fleet ship was enduring these repeated attacks. As the story unfolds, including the kidnapping of one of the Voyager crew and the removal of the Doctor’s ethical subroutines (he’s a hologram), Janeway at last learns of the ways the other captain has ignored his Star Fleet oaths and abandoned the ethics which govern the organization.

In turn those alien creatures attacked the vessel. Enter Voyager, not knowing why the other Star Fleet ship was enduring these repeated attacks. As the story unfolds, including the kidnapping of one of the Voyager crew and the removal of the Doctor’s ethical subroutines (he’s a hologram), Janeway at last learns of the ways the other captain has ignored his Star Fleet oaths and abandoned the ethics which govern the organization.

Satan’s plan was to bring Job to the place his wife tempted him to go: “Curse God and die.” He wanted Job to be an example of a person who only worshiped God when things were going well. As soon as life was unbearable, Satan reasoned, Job would turn against God.

Satan’s plan was to bring Job to the place his wife tempted him to go: “Curse God and die.” He wanted Job to be an example of a person who only worshiped God when things were going well. As soon as life was unbearable, Satan reasoned, Job would turn against God.