C. S. Lewis Fifty Years Later

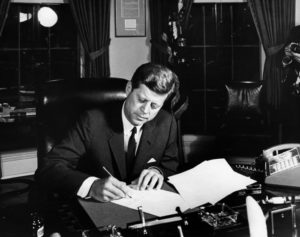

This week the media began their expected tribute to President John F. Kennedy who was assassinated November 22, 1963. Two other famous men died that same day–both writers. The one was Aldous Huxley and the other, C. S. Lewis.

This week the media began their expected tribute to President John F. Kennedy who was assassinated November 22, 1963. Two other famous men died that same day–both writers. The one was Aldous Huxley and the other, C. S. Lewis.

I’ve asked the question over the years, which of the three will history remember as having had the greater impact? Of course, that’s the kind of thing no one can truly quantify. But as much talk as there is this week about President Kennedy and how “everything changed” after he was killed, I don’t recall a great deal of discussion about his ideas or influence over the past ten years. Some.

Often politicians invoke President Kennedy’s memory as part of their election campaigns and the media will mention “Camelot” in wistful tones or Marilyn Monroe’s birthday song to him with knowing winks. And of course there are the conspiracy theory discussions. But President Kennedy’s influence?

Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, has fostered even less discussion though his dystopian fiction fits in quite nicely with the high profile young adult dystopians of the past few years. He also embraced such ideas as Universalism, pacifism, mysticism, and “Vivekananda’s Neo-Vedanta” or Neo-Hinduism which has seeped into mainline western thought.

Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, has fostered even less discussion though his dystopian fiction fits in quite nicely with the high profile young adult dystopians of the past few years. He also embraced such ideas as Universalism, pacifism, mysticism, and “Vivekananda’s Neo-Vedanta” or Neo-Hinduism which has seeped into mainline western thought.

I certainly don’t want to take anything away from the impact that President Kennedy or Aldous Huxley had, but C. S. Lewis’s legacy seems to grow year after year.

Though the subject of their admiration was, among other things, an Oxford scholar, a literary critic, a poet, a writer of more than 30 books and countless shorter pieces and speeches, a war veteran, and even a broadcaster, to many it is Lewis’ contributions as a masterful Christian apologist that most endears him to readers and endures a half-century after his death. He made the complex simple and the brain-bending breezy. An estimated 200 million copies of his books are in print, and today they continue to sell about 2 million copies annually. (“C.S. Lewis: Even 50 years after death, his work deeply inspires,” Christian Science Monitor, emphasis added)

Chicago Tribune columnist Cal Thomas has weighed in on the question, and he sizes up the influence of these men the same way I do:

Of the three, it was Lewis who not only was the most influential of his time, but whose reach extends to these times and likely beyond. His many books continue to sell and the number of people whose lives have been changed by his writing expands each year. (“Kennedy, Huxley and Lewis”)

Certainly the Narnia movies, though a disappointment to true C. S. Lewis fans, sparked a renewed interest in Lewis’s fiction, but his reputation has never stood upon his storytelling alone. I personally have loved his fiction most, but I appreciate his non-fiction greatly.

Certainly the Narnia movies, though a disappointment to true C. S. Lewis fans, sparked a renewed interest in Lewis’s fiction, but his reputation has never stood upon his storytelling alone. I personally have loved his fiction most, but I appreciate his non-fiction greatly.

Of his works, my favorites are Till We Have Faces; The Great Divorce; The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; The Last Battle; Screwtape Letters; Surprised by Joy. Of those, only the last is non-fiction.

By today’s style of writing, Lewis’s fiction fails miserably. He writes in the omniscient point of view, uses far too many adverbs, and tells more than he shows. Yet his stories resonate with truth, and consequently they stick. In fact, for me, they have revolutionized my understanding.

I came to see my relationship with God in a different way after reading about Aslan and his relationship with the kings and queens of Narnia. I grasped the reality of heaven like I never had before after reading The Great Divorce, and I recognized the way temptation draws me away from God upon reading The Screwtape Letters. Mostly I apprehended to a greater degree God’s love and sacrifice and demand for our surrender to His way.

And of course, Lewis showed me what a writer could do with fiction. He made me want to put truth in stories so that readers would grasp profound realities because of a simple line (E.g., the overly used but nonetheless profound quote from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe: “Safe?” said Mr. Beaver […] “Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.” [excerpt from Ch. 8: “What Happened after Dinner”]).

Noted scholar Clyde Kilby concluded his book Images of Salvation in the Fiction of C. S. Lewis with an insightful observation about the truth Lewis made pivotal in his stories:

throughout all of Lewis’s Christian works we find a great difference in eyesight–or better, spirit-sight–between the saved and the unsaved. How very blind poor Orual was, and that for most of a lifetime. How well Psyche saw, even from early childhood. How clearly Lucy Pevensie saw always, and how blind was her sister Susan, even in the very presence of Aslan. How blind were all but one of the passengers on the bus from hell to heaven. How eternally clear sighted was the Green Lady and how myopic Weston. How often blind are the so-called great in any age and how seeing the humble and quiet of spirit. Lewis’s insight into this difference between sight and blindness is no less explicit than that presented in the Bible itself.

Even his poetry is filled with these themes. Here’s a sonnet of his centered on this truth:

The Bible says Sennacherib’s campaign was spoiled

By angels: in Herodotus it says, by mice–

Innumerably nibbling all one night they toiled

To eat his bowstrings piecemeal as warm wind eats ice.But muscular archangels, I suggest, employed

Seven little jaws at labour on each slender string,

And by their aid, weak masters though they be, destroyed

The smiling-lipped Assyrian, cruel-bearded king.No stranger that omnipotence should choose to need

Small helps than great–no stranger if His action lingers

Till men have prayed, and suffers their weak prayers indeed

To move as very muscles His delaying fingers,Who, in His longanimity and love for our

Small dignities, enfeebles, for a time, His power.(from Poems, C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper)

Just for fun quiz:

1. Which of Lewis’s books did he dedicate to J. R. R. Tolkien?

2. To whom was Screwtape writing?

3. Which of Lewis’s books is his spiritual autobiography?

4. In the quote above from Dr. Kilby, he points out Lewis’s use of sight as a metaphor for spiritual understanding. Name at least one other character besides Susan from the Narnia books who suffers from blindness to Aslan’s reality.

5. How different do you think Lewis’s fiction would be if he had never become a Christian?

Feel free to leave your answers in the comments below. 😉

What impact has C. S. Lewis had on you as a reader or as a writer? Are you more familiar with his fiction or nonfiction? Which books are your favorites? Have you read his poetry?

Wonderful article, Becky! This was a great tribute, and the quiz at the end is a fun idea! My answers:

1. Out of the Silent Planet–I’m pretty sure about this without looking it up. (And I read somewhere that Dr. Elwin Ransom was modeled after Tolkien).

2. I should know this (loved The Screwtape Letters), but I don’t. 🙂

3. Surprised by Joy (I think).

4. Uncle Andrew from The Magicians Nephew; Trumpkin the Dwarf from Prince Caspian; Bree the Horse (at first) from The Horse and His Boy. Interesting that Edmund in LWW was never blind to Aslan’s reality–he hated it instead.

5. Drastically different is the short answer. He probably would have come from a very atheistic worldview, yet tried to show beauty somehow, except such beauty would be obviously imperfect or at odds with his worldview.

Lewis’s impact on me? His Narnia books inspired me to be a writer in the first place. 🙂 I’m more familiar with his fiction, but I want to read his non-fiction (help! Someone find me time!), and I’ve read a portion from Queen of Drum. I can’t pick a favorite. It’s like picking a favorite sibling.

Blessings

~Literaturelady

Thanks, LL, it was a lot of fun to do. I have so much respect for Lewis. He was a great thinker and has indeed influenced so many of us, so it’s a joy to put the spotlight on him.

Becky

I wouldn’t call a style like Lewis’s a “fail,” much less “miserably.” Unless that’s meant to be facetious. With today’s dumbed-down destruction of style, particularly in Christian circles, where we want everyone to write the same things the same way, Lewis remains as individual in his stylistic expression as he must have been in life.

It’s interesting to compare Lewis’s style to Tolkien’s–Lewis’s is much closer to what writers use today, while most Tolkien imitators get bogged down in strands of purple prose.

Interesting thoughts, Julie. As I said to HG, though, I don’t think Lewis is writing much like contemporary writers either. But no doubt, Tolkien and Lewis were very different from each other. That would be an interesting study! 😉

Becky

H. G., I was thinking primarily of two things when I said “fail miserably” in regards to his style. First, I question whether any publisher would have picked up his stories. I mean, some defy pigeonholing into an established genre. Where would you shelve The Great Divorce, for example? But also, I was thinking about sales. Readers today know C. S. Lewis is great, so they will be patient with a style that is unfamiliar or out of the ordinary. But if he had no reputation and did manage to get in print, how many people would read Out of the Silent Planet instead of Star Wars?

In other words, I’m speculating that C. S. Lewis, writing in a style of a previous era, would not have been well received if he were just starting out today. I think there’s even some movement against him today. As I researched, I found one person who said Lewis was a great storyteller but not a great novelist. I think that’s a reflection of the change in our expectations for novels (faster paced and structured in a manner similar to screenplays), and according to these new standards, Lewis doesn’t measure up like most contemporary writers do. He doesn’t create sexual tension or carry the reader from one near catastrophe to another without a chance to catch his breath.

In short, his fiction is unique, insightful, and truthful, but if he were just coming onto the stage today, I doubt if he’d have a hearing.

Becky

1.Which of Lewis’s books did he dedicate to J. R. R. Tolkien?

I’m pretty sure it was That Hidieus Strength–which is ironic, as Tolkien hated the mixture of mythology.

2. To whom was Screwtape writing?

His nephew Wormwood,

3. Which of Lewis’s books is his spiritual autobiography?

Surprised by Joy

4. In the quote above from Dr. Kilby, he points out Lewis’s use of sight as a metaphor for spiritual understanding. Name at least one other character besides Susan from the Narnia books who suffers from blindness to Aslan’s reality.

The Black Dwarves in the Last Battle

5. How different do you think Lewis’s fiction would be if he had never become a Christian?

Would he even have written fantasy without become a Christian?

And he’s being honored with a memorial in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey. About time, too. In fact, it’s being installed this week. A great week for 50th anniversaries in speculative works–Doctor Who turns 50 on the 23rd!

Julie, I’m glad you mentioned the memorial that’s going up for Lewis this week in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey. I think it shows that he has been accepted in literary circles has having staying power. He is a lasting influence, and I’m really happy he’s receiving this kind of acknowledgment.

Becky

Well, if that’s what his poetry is like, I’m kinda glad I haven’t read it. That’s some anemic rhyming, and I’m not particularly impressed with his descriptors.

Notleia, I think I like Lewis’s poetry because I can pretty much always figure out what he’s saying! There’s a lot of poetry that loses me.

His strength may not be in his rhymes, but I think his allusions are wonderful.

He himself didn’t think he was a very good poet–I think he said something like that in Miracles. I think poetry is really hard to write, so I admire anyone who can do it and make sense.

Here’s one of his I like:

Becky

I like poetry that is reasonably accessible but still deep and evocative. I’m not a fan of too-obvious rhyme schemes and metrical patterns. The pleasure comes either from finally recognizing a pattern where you thought there was only randomness, or else from seeing a surprising exception in an obvious pattern that reveals the pattern to be more complicated than you thought.

If I may promote a Christian speculative writer, G.L. Francis from the Anomaly forum sent me her poetry collection Under Every Moon to review, and I think its an interesting read.

I tend to think that if Lewis had never become a Christian, he may never have written fiction at all. Non-fiction almost definitely, but stories, especially stories for children, I just don’t see.

That’s a great answer, Ashlee. You just might be right. He would probably have written nonfiction and maybe poetry, because he was a man of letters, but I don’t know if he would have tried fiction. All his stories are so tied with his faith, it makes you think he wouldn’t have had anything to say without his Christianity.

But as I write this, it makes me think how much I want my fiction also to be so tied to my faith that the two can hardly be separated.

Becky

He did write at least one short story before he became a Christian. I haven’t read it – only read about it – and I can’t remember its name, but it was about a blind man who is cured and wants people to show him what ‘light’ is.

Some of his poems are better:

“Have you not seen that in our day

of any whose story, song or art

delights us our sincerest praise means,

when all’s said, you break my heart?”

I actually have the whole book of his poems, and some of them are beautiful. It may be clumsy by modern standards, and he’s not primarily a poet, but he definitely has some clever points.

I like the idea expressed, but I think the phrasing is awkward and the rhyme is blah (but yay for a consistent meter? I dunno). But I don’t think it’s clumsy just by modern standards. There are probably a list of names I could drop who I consider to be better and who were also dead by the time Lewis was born (yay for majoring in English).

But poetry is probably more subjective than prose, and I’ll admit bias because I really dislike blah rhymes.

I guess I’m not understanding what you mean by “blah rhymes.” I can’t write poetry because when I use rhymes, they are forced and/or change the intent of my thoughts. I think some people “cheat” by using near rhyme or by using a clipped form of a word. I didn’t see Lewis do any of that in his “Sonnet.” Maybe you can elaborate what you mean, Notleia.

Becky

Bainespal called them too-obvious rhymes, which is essentially what I was going for. “Art” and “heart” and “our” and “power.” Then again, I’d probably be able to overlook it if the phrasing was snappier or the imagery better or something, like TS Eliot’s “I grow old…I grow old…/I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.” I don’t know why, but that couplet really sticks with me. It conjures up images of those old, short widowers who never learned to sew and instead roll up their pants legs to avoid tripping over the extra length. One old guy I knew stapled his instead of hemming them.

You’re right, Julie, he’s not a poet really. He was a scholar who wrote poetry. And maybe for that very reason I like his poetry. I can relate to not being a poet! 😉

Becky

“How different do you think Lewis’s fiction would be if he had never become a Christian?”

I heard that he already was a fiction writer before he became a Christian, and after he became a Christian it was not until he read George MacDonald’s fantasy called Phantastes that, as he put it, his imagination was baptized (I have read Phantastes too, and I recommend it).

Without his Christianity his fiction probably would have been cheap, offensive, early examples of Science Fiction.

“What impact has C. S. Lewis had on you as a reader or as a writer?”

I love how unique his ideas are, for example, a white witch in the form of a queen.

It powerfully inspires creativity to think about his stories.

“Are you more familiar with his fiction or nonfiction?”

The fiction: mainly the Chronicles of Narnia.

The movies are parasitic, but would be marvelous if they had thought of them themselves.

“Which books are your favorites?”

Probably my favorite is The Dark Tower in his unfinished works: after reading that I felt as if a firework had gone off in my head: I could smell the sulfur.

Of the Chronicles my favorites would be The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, Prince Caspian, and The Magician’s Nephew, in that order, greatest to least.

Of the Space Trilogy my favorite was the middle book, Perelandra.

I loved the idea of the flying casket.

“Have you read his poetry?”

His poetry interests me, as until now I had only seen the short rhymes in The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe.

His thoughts are good, though his structure, and the line breaks in the middle of clauses, knock me off balance.

My favorite line is:

“Lord of the narrow gate and the needle’s eye”

The BBC is full of stuff about CS Lewis just now. Particularly the radio. The Screwtape Letters is the Book of the Week this week. A radio dramatisation of Shadowlands, a program about his Northern Irish childhood…

Here they are:http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/search?q=cs%20lewis – (you may not be able to listen to them all outwith the UK)

My answer as to his spiritual autobiography would be “The Pilgrim’s Regress,” not “Surprised by Joy,” but I think either would work.